by David J. Lobina

I naturally pose this question in the context of the series of posts on Language and Nationalism I have published here in the last few months. An example of a peripheral nationalist movement, the case of Catalonia will allow me to make my final message on these issues explicit enough, thus bringing the series to an end (this is the last entry; the previous 4 instalments are here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4).

Catalonia, a region in the north-east of Spain, is by any definition of nationalism one might have quite clearly a nation which is furthermore in charge of a significant number of state functions all of their own – namely, it has a devolved parliament, some control over fiscal policies, a local police force, and more. What Catalonia isn’t, of course, is an independent nation-state, though in the last decade or so political events in the region suggest that a sizeable portion of Catalans would be partial to changing that. So what do the people of Catalonia want? And who are the Catalans to begin with?

The answers to these questions are partly historical, but contrary to what is usually the case in discussions such as these, we don’t actually need to go too far back in history. This is of course in keeping with the point I have made in this series of posts that the concept of nationalism and the actual reality of nation-states are rather modern phenomena, no older than 200 years (and mostly European in origin). Curiously, however, it is often the case that many standard or official histories of a given country or nation start rather far back in time, and the case of Catalonia is no exception. The monumental Història de Catalunya [The History of Catalonia], for instance, first published in 1987-89 (in 8 volumes, expanded to 10 in 2003), starts in prehistorical times. There are no doubt many who will claim that in some cases the history of a nation does start much further back than 200 years ago; some nationalists from the Basque Country, for example, another region in the north of Spain, regard Basque culture as a 1000-year phenomenon, but this is an ideological viewpoint rather than a historical one and I shall not be concerned with this type of discourse here.[i]

As a matter of fact, Catalonia neatly exemplifies some of the (recent) historical processes underlying the nationalist phenomenon that I chronicled in Part 1, and this obviously suits my purposes well. This is despite the fact that Catalan nationalism, or Catalanism, is not a core nationalist movement but a peripheral one. As mentioned last month, Catalonia is not an independent nation but part of a greater polity, the nation-state of Spain, from whence it might want to secede. Whether the latter is the case or not in large part depends on what the fabric of Catalan society turns out to be.

The Catalans, as it happens, are not a homogeneous bunch, as numerous surveys from the Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió [The Centre for Public Opinion Research], a department of the devolved Catalan government, clearly show. In its latest study, dated May 2021, it is reported that 38% of those surveyed describe themselves as being as much Spanish as they are Catalan, 23% see themselves as being more Catalan than Spanish, almost 5% more Spanish than Catalan, 24% regard themselves as being only Catalan, and close to 4% as being only Spanish. Regarding their most dominant language (Catalans are as bilinguals as they come), a crucial aspect of one’s national identity, as we have seen in this series, 40% declare Catalan as their main language, for 39% for Spanish, with close to 19% stating that Catalan and Spanish are pretty much on the same level for them. As for the origins of those surveyed, close to 49% state that their father had been born outside of Catalonia, for 47% for their mothers (in either case, these parents were born predominantly in the South of Spain).

And what do the people who were surveyed in May 2021 think of the possibility of an independent Catalonia? 34% do indeed wish Catalonia to be an independent nation-state, for 25% who wish to see Catalonia as a state within a federal Spain, and 28% who seem happy with how things stand now – Catalonia as an autonomous community of Spain. A greater proportion of non-independentists than independentists, the cause for independence has historically been a rather minority option in Catalonia, its current high point something of a novelty (in 2007, the year I started my doctoral studies in Catalonia, and my first experience of the region, a mere 18.5% were in favour of independence). Indeed, Catalanism has of recent undertaken a great transformation, from being predominantly federalist in outlook to becoming a fully independentist movement, as discussed by the Catalan historian Enric Ucelay-Da Cal in a number of recent papers.[ii]

As a political phenomenon, Catalanism started in 1886, with the first Catalanist party, the Lliga de Catalunya [The Catalonia League], founded in 1887 as a Catholic and small-c conservative endeavour. During most of its history, in fact, Catalan nationalism has been in favour of either a federalist or confederacy state and during the early decades Catalanists were greatly influenced by the example of the State of South Carolina in pre-civil war US – South Carolina supposedly had a kind of “autonomy with a veto” status at the time, which appealed to Catalan nationalists as it seemed to provide a way to block policies from the central Spanish government that might not benefit Catalonia whilst remaining an important part of the overall state. Early Catalanists were also quite interested in the internal structure of the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires, a way of organising a state which they thought could function as a blueprint for Spain (this strand of Catalanism was of most interest to new political parties such as Unió Catalanista [The Catalanist Union], founded in 1891, and the Lliga Regionalista [The Regionalist League], founded in 1901). Fast forward past 40 years of repression during the Franco dictatorship, as well as 20 years of democracy with a Catalan conservative party in charge of a devolved parliament, and by 2003 the pursuit of greater sovereignty had become the main objective of Catalanism, to be replaced by an unambiguous independentist agenda in 2012. (I refer to the Ucelay-Da Cal’s articles I have linked to for details regarding this change of paradigm, which don’t interest me much here).[iii]

Before political nationalism, though, there was cultural nationalism in the form of the so-called Renaixença Catalana [Catalan Renaissance], a “revivalist” cultural movement the historian Pierre Vilar has it starting in 1787 but which was in full swing more properly in the 1850s, especially with a “re-edition” of the 14th century Jocs Florals [Floral Games], a poetry contest that in its 1859 version was meant to infuse the Catalan language (actually, the Catalan spoken in Barcelona) with proper institutional backing. Much as is the case with the Italian Risorgimento and similar cases elsewhere in Europe, these 19th century events were not really revivals; they instead created something entirely anew. There is certainly no continuity of any sort between the Floral Games of 1859 and those of 1323, the latter of which took place in a completely different language (namely, Occitan); nor is there a direct relationship between modern Catalan and older versions of the language, as I argued in Part 1 was also the case for Old English, Middle English, and modern English when these constructs are considered from the point of view of (generative) linguistics.

More to the point, and as the 19th century poet Carles Riba recognised (cited in Eric Hobsbawm’s important book on nationalism), in the modern world any given language requires extensive institutional support if it is to become a national language – in order, that is, to be standardised and moreover become the common language of a people – and this is of course one of the aims all nationalists in Europe were campaigning for at the time. That being said, institutional support is not always enough to guarantee the good health of a national language, as we shall see, and this is the predicament that the promoters of the Catalan language (or rather, of a specific variety spoken in Catalonia at the time) find themselves to this day.

So far, so congruent with the general account of nationalism I have outlined in this series (indeed, with the history of nationalism tout court). That is, Catalan nationalism started as the cultural concerns of some Catalan elites of the 18-19th centuries, with little direct connection to anything from the near past, let alone from medieval times, other than in the way the past was imagined to inform contemporary conditions by these very elites. At the time, there would have been myriad linguistic variants in the overall population, even within the elites themselves, and many of these languages would not have been mutually comprehensible, as I explained in Part 1 of this series (the reason, of course, is exclusively linguistic in nature).

Cultural events such as the Floral Games helped establish the more prestigious linguistic variant (as mentioned, the language spoken by the elites in Barcelona) as the standard Catalan language, which with the advent of universal schooling in the 19th century and beyond would soon become the common language of the local population. In time cultural nationalism derived into political nationalism; or to put the matter in terms of the three stages peripheral nationalisms typically go through (see Part 4), there were, first of all, the small groups of elites who think up a national identity, then there were the slighter bigger groups of elites who standardise the national language and (re)organise the cultural practices of the nascent nation, and finally we would have had the dissemination of the nationalist sentiment across a population that by then had been homogenised to a significant extent (one language, one set of cultural customs, etc.).

The problem with applying Miroslav Hroch’s framework (for it was he) to the Catalan case is that the Catalans, as shown, do not form a very homogeneous group. Indeed, Catalans live in a world in which the Spanish language and culture are not foreign to them at all and are in fact an important part of their own mental baggage. What’s more, the Spanish language and culture are in some respects rather dominant in Catalonia (though not so in the administration or the local government, as I remark below), and this is not on account of any policy from the central Spanish government, current or from the past. As Hobsbawm discusses in his aforementioned book, the adverse conditions local languages often encounter are rarely to be explained in terms of actual oppression or persecution, but often simply as a consequence of the advantages a more widely-used language enjoys, including the prestige such languages typically have.

This general situation has been the case in Catalonia for a long time now, compounded in the last 80 or so years by the high levels of immigration from the rest of Spain, especially from the south. What has been a novelty in recent times is the process of “catalanisation” that was initiated in the 1980s to turn the Catalan Parliament, all public bodies and subsided media, as well as the majority of all schooling and higher education, into exclusively Catalan-speaking places. An astonishing development for a society that was already fairly bilingual at the time, this policy has been rather aggressively pursued and indeed enforced. A policy that is often defended on account that the Catalan language is not as widely spoken or used in Catalonia as Spanish is (the often unstated assumption here is that what we call the Catalan language is intrinsic to the Catalan nation, or at least to a Catalan national identity, in a way that Spanish can never be), it is telling that this remains true to this day despite 40 or so years of following the policy religiously. Indeed, by 2013 around 75% of the population in Catalonia was said to be able to speak Catalan, for close to 100% in the case of Spanish, and the imbalances are more pronounced when we consider things like the production of culture (the arts, literature, etc.) or even the availability of the media overall (putting the Catalan state media to one side, which doesn’t broadcast in Spanish as a matter of policy). If anything, this is a good example of the point that no amount of state action can compensate for the imbalances that two languages with very different number of speakers and cultural outputs will always demonstrate, let alone reverse these relationships. And yet for a great number of people in Catalonia the state actively seeks to not speak to them in their own language – nay, to not even revert to the language they both speak.

*****

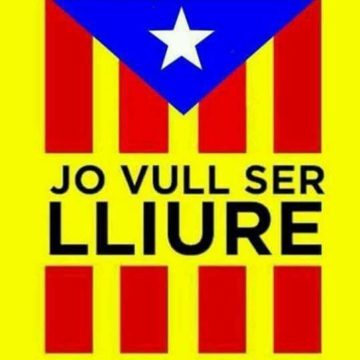

In the independentist flag that appears at the beginning of this post, a design based on the Senyera, a flag that can be traced back to medieval times as the coat of arms of the Crown of Aragon, the message in Catalan says ‘I want to be free’. Not a sentiment anyone would want to disagree with; unless, as I have been claiming in this series, such freedom is cashed out along nationalist lines. Or to quote myself:

Nationalism is often associated to such fundamental human rights as the self-determination of a people, and when the focus of attention falls upon small nationalist movements regarded as being oppressed in one way or another, usually by a greater nationalist movement, it is easy to sympathise with the objectives of such movements and forget all that is in fact reactionary to nationalism – the imposition of a language and a culture, the enforced contrast with other peoples, etc.

All nationalisms are exclusionary in one way or another, whether this is Spanish nationalism, Catalan nationalism, or any other instance anywhere in the world. The case of Catalonia is particularly illuminating because of the peculiarities of Catalan society. As mentioned, the population in Catalonia is as bilingual as it may be possible to be in a modern state, and the Catalan and Spanish identities co-exist with little friction, often within a single person. An outsider may perhaps be surprised by the fact that sectarian violence is non-existent in Catalonia, but this would be a case of viewing Catalan society through a rather skewed prism. The Catalan identity is a mongrel, incorporating as it does various aspects of what we might define, not with a little bit of artifice, prototypical or indeed stereotypical examples of Spanish and Catalan national identities (and I doubt the latter actually exist, or at least not any more; all national identities may be mongrels). But no-one ceases to be Catalan for writing the name of Catalonia in Spanish instead than in Catalan, to refer to a common (and recent) practice of some media in Spain, who write Catalunya instead of Cataluña even if the publication itself is in Spanish (an entirely performative gesture, in my opinion). And yet Catalonia is also a society in which a Catalan-speaking political class is almost entirely in control, and where the country is supposed to be first of all Catalan and then perhaps Spanish, if not in fact only Catalan. This is particularly unfortunate given that it doesn’t reflect the reality of Catalan society.

So what to make of recent events in Catalonia, especially the often-repeated claim that most of the population is in favour of holding a referendum to decide whether they want to be independent or not? I am certainly in favour of anyone’s right to decide their own affairs and indeed their future; the problem is not the principle, but the question that is asked in each case, and a yes-or-no referendum on independence is a far cry from people’s real concerns and their ability to have a meaningful say in their own affairs. Much more important are the multiple questions one can, and should ask and settle, regarding what type of society one wants, from the limits to the private ownership of the means of production to working out which sectors taxes should be allocated to, and many more. Indeed, I am of the opinion that talk of self-determination should not be couched in terms of abstract notions such as a people or a nation, but grounded in the affairs of the communities a person is actually in contact with. After all, everyone can relate to the desire to have a say in one’s own affairs, be this at school, at university, in the workplace, or in your own area of residence. But this simply reflects the universal human longing for autonomy of thought and action, in collaboration with others but with little to no top-down impositions, and this is a feeling that is present in Catalonia as much as it is in London, Santa Margherita Ligure, and Madrid. Or in fact anywhere.[iv]

[i] Or at least not in the main text; the endnotes are a different matter. I should add that most of the sources I will use here and in main text will be in Catalan or Spanish (and some in Italian), which I think may well provide a different perspective on the Catalan question to English-speaking readers. As for the deniers of my premise that we need not go back past the 200 years mark, to begin the endnotes on this issue, the noted Catalan historian Josep Fontana is a case in point. An esteem historian of 19th-century Spain and economic history in general, with an expansive knowledge of world history (his 2011 book, Por el bien del imperio [For the good of the Empire], a history of the world since 1945, is over 1200 pages long), his writings on the history of Catalonia, and on the character of Catalans, is a bit more interested, to put it that way. For a start, Fontana sees the period between 1283 (the year of the first constitution of the Corts [Courts] of Barcelona, local councils that were based on the so-called Usages of Barcelona, basically the customs of the city) and 1706 (the last year the Corts sat during the 1701-1714 War of the Spanish Succession) as demonstrative of a progressive process of democratisation in Catalonia (however geographically defined this is, an uncertain endeavour for the period; technically speaking, Catalonia was a principality within the Crown of Aragon for much of the middle ages). Moreover, according to Fontana, there was a clear Catalan identity in existence by the 18th century, in fact a sense of such an identity was already evident in the 14th century at a time when Catalonia can be described as a modern national state (regarding the last point, Fontana may have been influenced by the French historian Pierre Vilar, who claimed that Catalonia was the first nation-state in history, though his identity conditions for what constitutes a nation-state – basically, being a mercantile power with a capital city – are not a little suspect; a central figure in Catalan historiography, Vilar wrote introductions to each volume of the original publication of History of Catalonia, which were eventually collected and published as a book, where Vilar restates this point). Indeed, between 1469 (the year the Kingdom of Castile and the Crown of Aragon were united) and 1714 (the end of the War of the Spanish Succession), Fontana adds, Catalonia had its own laws, language, coinage, and political system. The set of features usually claimed to underlie a national identity and indeed a nation (the Basque nationalist Ramón Zallo calls these features a nation’s objective factors, part of a collective (!) project), the Catalan identity is not only based on sharing a language and a culture, Fontana tells us; it also includes sharing a social contract, making every Catalan the bearer of rights and freedoms. There is certainly a significant amount of historicism (and elitism) in these views, not to mention an unfortunate degree of Catalan exceptionalism (coincidentally Fontana’s national identity). But none of this withstands any sort of scrutiny, and for some of the reasons I went through in Parts 1 to 4 of this series on Language and Nationalism. To begin with, it is important to state that the Corts were not any different from other medieval bodies and charters, in the sense that these were instruments of the local aristocracy to protect their interests against the ruling Crown, in this case the Crown of Aragon, much as was the case with the Magna Carta in 13th century England and elsewhere in Europe (for instance, the Fueros in the Basque regions). As I have stressed in this series, sovereignty in the middle ages was a very fragmented affair everywhere in Europe, and the relative autonomy of a given region is neither here nor there when it comes to the history of nationalism; the majority of the people didn’t have a say in any of these charters, given that these documents were not popular enterprises in any sense. As a matter of fact, the Corts were overseen by the Crown and controlled by the aristocracy, the clergy, and from early modern history, the nascent bourgeoisie, leaving most people out of any democratising process, the vast majority of the population nothing at all like Fontana’s Catalan men and women of rights and freedoms. A world quite unlike our own and utterly dominated by the elites, the “language and culture” of Catalonia were in fact the languages and cultural customs of the elites, of which there were many varieties until standardisation properly started in the 18-19th centuries. The year 1714, when the War of the Spanish Succession ended, is an important date in the Catalan nationalist imaginarium, as it is taken to also mark the end of Catalan independence – a sign of Catalans rejecting Spain, as Vilar put it (Breve Historia de Cataluña [Brief History of Catalonia], see link above, p. 21). Notwithstanding the fact that the War of Succession was between two (foreign) royal houses (the Austrian Hapsburgs and the French Bourbons) over the vacant Spanish crown (and the dominions of the Spanish Empire) and not at all a case of a war between Spain and Catalonia, or indeed a case of Spain attacking or invading Catalonia, as usually depicted (as abstract an idea both Spain and Catalonia would have been at the time), the consequences of the decision of the Corts to back what turned out to be the losing belligerent affected for the most part the elites only (from 1716 the Corts and other local customs were officially abolished, though it is worth pointing out that enforcement at the time would have been rather limited). Like elsewhere in Europe, Catalan nationalism and the Catalan identity are phenomena that began in the late 18th century and properly belong to the 19th century, first originating within the elites, and then expanding to the rest of the population.

[ii] Catalan nationalists often talk of their inalienable right to self-determination, which they believe to be based on international law. As the (independentist) Catalan jurist Alfons López Tena has pointed out, however, a people’s right to self-determination, mentioned in the UN Charter but more properly a central article of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (indeed, it is Article 1), was formulated with colonised countries in mind, whereas the independence of Catalonia (or Scotland, for that matter) should be described as a case of secessionism instead – not at all the same concept.

[iii] At least not in the main text. I would like to add that this change in perspective wasn’t the result of a bottom-up development, but the very opposite, as is the case in the history of any nationalism. It may well have been one of the consequences of the long process of “catalanisation” that the conservative party of Jordi Pujol, the President of the Generalitat de Catalunya [roughly, a devolved Government of Catalonia] from 1980 to 2003, unambiguously undertook, even though this party, Convèrgencia i Unió [Convergence and Union, an alliance of two parties, in fact], never campaigned for independence during this time. I will eventually come to the issue of catalanisation in the main text, emphasising its limits, which result in a paradoxical situation for Catalan nationalists.

[iv] But what about the so-called ‘procés’ [the process], according to which Catalans were going to ‘disconnect’ from Spain, have an independence referendum all by themselves, and become an independent state unilaterally? That was certainly the rhetoric, but it was all for show, for internal propaganda, as the journalist Guillem Martínez has plausibly argued (for instance here, in Spanish). I intended to provide a whirlwind summary of events from 2003 to the present day in my last endnote, but I am very late this month and this piece needs to be submitted now (a shame, though, as I really wanted to diss Colm Tóibín in this note). I would be happy to expand this note, and summarise Martínez’s account by doing so, if anyone asks, though.