by Usha Alexander

[This is the fifteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

At the same time, a few conclusions have begun to coalesce in my mind. Some of these may seem controversial, largely because they run contrary to the common narratives that anchor our dominant understanding of how the world works—our stories of human exceptionalism, technological magic, and the tenets of capitalist faith. Indeed, many of my own assumptions and worldviews have been challenged, altered, or broken. In their stead, new ways of thinking have taken root, as I began seeing through at least some of our most cherished cultural fabrications to understand our quandary with a different perspective.

Learning these things has been emotionally taxing, but I don’t believe there’s any way forward without a clear-eyed, big-picture view of our planetary and civilizational plight. And so, for better or worse, I wish to sum up my thoughts here, before ending my explorations through this series, which I next expect to turn toward thoughts on how one might respond to it all: hope, despair, expectation, fear, carrying on, looking ahead, finding new stories. I trust there are others out there, who would also rather reckon with what’s happening than go on pretending we needn’t adjust our expectations for the future… although, I confess, there are certainly days when I envy those who are able to go on pretending. What follows isn’t for the faint of heart: Read more »

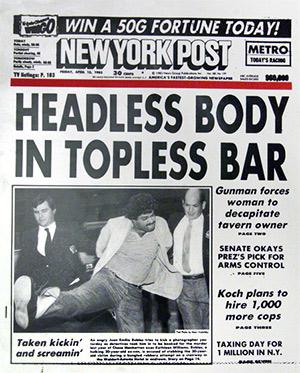

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology.

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology. Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods

At MIT outside the Economics Department there was one scholar, whose several lectures I have attended was Noam Chomsky. I knew of him as a pioneer in modern linguistic theory, but his fame in the outside world is as America’s topmost dissenter (his position is somewhat like what used to be that of Bertrand Russell in Britain, a towering figure in his own subject philosophy, but his fame outside was that of Britain’s leading dissenter).

At MIT outside the Economics Department there was one scholar, whose several lectures I have attended was Noam Chomsky. I knew of him as a pioneer in modern linguistic theory, but his fame in the outside world is as America’s topmost dissenter (his position is somewhat like what used to be that of Bertrand Russell in Britain, a towering figure in his own subject philosophy, but his fame outside was that of Britain’s leading dissenter).

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural.

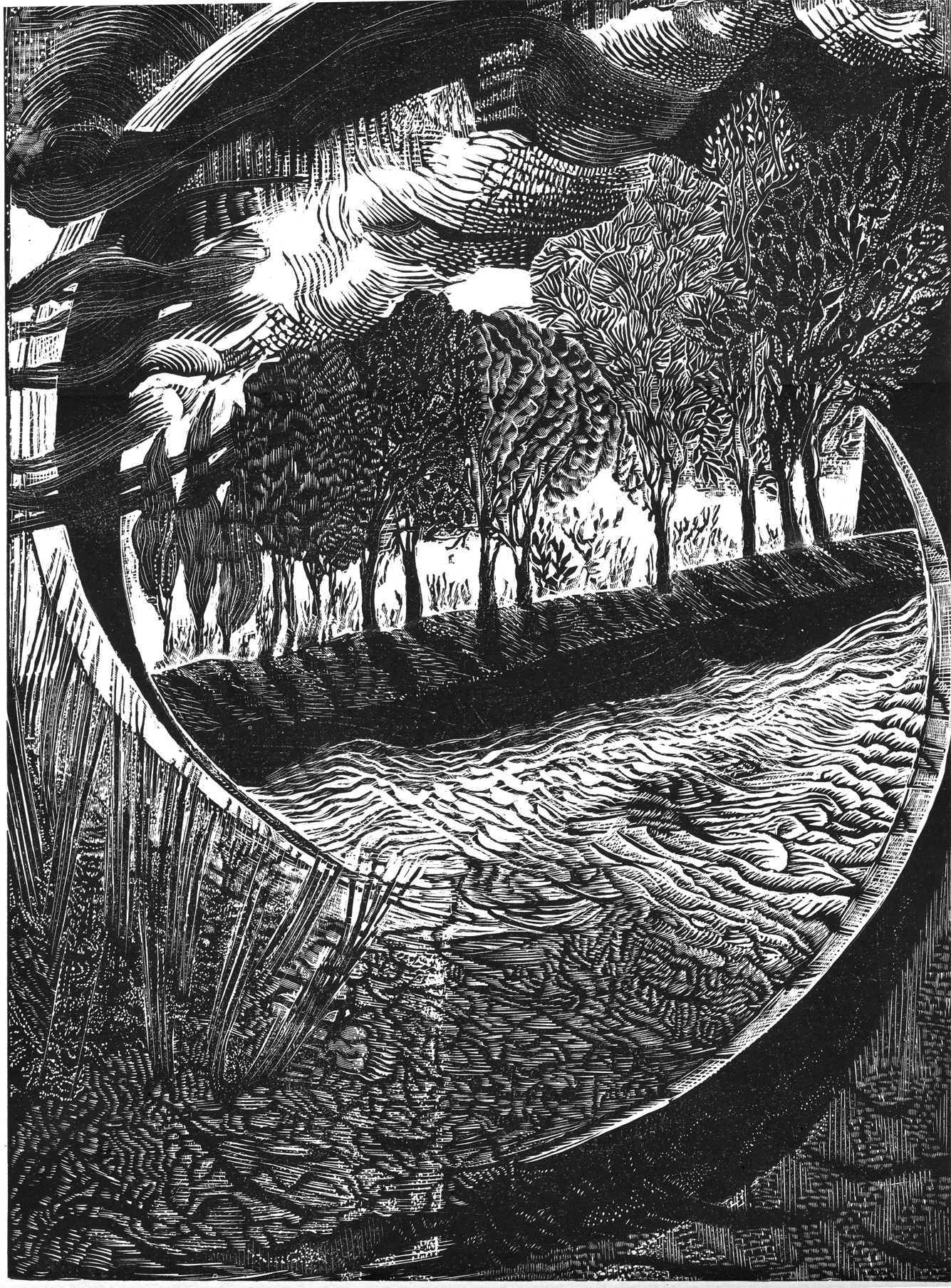

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural. Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”