by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

One of his many stories involved his trip to rural Egypt. He was traveling in the countryside in a car in the early evening. He saw a big field in one village where people were gathering for a cinema show; he stopped there, and as he walked closer to the place he saw that the large screen was made of rather thin paper. So he asked his Egyptian companion why it was paper, not the usual cloth screen; the latter asked him to wait, he’d soon know why. Then the film started, and sure enough it was a Bombay film, where at the beginning the villain was winning both in the fight scenes with the hero and also in the love scenes with the heroine. As this went on for some time the viewers were getting angrier and angrier, at one point they couldn’t take it anymore, they all stood up and with great fury started throwing their little knives at the screen, which soon got badly perforated. The projector was then stopped, and another paper screen was installed before the film could continue to its ultimate crowd-satisfying end. Read more »

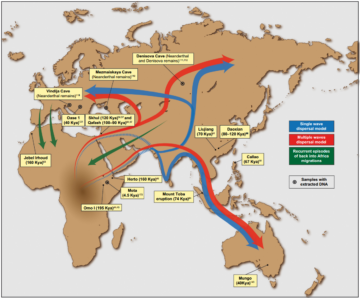

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom. My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

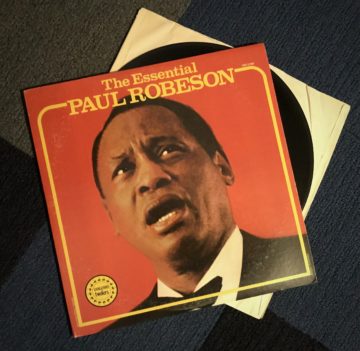

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.