by Bill Benzon

We all know that the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world. We also know that’s nonsense, pious and sentimental nonsense. Which is why it has been said so often.

The subtext, of course, is that the cradle-rocking hand is connected, through appropriate anatomical intermediaries, to a foot that’s chained to the dishwasher, the oven, the vacuum cleaner, and the sewing machine.

I would like to praise that cradle-rocking hand, even, in a sense, in its cradle-rocking mode. This cradle-rocking hand, we have been led to believe, is better at delicate manual tasks – I learned that as a child – than are men’s hands, the hands that shoot the guns, pilot the ship of state, and keep charge of the shackles connecting that associated foot to those many domestic appliances. That’s what I’m interested in, this hand with its delicate and versatile ability to make things, to make a world.

A Sampler

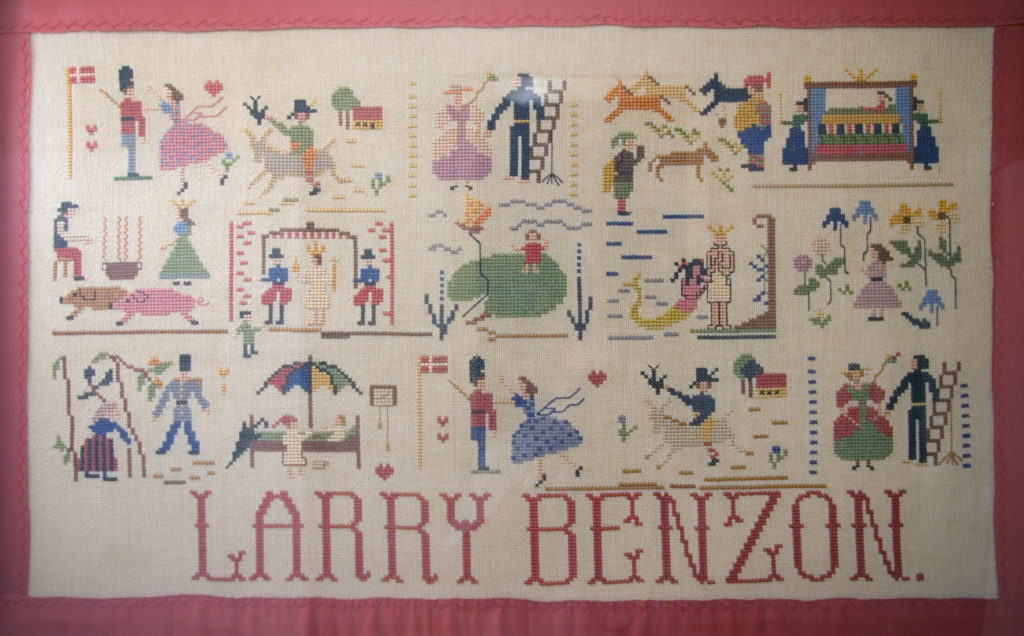

Here’s an example of women’s handiwork that I grew up with:

It is a sampler – that’s what it’s called – illustrating scenes from fairy tales by Hans Christian Anderson. It was done by a woman I never met, a great aunt who, I believe, was named Agnete. She was Danish, as were my paternal grandparents.

Such sewing skills were routine for women of her generation, born in the 19th Century. The making of a sampler was often a rite of passage for a  young girl. My mother was born in the early 20th Century, when women were also expected to be able to sew well. I can still hear the sound of her sewing machine and remember how I marveled at her skilled hands moving cloth beneath the needle. She also embroidered in both needlepoint and crewel styles.

young girl. My mother was born in the early 20th Century, when women were also expected to be able to sew well. I can still hear the sound of her sewing machine and remember how I marveled at her skilled hands moving cloth beneath the needle. She also embroidered in both needlepoint and crewel styles.

Such needlework was done in the home for family, though some women also did piecework for money.

My sister, Sally, suggested a poem by Stanley Kunitz written on the occasion of a 1974 exhibition of American folk art at the Whitney Museum. The poem is called “A Blessing of Women” and mentions specifically:

Bless Zeruah Higley Guernsey of Castleton, Vermont, who sheared the wool from her father’s sheep…Deborah Goldsmith, genteel itinerant…Mrs. Austin Ernest of Paris, Illinois… Bless Mary Ann Willson, who in 1810 appeared in the frontier town of Greenville, New York, with her “romantic attachment”, a Miss Brundage…Hannah Cohoon, who dwelt in the Shaker “City of Peace,” Hancock, Massachusetts, where a spirit visited her.

He concludes by blessing them in procession:

Bless in a congregation, because they are so numerous, those industrious schoolgirls, stitching their alphabets; and the deft ones, with needles at lacework, crewel, knitting; and mistresses of spinning, weaving, dyeing; and daughters of tinsmiths painting their ornamental mottoes; and hoarders of rags hooking and braiding their rugs; and adepts in cutouts, valentines, stencils, still lifes, and “fancy pieces”; and middle-aged housewives painting, for the joy of it, landscapes and portraits; and makers of bedcovers with names that sing in the night – Rose of Sharon, Princess Feather, Delectable Mountains, Turkey Tracks, Drunkard’s Path, Indiana Puzzle, Broken Dishes, Star of Lemoyne, Currants and Coxcomb, Rocky-Road-to Kansas.

Bless them and greet them as they pass from their long obscurity, through the gate that separates us from our history, a moving rainbow-cloud of witnesses in a rising hubbub, jubilantly turning to greet one another, this tumult of sisters.

Women’s hands were critical to Walt Disney and to other heads of animation studios back in the day. Those were the hands that inked and painted the cels that carried the movement of characters and objects in cartoons. Men designed and drew the characters, and the backgrounds as well, and animated them by drawing a succession of images. The finished drawings were then handed to the girls, as they were called at Disney, for inking and painting.

Without their work, there would have been no cartoons. And it is only because they did their work well that those cartoons look so very good, even today. And, as some of you know by now, I regard one of those cartoons, Fantasia, as one of the great works of 20th Century art.

How difficult is the work of inking and painting cels? In particular, is it as difficult as that which the men did, the designing, animating, and drawing?

The conventional answer, of course, is that it is not THAT difficult. For it is not creative, as designing and animating are.

I’m not so sure.

Let me suggest that, in making such judgments, we may not know what we’re talking about, that those judgments reflect ideology more than any deep knowledge of the requirements of the tasks in question.

Posh! You say. Paint by numbers, that’s all it is, paint by numbers.

Well, no, it’s not. First, the level of consistency and precision required is insanely demanding. The procession of religious in the “Ave Maria” episode in Fantasia was exacting because the figures were so very small in relation to the size of the cels, roughly the size of a sheet a typing paper. The problem was to produce a feeling of slow, but deliberate, forward motion as opposed to a nervous jitter. The inkers had to work quickly and with precision.

The problem is to get a smooth line that was accurately positioned to a small fraction of an inch. One way to do this is to use a guide, a straight edge for straight lines, a compass for circles and arcs, and a French curve or flexible curve for other curves. That’s how draftsmen did it in the old days of hand-drawn mechanical drawing; a craft I learned in high school during the early days of the Apollo Project. But animators don’t work like that nor do inkers.

They are working freehand. The only way to get a straight line in freehand drawing is to do it with a single stroke. The stroke has to be quick and smooth. The hand may be holding the pen, but the stroke must be made by the arm. And – this is the tricky part – it must trace the lines from the animators exactly.

It’s one thing to do a smooth single stroke line when you have complete control over the line. But the inkers don’t have any control over the line. They’re tracing a line that’s been given to them. They’ve got to eyeball the line, pick the beginning point and the end point, and then draw it. And remember they’re tracing a succession of images where the differences between one cel and the next may be small, so small that the width of the line itself mattered. If the inkers don’t position the line just so, the movement won’t flow on screen.

Just how good are they?

I put the question to the late Michael Sporn, an animator and director who has worked with the best in the business. Here’s what he told me:

The brilliant inkers Disney (and some of the other studios) had back in the grand days of animation, were able to get a good curve with a single stroke so that their nibs would give a beautiful thick/thin line. And this they inked with colored paints to match the colors of the characters.

The painting was a little easier in that it just required a consistent stroke, usually painted in little circles on the back of the cel. The hard part was keeping all the colors consistent. A Snow White dwarf, for example, might have 20-25 colors on it with all the shadowed lines added…

There aren’t too many today who can do this job.

It’s a constricting job which certainly would give one carpal syndrome. I once had it from my shoulder down to my elbow and could barely hold a pencil. A joint specialist gave me several shots of cortisone so that I could finish the film I was working on.

Still, it’s hard to think that inking and painting could be as challenging as animating. Animating is so free and requires such talent. While inking and painting are not free at all and require nothing but diligent application.

If that’s what you think — and believe me, I sympathize, because I find it very difficult NOT to think that way myself — let me offer a thought experiment of a kind suggested to me long ago by my mentor, the late David Hays. The idea is to gauge the difference between the best and the poorest performers in some domain by asking the performers to do it themselves.

In this case, we’re interested in inking and painting. The inkers and painters form something of a community. Those at one shop, such as Disney’s, will be fairly well acquainted with others at that shop, though not equally with all. And there will be some acquaintance among inkers and painters from different shops. In this thought experiment we’re going ask all of them each to name, say, the best five inkers or the best five painters they know. We’re going to tally up the votes and identify, say, the top 20%.

Now we have two skill levels. But there’s probably a range of abilities in that second, smaller group. So let’s repeat the procedure among them. Let each of them identify the best five among this smaller group. That will yield a third level of inkers with higher level of skill than the second level. We repeat this procedure until we’re left with no more than, say, five or so in the top group.

When we’re done, how many different skill-levels will have been sorted out? In the extreme we could imagine that none of them think anyone is any better than the rest. That gives us only one level. Or, maybe the whole group identifies a sub-group that’s better, but that sub-group is unable to identify any among them who’re better than the others. That gives us only two levels. But, what if this procedure identifies four or five levels of skill?

That’s pretty deep. If we did the same thing among animators, how many skill levels would be identified?

I don’t know.

Note, finally, that inking and painting is production line work. But then so is animation itself. That’s why the job was divided by senior animators, who drew the key frames, and in-betweeners, who interpolated between the keys. To be sure, making animated films isn’t doesn’t involve a production line like the assembly of cars and toasters, but it IS a production line. This is not home craft.

The musicians in the Nakagurose Elementary School band are mostly girls, though if you attend closely you’ll see a couple of boys.

When those girls get a bit older many of them will play in bands like this one, the Big Friendly Jazz Orchestra of Takasago High School. The drummer in this clip is fantastic (starting at roughly 1:30):

Bands such as this inspired Swing Girls, which won seven prizes at the 2005 Japanese Academy Awards.

And then we have professional musicians, such as Hiromi Uehara. She’s all over YouTube. You might want to start with this stunning performance of “I’ve Got Rhythm” from 2008:

Here she is in a 2004 interview with Marian McPartland, grande dame of jazz piano.

* * * * *

Who in their right mind wouldn’t aspire to women’s hands?