by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

Modern life would be impossible without pet theories. (One of my pet theories is that everyone has pet theories.) How could we make sense of the quotidian horror and cruel contingency of our lives under late capitalism without a little magical thinking? Everyone has a soul mate out there somewhere. There are two kinds of people in the world. The CIA is tracking our Amazon purchases. Black is slimming. One of mine is that during the course of a lifetime, everyone gets one fabulous found item. (Granted, some people may get more than one, but that is rare and clearly bespeaks a karmic debt.) Some may go looking for theirs—like a detectorist unearthing a hoard of Saxon gold—which is not exactly against the rules, but vaguely contravenes the spirit of the theory; most often, however, it comes when you least expect it. I am happy to announce that ten years ago I found mine and so now I can relax. I wish I could say it was a pilgrim shoe buckle or a lost diamond tennis bracelet, but in some ways it was even more valuable—it has, in the ten years since its discovery, afforded countless hours of speculation and amusement. My Found Object is a shopping list.

Medium: Blue ball-point ink on wide-margin 3-ring notebook paper

Location: Shopping cart bottom, Save-On Foods, Cambie Street, Vancouver, BC

Finders: Doctor Waffle and Mr. Waffle, while grocery shopping

Date: 7 August 2010

[Handwriting #1:]

- Milk -> a big one (we can do it)

- Ketchup

- Bread

- Frozen veggies?

- Yogurt (probably strawberry)

- Diet coke

- Juice

- Cheese variety -> the good stuff

- I WILL GET WINE

- Cracker variety

- Salami

elike last time - Some type of cracker spread

- Smoked salmon

- Ceareal ! a good for you kind.

- Peanut butter (REAL) no kraft BS

- Strawberry jam

- Low fat ice cream

- Chicken breasts

- Is the pasta sauce in the fridge any good?

- if not … more sauce.

- Ground beef & pork

- Lets make meet balls? Ill get a recipe

- Croutons & salad dressing

[Handwriting #2, scrawled at top of sheet:]

Sorry Baby got home

at 9pm. Will go

shopping Wednesday

[Handwriting ambiguous, at very bottom of sheet:]

I HAVE $45.00 —

BEANS

Even after countless re-readings and hours of in-depth analysis, this document still has the power to move me deeply. (I am not being facetious.) As soon as my spouse and I finished reading the list multiple times and wiping the tears of laughter from our eyes, we immediately uploaded it to Facebook. Our friends were as transported by the list as we were, and for the next couple of days produced exegesis and commentary worthy of Maimonides. Who are these people? What is their relationship? Why did the list’s original addressee not get to the grocery store (and did he ever)? Why are they so obsessed with eating healthfully, yet also stock their cart with fatty meats and cheeses? What is the meaning of the mysterious addendum BEANS? And perhaps most importantly: how on earth did these people expect to procure the items on this list for $45 in Vancouver, a city where a pint of Ben and Jerry’s costs upward of ten dollars?

The list strikes me as a wonderfully condensed and revealing document of the relationship between Baby (the listmaker) and the laggard who failed to shop.* It is so much more than a list; it is a cri de coeur across an unbreachable gulf. Half of its items are desperate musings on the part of Baby, the mutterings of someone shouldering a burden alone—feeding this small family some reasonably nutritious food on a tight budget—and clearly afraid she will fail at the task. So many poignant question marks! Frozen veggies? Has the pasta sauce gone bad? Shall we make meet balls? In theory these are answerable questions Baby is posing to Laggard, but in reality the list is fraught with peril. There is too much left to chance; these decisions are too important to be made impromptu in the middle of a grocery store aisle; it is a series of traps; probably Strawberry? The varied syntax of the queries, and the fact that they are questions that should be answered before one sits down to make a list, clearly indicate that we’re deep in the slough of self-doubt. We know that Laggard has very little chance of answering Baby’s questions correctly—because Baby herself does not know the answers, and nothing anyone can say or buy in response will satisfy her.

But this situation is not her fault. Baby is on her own here, and her anguish is palpable. Laggard quite simply does not care about good-for-you ceareal, or peanut butter brands, or wasting milk. How do I know? For one thing, Laggard promised to go shopping on Wednesday, yet it was a Saturday when the list was discovered. Could such a document possibly have languished untouched for three solid days in the bottom of a grocery cart? Doubtful. One day perhaps, two tops; at the very least Laggard waited a full 24 hours beyond the promised (already delayed) time before he actually went to the store. Or did he? Perhaps Baby, fed up with eating dry Cap’n Crunch and rank pasta sauce, finally ventured out to do the shopping herself. Maybe she left the crumpled list behind as a final unconscious gesture of pained disgust, then went home and unpacked her salami and cheese varieties and All-Bran and gallon of Pinot Grigio and then changed the locks on the doors. Maybe she bought a small milk.

But my guess is no, because I recognize in Baby bottomless reserves of optimism. “Optimism” is perhaps not the right word, but “desperation” seems too harsh. But in truth it is a kind of desperation, a commonplace kind, the feeling most of us have when shoring up the barricades of domestic tranquility against encroaching terrors, both internal and external. Laggard is a convenient projection, a kind of ghost in the machine (do they ever even see each other in person?) of Baby’s anxiety and dread. Obviously this is now my own projection, but I see Baby as trying to control the uncontrollable, to wrest order from chaos through sheer force of will. I would not be surprised to learn that she—just like me—is addicted to LifeHacker.com and devours any and all articles that promise to rewire your neurocircuitry to create a more organized, creative, happy, and peaceful You. Of course Baby and I do not experience our lives this way on a day-to-day basis. Normally we feel like we have it all under control—we spend a lot of time and energy manufacturing this illusion, after all. It takes a crisis of some kind—a major disruption in routine, a global pandemic, or the experience of sitting down to write a grocery list for someone you suspect is not as interested in your ménage as you are—to reveal the fragility of your defenses and the fungibility of your most cherished assumptions.

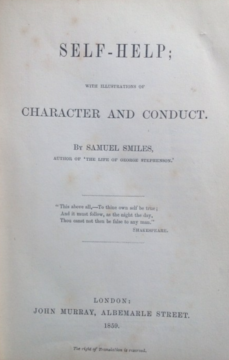

Baby’s cheerful desperation is the legacy not only of her own private history—her family drama, her gender socialization, her class and ethnic background, her educational opportunities, her physical health—but also of a long lineage of institutionalized optimism we can trace back at least as far as Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help, published in 1859. Smiles’s book is a compendium of biographies of successful men who overcame poverty or other adverse circumstances to claw their way into the expanding British Victorian middle class. Smiles’s thesis is essentially that the “spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual…. Whatever is done for men or classes, to a certain extent takes away the stimulus and necessity of doing for themselves, and where men are subjected to over-guidance and over-government, the inevitable tendency is to render them comparatively helpless.” The book is thus a fascinating and contradictory mix of radicalism—upward mobility is possible and your class is not your destiny—and conservatism—but government cannot help and you must pull yourself up by your own bootstraps.

Baby’s cheerful desperation is the legacy not only of her own private history—her family drama, her gender socialization, her class and ethnic background, her educational opportunities, her physical health—but also of a long lineage of institutionalized optimism we can trace back at least as far as Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help, published in 1859. Smiles’s book is a compendium of biographies of successful men who overcame poverty or other adverse circumstances to claw their way into the expanding British Victorian middle class. Smiles’s thesis is essentially that the “spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual…. Whatever is done for men or classes, to a certain extent takes away the stimulus and necessity of doing for themselves, and where men are subjected to over-guidance and over-government, the inevitable tendency is to render them comparatively helpless.” The book is thus a fascinating and contradictory mix of radicalism—upward mobility is possible and your class is not your destiny—and conservatism—but government cannot help and you must pull yourself up by your own bootstraps.

The cheerful persistence that undergirds Smiles’s work is arguably the foundation of the current self-help genre—and the direct ancestor to Baby’s perky optimism. They share a conviction that one can change one’s own circumstances, and that this change can be effected through industry, good habits, thrift, and perseverance. “Self-empowerment” may be the watered-down by-product of the meeting of Smiles’s robust and striving self and the fragmented and divided self of psychoanalysis, but the bare idea that one can improve oneself through acts of will, codified and popularized by Smiles over 150 years ago, is a crucial part of the current self-help ethos. I can easily picture Smiles, Leonard Bast, and Baby all attending the same aspirational TED talk—the Working Men’s College lecture of the new millennium.

In the wonderfully quirky book about self-transformation You Must Change Your Life (the title is from the last line of a Rilke poem), the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk writes: “Wherever one encounters members of the human race, they always show the traits of a being that is condemned to surrealistic effort. Whoever goes in search of humans will find acrobats.” While most of us are awed by extraordinary acts of self-discipline and transcendence, like monks walking across hot coals, ultra-marathon running, or people who lose 300 pounds by eating only dandelion thistle, Sloterdijk’s larger point is that many of us “ordinary” people are also acrobats. Anyone who practices an activity regularly with the aim of improving performance is engaging in “anthropotechnics,” the conviction that human nature can be deliberately manipulated through acts of discipline. For Sloterdijk, the recent popular thesis that Western society is becoming religious again after the hiatus of the Enlightenment is a misunderstanding of the nature of religion itself: what the Judeo-Christian tradition has labeled “religion” is just a segment of the great range of ancient spiritual and philosophical practices whose aim is human self-cultivation.

It would be a gross mischaracterization of the book’s complex, subtle (and long) argument to claim that choosing good-for-you ceareal is akin to Tantric meditation, but since Sloterdijk is not here to defend himself I don’t think there’s any harm in imagining Baby as a cutting-edge anthropotechnician. Why not grant her attempts to follow a healthful and regular routine a measure of respect? Why not accord her dignity? After dozens and dozens of re-readings of this list I feel I have come to know her a little bit, and it seems like the least I can do in return for the hours of delight and wonder her shopping list has given me.

Baby’s anxious self-improvement regime at the time—as that of so many of us—took the form of an obsession with healthy eating. Thus the infantile unconscious bargain: if I put into my mouth only things that are good for me, then I will never die. But directives from the Id and from Thanatos lard the bland surface of Baby’s idealized diet: will the fat-free ice cream, Diet Coke, and good-for-you ceareal offset the salami(e), cheese, ground beef and pork? (Assuming of course that aspartame, glutinous grains, and artificial fats are even good for you, truisms of yore that have come under increasing attack in the past few years.)

And no wonder these decisions are anxiety-provoking—so much of our hope resides in their outcome. As Ernst Bloch argued 60 years ago in The Principle of Hope, the “utopian impulse” can take a myriad of forms beyond the writing of novels about ideal societies. For Bloch, the utopian was a capacious category that included daydreams, myths, circuses and dance performances, fantasies of travel, the promises of religion, fairy tales, and alchemy: all dreams of a better life. (Or, for example, elaborate “clean eating” plans that cut out gluten, sugar, alcohol, dairy, or meat in the hopes of resetting one’s digestive system and thus creating a Brand New You.) Yet Bloch also believed that all utopian impulses contain an “anticipatory consciousness” that is the driving force behind actual social change. Even compensatory daydreams and petty selfish longings have a kernel of the good stuff in them; there is an anticipatory element in all utopian impulses, even the most private and solipsistic.

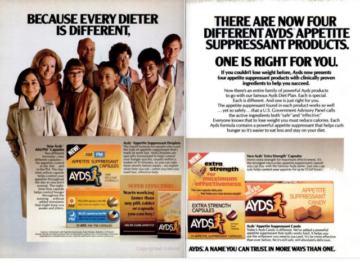

When I was growing up my mother was a chain smoker and a serial dieter. While she never really cared that much about the smoking—it was always at my father’s insistence that she made any of her failed attempts at quitting—her intense vanity meant she did care about the weight part. Since she was a talented athlete she never got terribly heavy, but she always complained about never returning to her “pre-baby” weight after giving birth to me and my sister in close succession.  The diets came in nearly as close succession: Slim-Fast, grapefruit, Dexatrim and Ayds, and later South Beach, Atkins, and gluten-free. As is the case for every single human being on planet Earth, the diets would work for a while, she’d drop 15 or 20 pounds, and then within a year gain it all back plus a few extra. I thought she was beautiful.

The diets came in nearly as close succession: Slim-Fast, grapefruit, Dexatrim and Ayds, and later South Beach, Atkins, and gluten-free. As is the case for every single human being on planet Earth, the diets would work for a while, she’d drop 15 or 20 pounds, and then within a year gain it all back plus a few extra. I thought she was beautiful.

For a number of years we had a little ritual: when my sister and I accompanied our mother on her errands, which always ended at Mackie’s Drug Store, we would each get a Star Bar candy bar as a treat. It was never stated explicitly, but somehow we understood that we were not to eat them in front of our father, but to make sure they were gone before he came home. Later my mother started buying them by the box and squirrelling them away in the house; it was at this point that my sister and I were no longer invited to share in the hoard. Right around this time she started locking herself in the bathroom for most of the day, to smoke “secretly” and read romance novels.

Thanks to the sixty years of smoking, my mother died of advanced vascular dementia brought on by hundreds of mini-strokes. She never did much of anything with her life, which I know sounds harsh. I’m not suggesting that in order to be a fulfilled human being she must have finished college or had a career or even done anything other than smoke and read and eat candy bars and play tennis. But if she had done these things joyfully and unapologetically and with brio and verve, that would have been a good life, I think. Instead she hid herself away and waited for time to pass. She never engaged in rugged self-help, life-hacking, or anthropotechnics, and now it’s too late. She spent her final days wheeling around the halls of her nursing home greeting everyone as if they were long-lost family. She made everyone smile. Perhaps this was a good life.

My mother’s shopping lists were written on a small-sized yellow legal pad that she kept by the phone in the kitchen. For a while she flirted with special “Grocery List” pads where you could tick off boxes next to items like “Hamburger” and “Mayonnaise,” but I imagine she found the suggested items too generic and eventually returned to the yellow pads. She always wrote in cursive, and her handwriting was slanted and spidery, but very clear. The lists were the public face of her shopping expeditions: Powdered Milk, White Bread, Spaghetti, Frozen Peas, Skippy Peanut Butter. She must have kept the secret version (candy bars, cigarettes, Harlequin romances) in her head. She was on her own, just like Baby, but her aloneness was more profound; there was no Laggard at home she could even pretend might do the shopping for her, just my dad arriving home from his day at work, loosening his tie and fixing a Scotch on the rocks. Baby might be slightly desperate, but she is putting it all out there: there is nothing secret about her list, and her desperation is more about keeping a promise to herself than about trying to get through the next lonely day.

Perhaps this is why I love the list so much. If it’s an anguished yelp, a least it’s a hopeful one that imagines there just might be another coeur out there to hear its cri. Baby’s world is one in which it’s perfectly acceptable to make things up as you go along, to decide on the fly what kind of yogurt to get and just kind of hope you have enough money to buy all the things you need. Who knows if she and Laggard managed to get all that food for $45. Who knows if they finished their large milk. Who—who on earth—knows what “BEANS” means. She is an anthropotechnician for sure, but a pretty loose and improvisational one—more like a MacGyver than a Da Vinci. I like to think of her out there making good decisions in the grocery aisles. I like to think she trusts the world.

* Why is it so obvious that Baby is a woman and Laggard is a man? The particular quality of beseechment on the part of Baby and the insouciance with which Laggard announces that he has procured nothing for them strike me as very gendered. The cliché is that straight women implore their men to care about domesticity and the men resist. Obviously Baby and Laggard could also be gay or genderqueer or nonbinary. But whatever their sex or gender identification, it seems clear—if Judith Butler and Chuck Lorre have taught me anything over the years—that Baby and Laggard are at the very least inhabiting the roles of Feminine and Masculine respectively.