by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

Modern life would be impossible without pet theories. (One of my pet theories is that everyone has pet theories.) How could we make sense of the quotidian horror and cruel contingency of our lives under late capitalism without a little magical thinking? Everyone has a soul mate out there somewhere. There are two kinds of people in the world. The CIA is tracking our Amazon purchases. Black is slimming. One of mine is that during the course of a lifetime, everyone gets one fabulous found item. (Granted, some people may get more than one, but that is rare and clearly bespeaks a karmic debt.) Some may go looking for theirs—like a detectorist unearthing a hoard of Saxon gold—which is not exactly against the rules, but vaguely contravenes the spirit of the theory; most often, however, it comes when you least expect it. I am happy to announce that ten years ago I found mine and so now I can relax. I wish I could say it was a pilgrim shoe buckle or a lost diamond tennis bracelet, but in some ways it was even more valuable—it has, in the ten years since its discovery, afforded countless hours of speculation and amusement. My Found Object is a shopping list.

Medium: Blue ball-point ink on wide-margin 3-ring notebook paper

Location: Shopping cart bottom, Save-On Foods, Cambie Street, Vancouver, BC

Finders: Doctor Waffle and Mr. Waffle, while grocery shopping

Date: 7 August 2010

[Handwriting #1:]

- Milk -> a big one (we can do it)

- Ketchup

- Bread

- Frozen veggies?

- Yogurt (probably strawberry)

- Diet coke

- Juice

- Cheese variety -> the good stuff

- I WILL GET WINE

- Cracker variety

- Salami

e like last time - Some type of cracker spread

- Smoked salmon

- Ceareal ! a good for you kind.

- Peanut butter (REAL) no kraft BS

- Strawberry jam

- Low fat ice cream

- Chicken breasts

- Is the pasta sauce in the fridge any good?

- if not … more sauce.

- Ground beef & pork

- Lets make meet balls? Ill get a recipe

- Croutons & salad dressing

[Handwriting #2, scrawled at top of sheet:]

Sorry Baby got home

at 9pm. Will go

shopping Wednesday

[Handwriting ambiguous, at very bottom of sheet:]

I HAVE $45.00 —

BEANS

Even after countless re-readings and hours of in-depth analysis, this document still has the power to move me deeply. (I am not being facetious.) As soon as my spouse and I finished reading the list multiple times and wiping the tears of laughter from our eyes, we immediately uploaded it to Facebook. Our friends were as transported by the list as we were, and for the next couple of days produced exegesis and commentary worthy of Maimonides. Who are these people? What is their relationship? Why did the list’s original addressee not get to the grocery store (and did he ever)? Why are they so obsessed with eating healthfully, yet also stock their cart with fatty meats and cheeses? What is the meaning of the mysterious addendum BEANS? And perhaps most importantly: how on earth did these people expect to procure the items on this list for $45 in Vancouver, a city where a pint of Ben and Jerry’s costs upward of ten dollars? Read more »

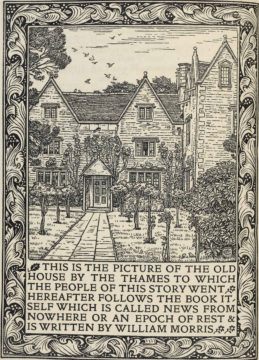

The recent show

The recent show  What does the word “utopia” mean to the battle-scarred denizens of the twenty-first century? A shockingly unscientific survey of the nine or ten people I buttonholed last week suggests that the key connotations of the word are: ideal, perfect, imaginary, unrealistic, and unattainable. I’ve arranged these terms purposefully in that order, so that they imply not a static and fixed definition but rather a narrative arc, a falling away from hope into disappointment: all of the people I spoke to (students and colleagues at the large Southern state-flagship university where I teach, so a fair cross-section of ages, races, ethnicities, and genders) firmly believed that the word “utopia” denotes an unrealistic or quixotic goal. It’s not my thesis here that disappointment is the necessary fate of any utopian project, but it might be a provisional thesis that most people living in Western cultures today think that it is.

What does the word “utopia” mean to the battle-scarred denizens of the twenty-first century? A shockingly unscientific survey of the nine or ten people I buttonholed last week suggests that the key connotations of the word are: ideal, perfect, imaginary, unrealistic, and unattainable. I’ve arranged these terms purposefully in that order, so that they imply not a static and fixed definition but rather a narrative arc, a falling away from hope into disappointment: all of the people I spoke to (students and colleagues at the large Southern state-flagship university where I teach, so a fair cross-section of ages, races, ethnicities, and genders) firmly believed that the word “utopia” denotes an unrealistic or quixotic goal. It’s not my thesis here that disappointment is the necessary fate of any utopian project, but it might be a provisional thesis that most people living in Western cultures today think that it is.