by Martin Butler

Diversity is all the rage. It has even reached the boardrooms of the UK’s top companies and indeed those that are not so top. Targets are set for the percentage of women and ethnic minorities who should populate these boardrooms. A group known as the 30% Club aims for “30% representation of women on all FTSE 350 boards” and “to include one person of colour”.[1] We are told that although we have some way to go, things are moving in the right direction. This all seems very progressive and few voices, even from the more conservative corners of the business world, object. But there’s something odd about this. Why has an idea about boardroom composition that would further the interests of a diverse population to a far greater extent (and which has been around in the UK since the 1970s) been implacably opposed by the business world? What is even more puzzling is that, far from finding the wholesale acceptance achieved by the aims of the 30% Club, this idea has been rejected out of hand without shame or negative publicity. The idea is that boardrooms ought to incorporate an element of democracy, that employees in a company ought to have at least one elected representative on the board of directors who can advocate for their interests. There is no club to promote a modicum of democracy in UK boardrooms, and there is no pressure for one either.[2]

In the UK, the Bullock Report of 1977 recommended a system of worker directors on the boards of large companies, an idea to those of my generation which seemed as compelling as the idea that boardrooms should be ‘diverse’ is to today’s generation.[3] Of course this report was never implemented, and the coming Thatcher years saw the rise of the neoliberal ideal that the prime purpose of any public company was the ‘maximization of shareholder value’ (known as the Friedman doctrine after the economist Milton Friedman[4]). This excludes any room for boardroom democracy. Over the last two decades there has been talk of a company’s ‘stakeholders’ – in other words, all those with an interest in the success of a company (not just shareholders) – but no mechanism has been introduced that might actually rebalance the scales in favour of the ordinary employee. Short term profits and shareholder value reign supreme. Teresa May timidly suggested introducing some kind of worker representation on the steps of Downing Street after the 2017 election, but again this idea was quickly buried by the powerful business lobby. The experience of the last 50 years seems to be that if companies can get away with low pay and degraded working conditions, by and large they will, which is why the Labour government needed to imposed a minimum wage in 1998. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Temple Wall Philosophy. Galle, Sri Lanka, 2010.

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these.

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these. Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

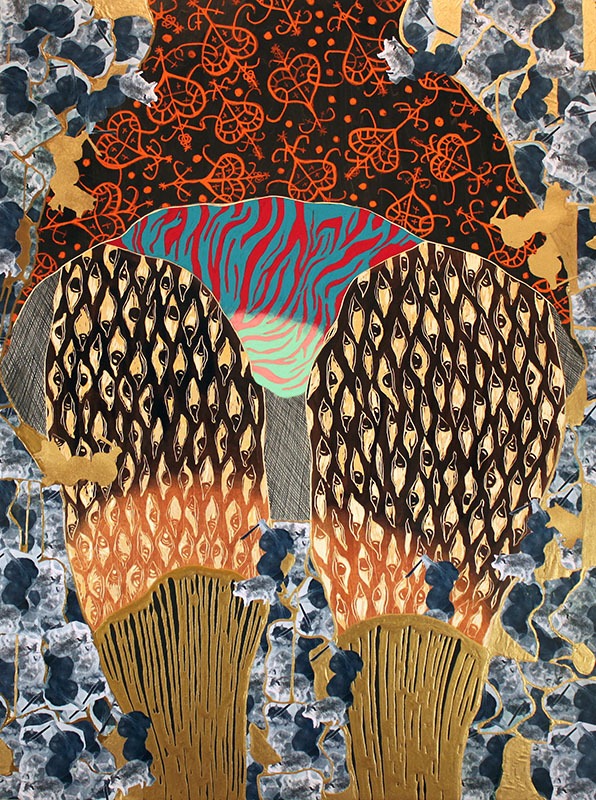

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”