by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Akim Reinhardt

I was about 10 miles up the road in Long Beach visiting my sister’s family when word came of last week’s massive oil spill in Huntington Beach, Orange Co., California. We were actually headed over to that very beach when my brother in law checked the conditions.

Uh oh.

Ten or twenty years ago I might’ve made some tired, easy joke about how this state is a tragicomic carousel of disasters. Earthquakes, mudslides, droughts, riots, etc. Just add this oil spill to the list. But now it’s the entire nation that resembles a bad joke with punchlines you can smell long before they arrive.

And if this state is a microcosm of the larger nation, with about 12% of the U.S. population within California’s badly angled borders, then perhaps it has something to do with how money both creates and sorta solves problems, at least for some people. The wealthiest state in the world’s wealthiest nation, and neither can get out of their own way. They both stumble about, knocking everything over amid their ravenous search for profits, and then turn to the “regular people,” the actual workers with sigh-inducing lives and miserable commutes, and even the less fortunate, to foot the bill and clean it all up.

America, can’t abide by simple rules designed to keep a pandemic in check because you’re susceptible to the propaganda actively or passively spewed by profiteering TV networks and digital media? Then just spend lavishly to hog the world’s vaccine supply and ride out the worst of it while maintaining your freewheeling ways.

California, don’t have enough water to support both, 40 million people and an enormous, misguided agribusiness complex in a state that’s mostly desert or near-desert? Then spend decades building and maintaining massive hydro reallocation projects that wreak ecological devastation for hundreds of miles around. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

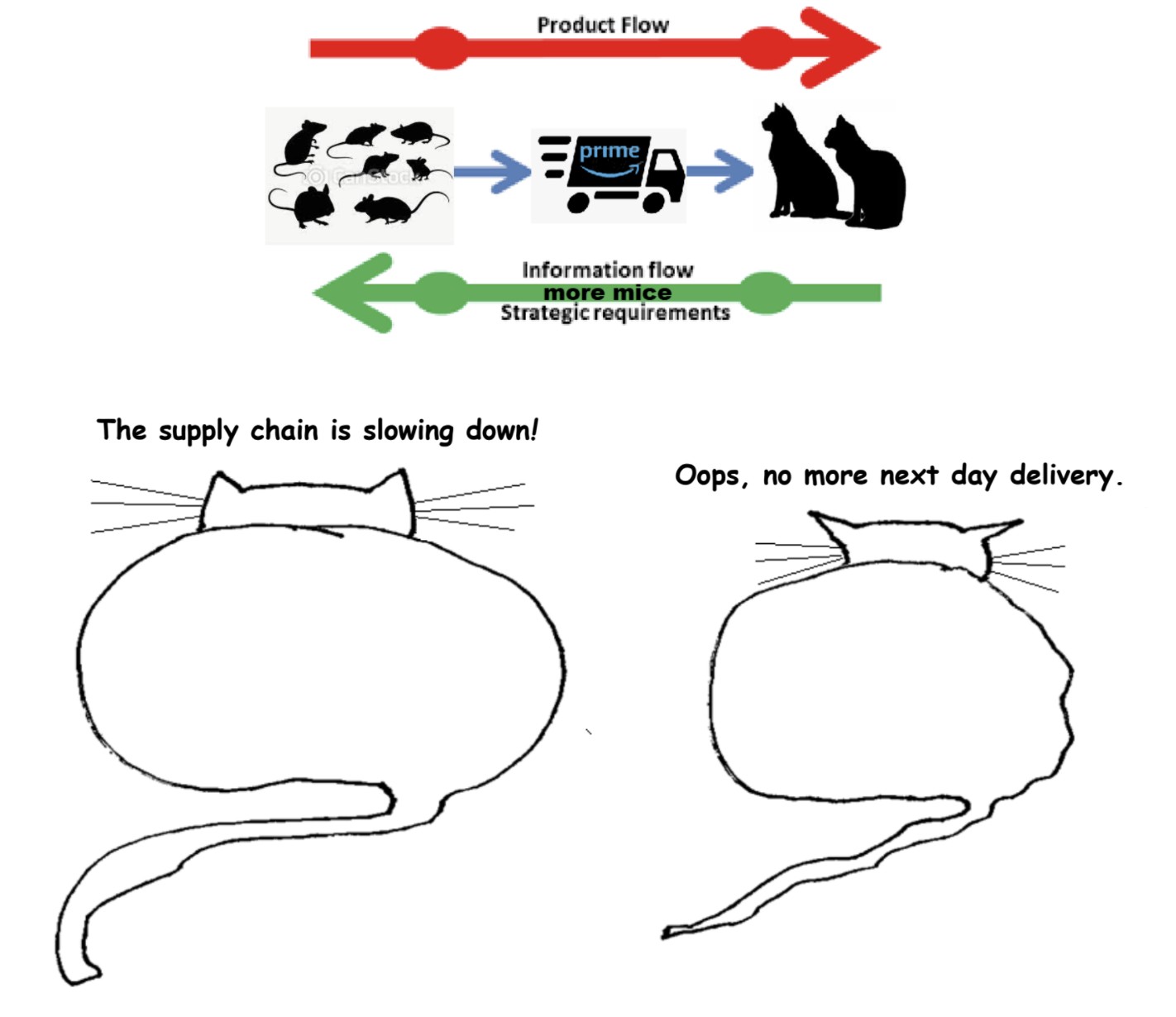

In 1977: Eine kurze Geschichte der Gegenwart (Suhrkamp, 2021), Philipp Sarasin deploys a novel methodology to determine the outlines of the present. His is a retrospective, thematic approach: one figured, like the Judeo-Christian narrative, by death and rebirth, but with an ambiguous and polymorphous turn. Sarasin, an intellectual historian who teaches at the University of Zurich, chooses as his foundational moment, and the stark title of his study, a year notorious among connoisseurs of Anglo-American pop culture for its symbolic passing of the baton between generations: the year in which Rock ‘n Roll was declared dead, only to be immediately resuscitated in the form of Punk; when Queen Elizabeth II was fêted throughout the Commonwealth during her Silver Jubilee while the UK languished in economic malaise and the Sex Pistols mocked the monarch from a boat on the Thames. 1977 is thus, viewed from a certain angle, an obvious facile hinge between sociological epochs. The key to Sarasin’s more complex method, however, is in his subtitle: “A Brief History of the Present,” with its echoes of popularizers like Stephen Hawking and Bill Bryson (the latter himself the author of a study devoted to one particular year), is also an insider’s reference to the journal Sarasin publishes with a collective of other historians in Switzerland and Germany. Read more »

by Callum Watts

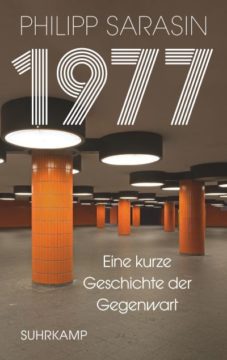

Almost two years ago I caught COVID-19, and became quite sick for a month. Luckily I did not require hospitalisation. I was then in various states of more or less debilitating ‘unwellness’ (I use this because the word sickness does not seem to quite capture it) for about 6-8 months. I don’t think I felt ‘normal again’ till probably a year later. I’m not convinced I’ve returned to my full previous health. But all in all, if I treat that then/now comparison as an unhelpful rumination (which it is), I’d say I’m now in good physical health. Having said that, I find the phenomena of long COVID interesting and I still read first hand accounts of people experiencing long COVID as well as research on the subject. Recently the WHO has given the condition an official definition. This has caused me to reflect back on my own experiences and try to understand what, if anything I’ve learnt from it.

If I try to remember the sleepless nights, nausea, intense fatigue, palpitations, hot and cold flushes, and brain fog, they all seem very distant now, like they happened to someone else. I find it difficult to even imagine how low I felt. Similarly, when I try to pinpoint the moment at which I felt better, I find it extremely hard to pick it out. It’s almost like trying to remember when I went from being a child to an adult – I know it happened to me, I know that it involved really deep changes in myself, but trying to think back to the before and after feels impossible. I do know that at some point the amount of time I spent thinking about long COVID diminished and the amount of time I spent thinking about “everything else in life” increased. When I think about that recovery, that psychological shift seems at least as important as the physical improvements. Not only did the psychological shift support my physical recovery, but my physical recovery also allowed me to focus on the rest of my life again. If I were to experience a post viral condition again, I would focus predominantly on my psychological well-being rather than changes to my physical symptoms. In the grip of a mild chronic ailment, your mental response to it will have an enormous impact on your ability to feel like you are actually living your life again. Read more »

by Bill Benzon

We all know that the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world. We also know that’s nonsense, pious and sentimental nonsense. Which is why it has been said so often.

The subtext, of course, is that the cradle-rocking hand is connected, through appropriate anatomical intermediaries, to a foot that’s chained to the dishwasher, the oven, the vacuum cleaner, and the sewing machine.

I would like to praise that cradle-rocking hand, even, in a sense, in its cradle-rocking mode. This cradle-rocking hand, we have been led to believe, is better at delicate manual tasks – I learned that as a child – than are men’s hands, the hands that shoot the guns, pilot the ship of state, and keep charge of the shackles connecting that associated foot to those many domestic appliances. That’s what I’m interested in, this hand with its delicate and versatile ability to make things, to make a world.

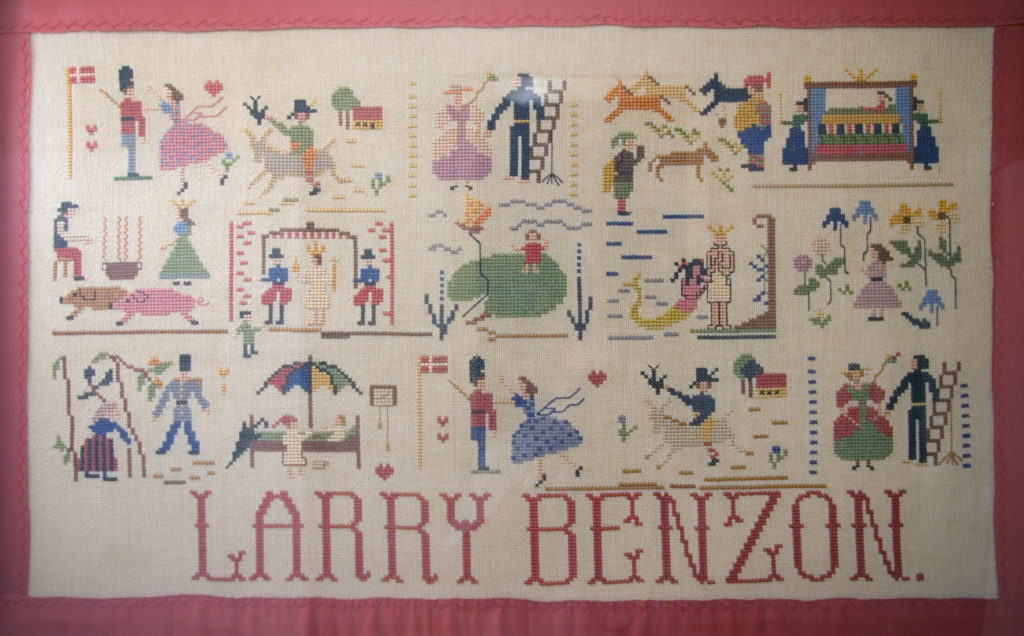

A Sampler

Here’s an example of women’s handiwork that I grew up with:

It is a sampler – that’s what it’s called – illustrating scenes from fairy tales by Hans Christian Anderson. It was done by a woman I never met, a great aunt who, I believe, was named Agnete. She was Danish, as were my paternal grandparents. Read more »

by Bill Murray

Last month, local people drove fourteen hundred dolphins to the end of Skálafjordur Bay near the capital of the Faroe Islands and killed them. It is a tradition called the grindadráp. In Icelandic, one of the neighboring languages, “Good luck” is hvelreki, with an idea something like “may a whole whale wash up on your beach.” The Faroese don’t wait for luck to produce whales. They sail out and find them.

When a fishing boat or a ferry spies a pod of whales (dolphins in this case but usually whales), a call goes out and word races through the village. Even in the middle of a work day people drop what they are doing and muster. Fishing boats form up in a half circle behind the whales and, banging on the sides of the boats and trailing lines weighted with stones, press the whales into a shallow bay.

Townspeople wait on the beach with hooks and knives. Mandated under new regulations, two devices, a round-ended hook and a device called a spinal lance are designed to kill the whales more quickly and thus, grindadráp proponents say, more humanely.

The hunter plunges the hook attached to a rope into the whale’s blowhole. Men line up tug of war style to pull the whale onto the beach. It takes a line of men to haul them out, for pilot whales may weigh 2500 pounds. The grizzled fisherman, the mayor, the hardware clerk with a bad back, all the townspeople fuse in common cause, shoulder to shoulder on the shore, harvesting the meat, dividing the spoils. Read more »

by Sarah Firisen

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus. Combined with contactless ordering, this seemed to be even more prevalent in the UK. We found QR code menus and contactless ordering in many restaurants and almost every pub we ate in. I loved it. It was quick, efficient, and accurate. We were able to pay immediately and didn’t have to sit around waiting for a check. And of course, as well as the hygiene rewards of contactless ordering, it somewhat mitigates the staffing issues. Having gone down this path, it’s hard to see why restaurants would go back to using only wait staff.

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus. Combined with contactless ordering, this seemed to be even more prevalent in the UK. We found QR code menus and contactless ordering in many restaurants and almost every pub we ate in. I loved it. It was quick, efficient, and accurate. We were able to pay immediately and didn’t have to sit around waiting for a check. And of course, as well as the hygiene rewards of contactless ordering, it somewhat mitigates the staffing issues. Having gone down this path, it’s hard to see why restaurants would go back to using only wait staff.

I experienced the opposite of this innovation on a recent visit to Macy’s in Herald Square in New York. Visiting the largest department store in the world is never for the faint of heart, but during any kind of sale, it’s pretty hellish. And it seems they’ve managed to make this experience even worse post-COVID. It used to be the case in the shoe department that you’d find a style and then wave down a sales associate. They would then disappear into the back and find the right size. Now, I had to wait in the long line at the cash register to ask the harried sales assistant who was also trying to operate the cash register.

I’m assuming that this is also related to staff shortages. The sales assistant used a mobile app to scan the barcode on the shoe and lookup size availability. Here’s what I don’t understand; Macy’s has a pretty good customer mobile app. You can use it to scan the barcodes on items to do a price check. Why on earth wouldn’t they integrate the shoe stock lookup app that they already have into the customer app? Then customers could request shoe sizes, and an associate could pull them from stock and bring them out. This seems like a missed opportunity to innovate out of the disruption caused by COVID and its aftermath.

Some industries and businesses have figured this out better than others. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

One time I had found an error in the proof of a proposition in a widely-read article on Growth Theory recently published by Hahn (jointly with Robin Matthews). I was pretty sure that their proposition was correct, but not the way they proved it. The morning I showed this to Hahn in a Department common room, he and several others got busy on the blackboard with constructing an alternative proof, but all of them failed. At one point Mirrlees entered the room and asked what was going on. He looked from a distance for a few minutes at the futile attempts on the board, and then proceeded to another part of the board, and wrote down a neat proof. Everyone in the room clapped. His method of proof also gave me an idea in proving some propositions later in my dissertation.

In Cambridge your supervisor cannot be your examiner, the dissertation has to be approved by two examiners, one internal (to the university), the other external. Mirrlees eventually was appointed my internal examiner. Incidentally, later Mirrlees also became the internal examiner on Kalpana’s dissertation, even though her work was not on theory, but on Indian agriculture. I used to tell Jim that while other people had a family doctor, we had in him a family examiner. Whenever he and his first wife Gill (who I think was a school teacher) went to a dinner party, and economists indulged in their bad habit even there of talking technical economics, I used to notice Jim’s sweet gesture in valiantly trying to whisper into Gill’s ears translations of those technical arguments in more comprehensible language. (He later lost Gill to cancer). Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

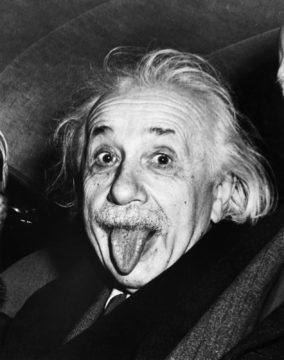

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

But in judging Einstein’s superlative achievements, both in terms of his birth and his evolution as a physicist, it is easy to think him of him as an entirely self-made genius. Nothing could be further from the truth. Einstein stood on the proverbial shoulders of giants – Newton, Mach, Faraday, Maxwell, Lorentz, among others – men who had laid the foundations of physics for two centuries before him and who he always had effusive praise for. But quite apart from learning from his intellectual ancestry, Einstein also honed useful habits and personal qualities that enabled him to triumph in his work. Too often when we read about brilliant men and women, there’s a tendency to enshrine and emphasize pure intellect and discard the personal qualities, as if the two were cleanly separable. But the fact of the matter is that raw brilliance and qualities are like genes and culture, each feeding off of each other and nurturing each other’s growth and success.

As psychologist Angela Duckworth described in her book “Grit”, genius without effort and determination can fail, or fail to live up to its great promise at the very least. And so it was for Einstein. Which makes it a matter of curiosity at the minimum ,and more promisingly a tool for measurably enhancing the efficiency of our own more modest work, to survey the personal qualities that Einstein embodied that made him successful. So what were these? Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

Bob Moses was a moral giant who worked tirelessly to fundamentally improve the world for others. He came from a low-income family but, through talent and hard work, earned a degree from Hamilton College and a master’s degree from Harvard in the philosophy of mathematics. He left graduate school for family reasons. To earn a living he began to teach mathematics at a private school in New York City. After a few years, Moses read of the people his age who were conducting sit-in protests against segregation in the South and knew he had to join the struggle.

Moses was viewed with some suspicion when he first arrived. He was an academically inclined, Harvard-educated philosopher who seemed out of place in the hot, dangerous climate of the civil rights South. Suspicions were only heightened when they heard he spent free time attending a mathematics lecture at Atlantic University on the “Ramifications of Gödel’s Theorem” [2]. Soon enough they discovered he was the real deal. Read more »

.I b well enough.

work’s fairly regular— ’bout 4-5 hours a day at regular pay,

plus a couple of side jobs drawing, lucky to have work

chug chug

keep my hand in the writing game: blogs, two local paper gigs

shooting my mouth off at greedy vampire windmills sucking global blood

working at finishing the room downstairs under the kitchen

have not been writing poems though, ‘cept this —it comes it goes

breath flows till it won’t:

interesting set of circumstances without comprehensible explanation

mysterious as sunlight flooding somewhere

lifting us on swells of gravity

it rose again today!

happy and light bouncing off glittering frost bright and beautifuller

than any precious metal a commodities speculator might hoard

grass beneath more verdant and moist than the greenest suck of banker’s air

crisper than a fresh thousand dollar bill, as breathable as necessary,

almost fine almost sweet

things change

..

’Bout you?

…

Jim Culleny

11/6/11

by David Oates

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

The “end times” got preached regularly from our Baptist pulpit, and during the summer a traveling evangelist would offer several days of extra-scary sermons, whoo boy, could that guy paint a picture! And we’d get scared all over again.

And yet, somehow, all of the various Beasts and Final Battles have failed to materialize. The Late Great Planet Earth spins forward in its usual way, bestselling doomsters notwithstanding, and lo, now I have arrived at my seventy-first year in this cavalcade of dread. Intact. Unscathed. Or anyway only mildly scathed. It’s been prediction, prediction, prediction. . . then nothing.

Funny how that happens. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

I sit in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in this the 19th and penultimate arrondissement. We are a pocket of American students lounging down by the perfectly circular pond. We rehash old jokes in unapologetic English which go unheard by the hundreds of Parisians sitting on the hill like Greek citizens watching lesser and stupider gods. It is the weekend so we cross the city on the Métro and by pure luck make it to our destination and once we’ve arrived we mispronounce the name of this handsome park.

Right at the edge of the water stands a man who rips off pieces of bread from the bakery and throws them to the mallards who flock before him. The duck man loves them and they return the feeling. But he so hates the pigeons which walk up to him on the grass and seek the crumbs he throws to the mallards. When they approach he kicks at them; and if they watch from nearby, he chases them with a fallen bough from a horse chestnut tree. He smokes something that is not tobacco and is not cannabis. It smells pleasant enough. It makes him more relaxed and still more vicious towards the approaching pigeons.

We sit by the water and some of us watch him. We are New Yorkers though most of us have only been in New York for a year or two because our time spent studying at Washington Square was cut short by the pandemic. And in New York at Washington Square there is no duck man and there is the pigeon man. We loved to see him enveloped by the purple green flashes of gray feathered flock. He let every oil-slicked feral disfigured city bird onto his lap and onto his shoulder and head. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

Since future people will have much worse lives, it seems that we owe it to future generations to do something now. But if we do things differently now, it will have the side-effect of bringing into existence different people than those that would have been brought into existence if we did nothing.

That might sound strange. But if you procreate in October instead of December, if you go build windmills and delay going to college and so meet someone else or the same person at a different time, if you do almost anything differently the children you have will not be the ones you would have had.

If we do nothing, do people in the future have a right to complain that we made their lives much worse? Here’s the odd bit. The future people who have better lives because we acted, and the ones who have worse lives because we didn’t, are not the same people. As long as your life is worth living, you can’t complain about things done before you existed that helped bring you into existence, because if any of them had been different, very likely you would not exist. Again, as long as your life is worth living the choice is not between you having a better or worse life, it’s a choice between existing and not existing.

That seems crazy, right? Philosophers call it the nonidentity problem. Read more »

by Peter Wells

Corporal punishment is a sickening and ugly procedure. Apart from the fact that one person is deliberately hurting another (usually smaller) at close quarters, it is often associated with anger, and even sadism. It is too often administered without reflection, too soon after a perceived offence has been committed. It is humiliating for the victim, especially if done in public, possibly causing lasting resentment and/or low self-esteem. It may encourage the development of violent attitudes among its recipients. The recent efforts to outlaw it are therefore humane and well-intentioned and, as far as they go, praiseworthy.

Unless, as in the case of Capital Punishment (q.v.), the alternatives turn out to be worse.

Let us look in turn at three loci in which corporal punishment has been used (and is now outlawed) in the UK: school, the home, and the criminal justice system.

As a teacher for half a century, I’ve given a lot of thought to how classes might be managed and children’s misdemeanours dealt with, and much has changed in that time. In the past, in addition to formal canings or beatings, administered by a headteacher or a responsible deputy, teachers in the classroom were given unofficial licence to strike children – which, as they were usually sitting in desks, meant hitting the part of the body most exposed: the head. Sometimes they threw things – chalk, if you were lucky. Aside from the obvious physical danger of this practice, it was inconsistent and suffered from flawed motivations. Teachers developed irrational hatreds for particular students, and therefore punished them with exceptional savagery. They were sometimes angry for some extraneous reason. The relationship between the crime and the punishment was ill-defined. I can remember dropping off to sleep in a warm classroom after lunch, and waking to find my head ringing from a blow, my spectacles broken on the floor beside me, and the red face of my French teacher a few inches from mine, roaring with rage. QED – it was a long time ago, and I still remember it vividly! And I particularly resented it because I was a keen student, who normally kept to the rules. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Varun Gauri

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

In his confirmation hearings, Justice Roberts, like a Clark Kent intent on hiding his true identity, possibly embarrassed by the size of his ambitions and self-conception, adopted a pose of humility: On the bench, Roberts said, he would just call balls and strikes. No one goes to a ball game to watch the umpire. He wouldn’t pitch or bat, just call ‘em like he saw ‘em.

The metaphor can’t work for an apex constitutional court. The whole point is that the court has final say over the interpretation of the constitution; in other words, the justices determine the rules of the game, not just the size of the strike zone, at the margins. Nor does the metaphor work for lower level courts, which do not merely apply statutory law and judicial precedent, but strategically push the boundaries of laws, rules, and extant court opinions, which themselves are often purposefully vague or discretionary. As if umpires were saying, “Strike three! In my opinion. For now. If so and so is true.”

The metaphor also fails because umpires are participants in the game of baseball. They enforce the rules. If a batter says, “I know that’s three strikes, but I’m staying up here and taking another swing, anyway,” an umpire righteously tosses the batter from the game.

In contrast, in the United States (and most other countries) judges typically don’t enforce, or even monitor the effects of, their rulings. Read more »

by Chris Horner

The political world is changing again. In place of the neoliberal politics of the last decades, capitalism and the nation state is undergoing one of its periodic metamorphoses. The period of what Nancy Fraser has called ‘neoliberal progressivism’ – broadly progressive stances by many governments on issues of sexual choice, reproductive rights and so on, coupled with an economic agenda committed to ‘balancing the books,’ actually cutting public expenditure, austerity in other words, is slowly giving way to a new dispensation. This new approach is unsurprisingly favoured mainly by parties of the right, and it threatens to leave centre left parties with a problem. This hasn’t happened in every developed country in the same way, and like any political phenomenon, it is subject to the ebb and flow of electoral fortune. But whether the right is formally in power or not, the we can see a family resemblance in the different forms that the right has recently taken. Read more »