by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

We tend to think of democracy as a set of governmental institutions. We see it as a political order characterized by open elections, constitutional constraints, the rule of law, freedom of speech, a free press, an independent judiciary, and so on. This makes good sense. These institutions indeed loom large in our political lives.

However, political institutions differ considerably from one purportedly democratic society to the next. Voting procedures, representation schemes, conceptions of free speech, and judicial arrangements are not uniform across societies that are widely regarded as democratic. In some of these countries, voting is required by law and military service is mandatory. In others, these acts are voluntary. Some democratic countries have distinct speech restrictions, others have different and blurrier boundaries. And the ancient Athenians appointed their representatives to the Boule by lot, instead of by vote. Given these variations, how can these societies all be democracies?

This leads to the thought that although certain institutional forms are characteristic of democracies, democracy itself should be identified with the kind of society those institutions realize. We hence can see how two societies with distinct constitutions nevertheless can be democratic.

This prompts the obvious question: What kind of society is a democracy? Read more »

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural.

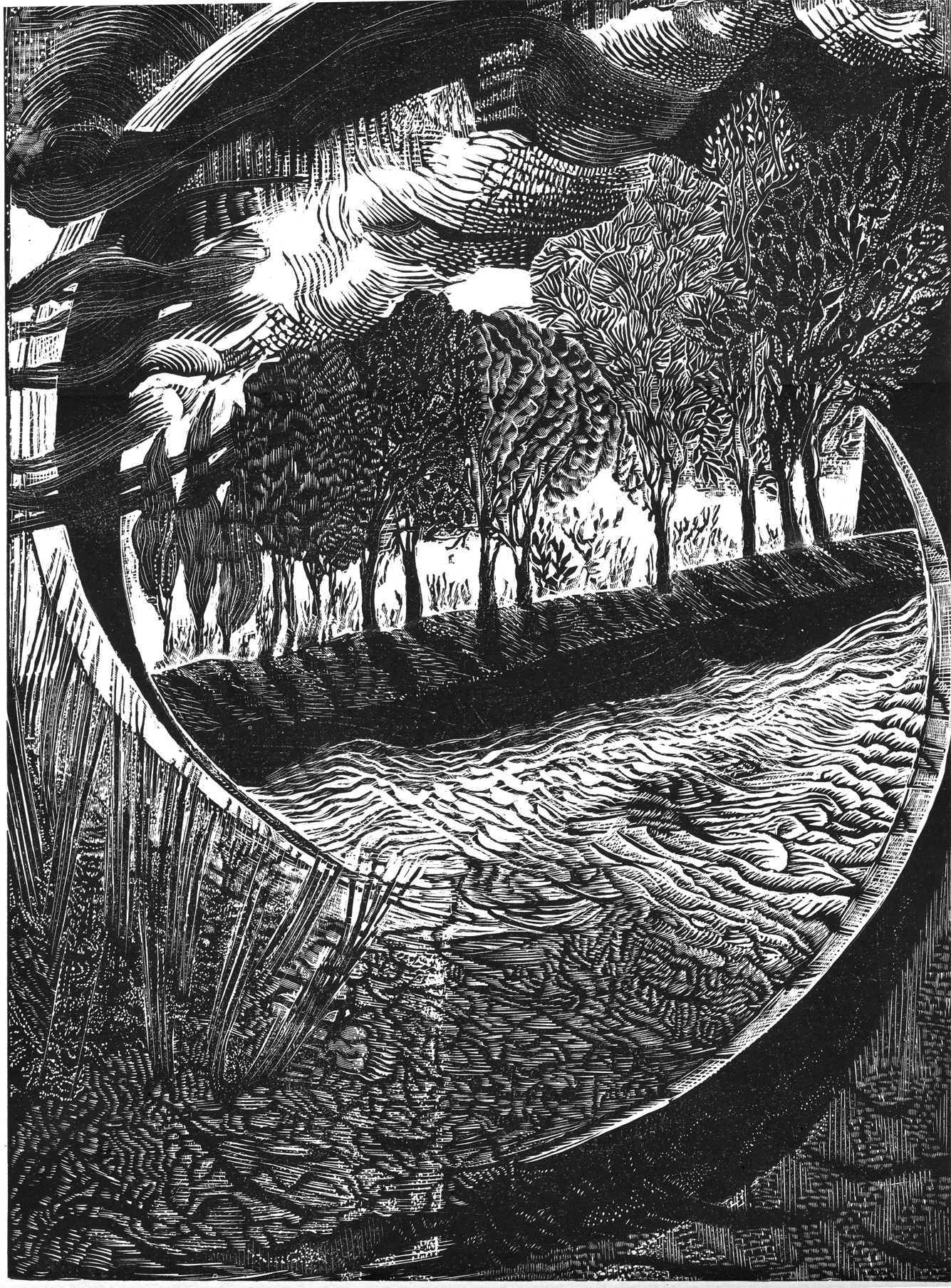

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural. Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

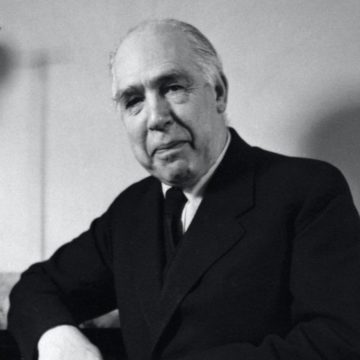

A scar is a shiny place with a story. When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

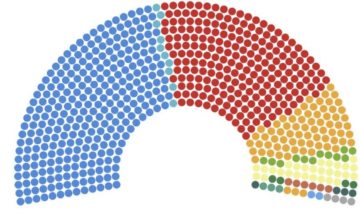

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.