by Jonathan Kujawa

Bob Moses was a moral giant who worked tirelessly to fundamentally improve the world for others. He came from a low-income family but, through talent and hard work, earned a degree from Hamilton College and a master’s degree from Harvard in the philosophy of mathematics. He left graduate school for family reasons. To earn a living he began to teach mathematics at a private school in New York City. After a few years, Moses read of the people his age who were conducting sit-in protests against segregation in the South and knew he had to join the struggle.

Moses was viewed with some suspicion when he first arrived. He was an academically inclined, Harvard-educated philosopher who seemed out of place in the hot, dangerous climate of the civil rights South. Suspicions were only heightened when they heard he spent free time attending a mathematics lecture at Atlantic University on the “Ramifications of Gödel’s Theorem” [2]. Soon enough they discovered he was the real deal.

But Moses was drawn not to the newsworthy sit-ins and protest marches, but to voter registration. And to voter registration in the most bitterly white supremacist corners of Mississippi, no less. It wasn’t just that there was segregation, or that the KKK terrorized, or even that lynchings were a frequent event. White supremacy was absolutely baked into the very structure of everyday life. The local and state police were enforcers. To register to vote required passing literacy and citizenship tests which were virtually unpassable for African-Americans. Even counties with an overwhelmingly black population had nearly no registered black voters. And many of the people in these counties lived in grinding poverty, earning only a few dollars a day farming or doing manual labor.

Moses saw that even if the sit-ins were successful, the result would only be the desegregation of public spaces. That’s not nothing, but it is far short of true equality. That’s as clear today as it has ever been. In the US segregation is a fading memory, but it is obvious that when it comes to some of the most important things — health, the justice system, the educational system, economic opportunity, etc. — we are a long way from equal.

Bob Moses recognized that voting and voter registration were necessary steps towards political power and real change. Of course, one goal is to elect politicians who can get the government to work on behalf of all its citizens. But more fundamentally, by standing up to be counted black voters forced others to see them as citizens and as human beings. And they would see themselves in the same light, maybe for the first time in a long time.

As Bob Moses described it, even before he could get the courthouse registrar to approve a voter registration, even before he could get someone to attend evening classes to learn the answers to the many questions about the state constitution they’d be asked, he had to convince a person who had spent their entire lives being ground down that registering to vote was a thing they could do, a thing they must do.

The very act of looking the courthouse registrar directly in the eye and insisting that they be given their constitutional right to vote was a revolutionary act. When you, maybe for the first time in your life, stand up and insist you be allowed to wield power must be a profound feeling.

As Moses wrote in Radical Equations:

…I liked to think I got anyone I spoke with imagining himself or herself at the registrar’s office. Getting someone to make this kind of mental leap, even for a moment, had to be considered an achievement in the Black Mississippi of those days where even the idea of citizenship barely existed.

It is little surprise that this terrified the powerful people in 1960s Mississippi. They threatened, arrested, bombed, burned, and murdered. County officials even decided to stop accepting federal food aid so as to punish the black community for their activities.

Moses also saw that the supposed allies of the civil rights movement were willing to trade away what was right when it served their purpose. As Bob Moses wrote when describing the events of the 1964 Democratic party convention:

…to this day I don’t think the Democratic Party, which has primarily organized around the middle class, has confronted the issue of bringing poor people into its ranks. We were challenging them on racial grounds, obvious racial grounds. We were challenging them to recognize the existence of a whole group of people — white and Black and disenfranchised — who form the underclass of this country.

Again Moses saw the deep structural sources of the problem. It wasn’t enough for black people to vote and be heard. That alone wouldn’t balance the scales of power.

In the late 1970s Moses returned to Boston. For a time he returned to Harvard to work on his Ph.D. thesis, but left once again when he saw a fundamental problem which he couldn’t ignore.

Through his children, Moses discovered the sad state of math education in the US. This was in the early 1980s, but he could see that math literacy would be as important as reading literacy in the computer age. When Moses was in Mississippi in the 1960s he saw the devastating effect on people when they weren’t able to keep up with technological change. As modern farming techniques spread, decent wages and job opportunities became ever more scarce. Without education and technical skills, people were inevitably left behind as capitalism churned forward.

Bob Moses saw high school algebra as the gateway to college readiness. Students who had a firm grasp of algebra when they left 8th grade could take advanced math and science classes in high school. Those who didn’t, couldn’t.

Bob Moses saw high school algebra as the gateway to college readiness. Students who had a firm grasp of algebra when they left 8th grade could take advanced math and science classes in high school. Those who didn’t, couldn’t.

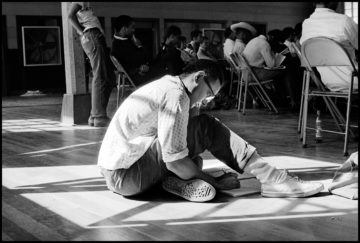

What started as tutoring three students in the corner of a classroom grew to thousands of students across the country (including rural Mississippi!). The Algebra Project developed a number of innovative instructional methods designed to make algebra accessible to students who might otherwise have been tracked into remedial classes. Lots of hands-on learning, math games, group work, putting the math into familiar contexts, etc.

These innovations organically grew out of working with the students. His experience as an organizer taught Moses the importance of listening to the needs, goals, fears, and dreams of those you are working with. By finding out what resonated with the students, the teachers in the Algebra Project were able to find ways to bring the math to the students.

Drawing on his experience with voter registration, Moses also knew the importance of internal motivation and peer support. When the going would inevitably get tough, just like the people going to the courthouse, the students needed to have internal strength and a community to carry them through. Even more, like the people registering to vote, the students themselves must believe it is their fundamental right to learn mathematics.

As Moses wrote in Radical Equations:

Like sharecroppers demanding the right to vote forty years ago when those in power said they did not vote because they were apathetic, our students will have to demand the education from those in power who say they do not get educated because they are dysfunctional.

In reading about his life, again and again I was struck by how Bob Moses approached every problem as a philosopher and a mathematician [4]. Moses thought deeply and carefully to identify the true problem and focused his attention there. He liked to identify the key axiom from which the rest should follow. For voting, it was “one person, one vote”. For teaching math, it was “If we can do it, we should do it”.

Bob Moses taught us that once you accept the first principle, the inevitable conclusion becomes a moral imperative.

[0] Image borrowed from the Algebra Project website.

[2] Indeed, Martin Luther King, Jr. himself had a chat with Bob Moses shortly after he arrived in Atlanta as there was some concern that he might be a Communist. Even rumors of a Communist connection in the 1960s would have been quite damaging to public support for civil rights.

[3] Image borrowed from the SNCC website.

[4] At least the Platonic ideal of a philosopher and mathematician. In practice, most are as shortsighted and quarrelsome as anyone.