by Rafaël Newman

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

In 1977: Eine kurze Geschichte der Gegenwart (Suhrkamp, 2021), Philipp Sarasin deploys a novel methodology to determine the outlines of the present. His is a retrospective, thematic approach: one figured, like the Judeo-Christian narrative, by death and rebirth, but with an ambiguous and polymorphous turn. Sarasin, an intellectual historian who teaches at the University of Zurich, chooses as his foundational moment, and the stark title of his study, a year notorious among connoisseurs of Anglo-American pop culture for its symbolic passing of the baton between generations: the year in which Rock ‘n Roll was declared dead, only to be immediately resuscitated in the form of Punk; when Queen Elizabeth II was fêted throughout the Commonwealth during her Silver Jubilee while the UK languished in economic malaise and the Sex Pistols mocked the monarch from a boat on the Thames. 1977 is thus, viewed from a certain angle, an obvious facile hinge between sociological epochs. The key to Sarasin’s more complex method, however, is in his subtitle: “A Brief History of the Present,” with its echoes of popularizers like Stephen Hawking and Bill Bryson (the latter himself the author of a study devoted to one particular year), is also an insider’s reference to the journal Sarasin publishes with a collective of other historians in Switzerland and Germany. Read more »

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus.

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus.  Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

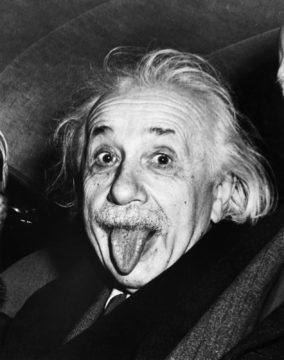

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant. Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021. If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.