by David J. Lobina

And now, by popular demand – that is, on account of the few people who wrote in the comments section of last month’s post – here’s an expanded endnote 4, which in the alluded post was meant to answer one simple question but in the event did no such thing. Namely: What on earth has happened in Catalonia in the last ten or so years?[1]

It all started in Arenys de Munt, a town of about 9,000 people 40 kms north-east of Barcelona. I’m kidding, but only in part. In September 2009, Arenys de Munt held a referendum of independence, which according to the journalist Guillem Martínez, my guide in this post, was the first case of an explicitly secessionist vote in Catalonia in modern times, and the perspective that would dominate what is now known as the procés [“process”].[2] In fact, there were a number of such consultations in different areas of Catalonia between 2009 and 2011, all of which should be regarded as independentist exercises rather than independence referenda, as participation was generally low and support for independence unnaturally high – the turnout in a vote in Barcelona in 2011 was only 21%, with 90% of voters supporting independence. As mentioned last month, numerous official surveys of Catalans show that support for independence is not the majority opinion, though it has increased since 2007, when it was less than 20%, to the 34% of 2021 (see previous post).

These consultations from 2009-11 certainly showcase the process that has made the issue of independence part of mainstream political debate in Catalonia in the last 10 or so years, and which has turned Catalan nationalism into a secessionist movement, leaving behind the federalism that had been favoured since the early 19th century (and which remains the option most people in Catalonia support, mind you). The origins of this change in outlook may be found in a variety of recent political developments, some of which were more removed from the day-to-day of citizens than what may be appear to be the case at first. Read more »

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry.

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry. What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are. Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

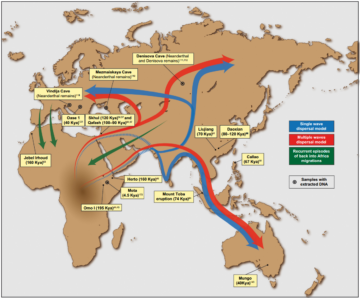

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors