by Charlie Huenemann

Over years of teaching philosophy, I have observed that people fall into two groups with regard to the Biggest Question. The Biggest Question is one that is so big it is hard to fit into words, but here goes: When everything that can be explained has been explained, when we know the truths of physics and brains and psychology and social interactions and so on and so forth, will there still be anything worth wondering about? I am assuming the “wonder” here is a philosophical wonder, not the sort of wonder over whatever happened to my old pocket knife or whatever. It’s the sort of wonder that has a “why-is-there-something-rather-than-nothing” flavor to it. It’s the sort of wonder that doesn’t go away no matter how much is explained.

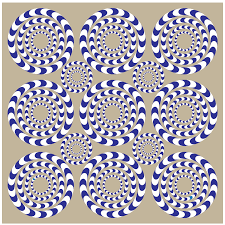

Some people think that on that sunny day when everything that can be explained has been explained, well then, that will be that. We will understand why things have happened, and how we came to exist, and what we should do if we want to be healthy and happy, and why works of art move us as they do. It’s not that such people are in any way shallow or unimaginative or tone deaf. They are open to the most wonderful experiences of life, along with the most heart-wrenching and most tragic. It’s just that they think these experiences can be explained and understood in all their glory through that explanation. If there is anything “left over” — some stubborn bit of incredulous wonder we just can’t shake — then that too will be explained through some feature of human psychology, like the way those patterns still seem to swirl in a static optical illusion even when you know the trickery behind it. The feeling that there is a Mystery can itself be explained as an illusory sort of feeling, an accidental by-product of the cognitive engine we happen to think with.

But other people think that the Mystery is not an illusion or accident, and that there still would be something worthy of genuine philosophical wonder even when the grand explainers have completed their grand task. Maybe the Mystery is worthy of some kind of worship or spiritual reverence. Maybe it can be reflected in a poem or in music or in a painting, or even in a shared and silent moment with friends. Maybe it is exactly what remains when all explaining is done — as Wittgenstein the Sage once wrote, “Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is”. In his terms, the Mystery is precisely that of which we must remain silent, simply because no amount of talking will capture it. These people would say that the first group of people are the ones with the illusion: namely, the illusion that what can’t be explained isn’t real.

Whatever exactly “the Mystery” is, it’s a big deal, meaning that the Mystery is not merely some odd fact having to do with the spin of electrons or the metabolism of starfish, but something around which all value turns. It is the universe’s third rail, the thing that can’t be touched that somehow powers the value of the whole shebang, the thing that keeps Sisyphus happy and makes poets want to keep writing and that holds the attention of the mystic. It need not be religious, but it has many of the attributes people typically tag onto divine entities: it lies beyond our comprehension, it imparts value to certain things, it is an appropriate focus for one’s heart, and so on.

I don’t know which group I fall into — it seems to vary depending on what I happen to be reading at the time, which I guess probably puts me into the first group by default — but I certainly get where the second group is coming from, and it is only because of this that I can find anything of interest in Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard of course is the Great Dane who kept going on and on about Abraham. Kierkegaard (or at least his invented persona Johannes de Silentio) couldn’t get over the fact that when Jehovah the Infinite Absolute Father told Abraham to go do the Absolutely Forbidden by murdering his own child Isaac through which Abraham was to have countless descendants, to sacrifice everything that made Abraham’s life worth living is order to preserve everything that made Abraham’s life worth living, Abraham woke up early the next morning, saddled his ass, and made his way to the mountain to do the thing. Abraham just went about his business when thrust into the middle of the totally Unthinkable. How does one do that?, John the Silent wondered aloud. How do you just go about your business when in the presence of the Thunderingly Impossible?

The absurdity of Abraham’s position should be accessible to any of our type-2 people, the true believers in the Mystery. For here they are — no, let us say here you are — in the middle of existence, with the biggest and most important thing hanging around your neck, the thing which no amount of talking will ever begin to describe, the thing over which poets and mystics sweat blood, the thing Beethoven heard when he was deaf. And here you are shopping, or stuck in traffic, or chopping vegetables, or saddling your ass to head over to the mountain. Is this any sort of right way to live with a Mystery? Kierkegaard found Abraham unthinkable, but we might just as well find all of us unthinkable, at least all of us who believe that at the bottom of it all lies in unsayable Truth that makes the universe something other than an accident. How are any of us supposed to get any work done under these conditions?!

The first group of people, let us readily admit, can be perfectly consistent on this score. The appearance of wonder and mystery can be enjoyable and fruitful and can even inspire us to action, and so it should be sampled and savored. But one shouldn’t take the mystery too seriously; it will one day be explained, and so it should not make us worry through the night about whether our magnificent cognitive engines will be sufficient unto the task. Enjoy what we can, help suffering to go away, be a good neighbor, try to understand why the stars shine as they do, get some exercise, and call it a life. There is no difficulty here, or at least no difficulty that is impossible to address in a thoughtful way.

It’s the other group that has the bigger problem. If one believes in the Mystery, and hangs all value upon it, but then treats it like something to be visited every few weeks or to be mindful of for twenty minutes each day, and otherwise goes about the ordinary motions of everyday life, then one is as astonishing as was Abraham to Kierkegaard. Though, to be fair, what else is one supposed to do? Invent a dozen pseudonyms and write about it? Dance at an airport and sell pencils? Put on a hairshirt and talk to the birds? Every response that can be imagined seems no less absurd than the ones we ordinarily adopt. So the Mysterians are stuck in a difficult circumstance: dressed up in all that Infinite, and nowhere to go. Kierkegaard — well, actually this time it was Johannes Climacus — suggested that we should embrace objective uncertainty with the passion of the infinite. Well: okay. I don’t know about you, but I find it hard to summon the passion of the infinite when I’m in line at Starbucks. A failure of imagination on my part, no doubt.

This, I suspect, is why we smoke.