by Callum Watts

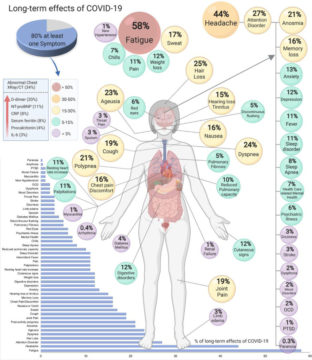

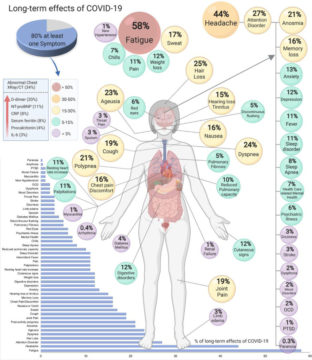

Almost two years ago I caught COVID-19, and became quite sick for a month. Luckily I did not require hospitalisation. I was then in various states of more or less debilitating ‘unwellness’ (I use this because the word sickness does not seem to quite capture it) for about 6-8 months. I don’t think I felt ‘normal again’ till probably a year later. I’m not convinced I’ve returned to my full previous health. But all in all, if I treat that then/now comparison as an unhelpful rumination (which it is), I’d say I’m now in good physical health. Having said that, I find the phenomena of long COVID interesting and I still read first hand accounts of people experiencing long COVID as well as research on the subject. Recently the WHO has given the condition an official definition. This has caused me to reflect back on my own experiences and try to understand what, if anything I’ve learnt from it.

If I try to remember the sleepless nights, nausea, intense fatigue, palpitations, hot and cold flushes, and brain fog, they all seem very distant now, like they happened to someone else. I find it difficult to even imagine how low I felt. Similarly, when I try to pinpoint the moment at which I felt better, I find it extremely hard to pick it out. It’s almost like trying to remember when I went from being a child to an adult – I know it happened to me, I know that it involved really deep changes in myself, but trying to think back to the before and after feels impossible. I do know that at some point the amount of time I spent thinking about long COVID diminished and the amount of time I spent thinking about “everything else in life” increased. When I think about that recovery, that psychological shift seems at least as important as the physical improvements. Not only did the psychological shift support my physical recovery, but my physical recovery also allowed me to focus on the rest of my life again. If I were to experience a post viral condition again, I would focus predominantly on my psychological well-being rather than changes to my physical symptoms. In the grip of a mild chronic ailment, your mental response to it will have an enormous impact on your ability to feel like you are actually living your life again.

Yet at my worst I was utterly obsessed with how my body felt, like a berzerk cartographer trying to map every mi llimeter of an alien landscape. Oddly enough this acute awareness of my physical condition completely alienated me from my own body. The same paradox was present in my relation to my recovery. Constantly focussing on the measurable signals that might suggest I was getting better, I was almost completely unable to connect with a subjective experience of recovery. These psychological effects of COVID were in many ways harder to shake off than its physical impact.

llimeter of an alien landscape. Oddly enough this acute awareness of my physical condition completely alienated me from my own body. The same paradox was present in my relation to my recovery. Constantly focussing on the measurable signals that might suggest I was getting better, I was almost completely unable to connect with a subjective experience of recovery. These psychological effects of COVID were in many ways harder to shake off than its physical impact.

When I was unwell, I spent a great deal of time reading and speaking to people who either had long COVID or had recovered from it. I was frequently communicating with other ‘long-haulers’ online and reading scientific and popular articles about the disease. I was completely focussed on trying to understand what was happening to me. And even though I’m still deeply intrigued by the topic of the long covid and the relationship between mental and physical health, I’m wary of diving too deep into the topic again. However, I’m also curious as to whether other people could avoid having experiences as prolonged or as unpleasant as mine, and whether anything in my own experience is relevant to what other people are experiencing.

But here I experience a sort of paradox. The insight I have about the importance of psychological improvement for physical improvement could be summarised into the thought that if you are suffering from long COVID, try and avoid focussing on it at the expense of everything else in your life, but this isn’t quite right. When I felt like I was losing my grip on reality and long COVID wasn’t really ‘a thing’ yet, I found it validating and helpful to hear about other people having similar experiences to mine. It meant I wasn’t alone, and there was a name for the thing I was experiencing. There was a community I could talk with who could help me manage the uncertainty and demystify the condition. In turn I could help and support and reassure others. On the other hand, the more I spent time on blogs, or online groups focussing on long covid, discussing the minutiae of the symptoms, the mechanisms by which they might work, the more isolated I felt from the very life I wanted to get back to. At some point it was necessary to extract myself from these habits because they were preventing me from productively using the little energy I had on anything other than long covid talk. But how could I tell when this point had arrived? How did I know that validation was becoming fixation? How far was it even a conscious decision at all? What was cause and what was correlation? I genuinely cannot answer those questions with much confidence. And even if I could, experiences of long covid vary enormously in presentation and severity, what worked for one person may not work for another.

But one thing I am reasonably confident on is the difficulty of the digitification of recovery. Online reading and networks can only take you so far. During lockdown it was especially hard to access real world interactions, to some extent looking for digital resources and networks was inevitable. But these things are only a poor simulacra for real validation, information and support. Like other digital phenomena, they tend to suck in time, energy and send you tumbling down certain sorts of internet rabbit holes. They can distract you from the real things happening around you, from friends and family, from experiencing your own body. They encourage applying a label to oneself which can turn into an identity, and ultimately a prediction. If I had to experience the whole thing again, I would spend as little time thinking about long COVID as I could, and focus all my energy on pretty much anything else. This may not have accelerated physical recovery, which was slow, halting and required constant rests and little setbacks, but it would have sped up the psychological escape no end.