Lush Misunderstanding

—of an interview with Jane Goodall

_____________________________________

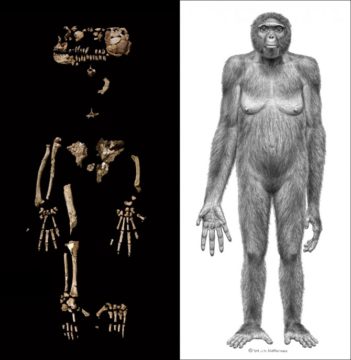

life from dying comes

—life after life:

a ballet of treed chimps,

a great defining roar,

a thin thread lost

where are you, father?

(a name I never called you,

I called you, Dad)

yet there it is: father

half-ground of my issue,

half-ground of my being,

chimps throw rocks into a waterfall

to watch them drop, to hear them splash

they sit watching stones and water fall

what is this, this dead tree

with its skin of moss and mushrooms

pushing up and out, this light-giving

thing overhead in its brilliant cape of blue,

this light, splashing, falling down,

this hard and heavy thing

I heave into empty-what

to watch it fall and vanish

into a gleaming mirror-hole

in the ground?

life from death

where are you, father?

the forest makes no demands on me,

says Jane,

it doesn’t care that I’m here

what is this distance,

this insistent swath of lush

misunderstanding?

Jim Culleny, 12/30/20

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. February, 2022.

Why do I have to help?

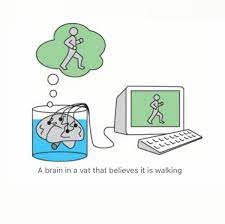

Why do I have to help? Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

In late January the United States Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a draft discussion of its COVID-prompted public health bill titled, “Prepare for and Respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging New Threats, and Pandemics Act” (

In late January the United States Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a draft discussion of its COVID-prompted public health bill titled, “Prepare for and Respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging New Threats, and Pandemics Act” ( Soon K.N.Raj gave up his Vice-Chancellorship and moved to his home state, Kerala, and started a new institution, Center for Development Studies (CDS). He tried to lure me (and Kalpana) to join the faculty there, and even offered to get us land on which he’d persuade his friend Laurie Baker (a resident British-Quaker architect) to build us a low-cost, energy-efficient beautiful house (like his own). At CDS, he not merely provided intellectual leadership, he was the pater-familias for the group. After a whole day of teaching and seminars, in the evening he’d visit his colleagues’ homes, try to solve their multifarious domestic problems, while his wife, Sarsamma, will minister to their sundry medical needs. Once driving me to the airport, when I was all praise for the young institution and the community he was in the process of building, he asked me if I had any word of criticism. I told him it was too much of a “Hindu undivided family” for my taste. Raj corrected me and said it was not “Hindu” — he did not seem to mind the “undivided family” part.

Soon K.N.Raj gave up his Vice-Chancellorship and moved to his home state, Kerala, and started a new institution, Center for Development Studies (CDS). He tried to lure me (and Kalpana) to join the faculty there, and even offered to get us land on which he’d persuade his friend Laurie Baker (a resident British-Quaker architect) to build us a low-cost, energy-efficient beautiful house (like his own). At CDS, he not merely provided intellectual leadership, he was the pater-familias for the group. After a whole day of teaching and seminars, in the evening he’d visit his colleagues’ homes, try to solve their multifarious domestic problems, while his wife, Sarsamma, will minister to their sundry medical needs. Once driving me to the airport, when I was all praise for the young institution and the community he was in the process of building, he asked me if I had any word of criticism. I told him it was too much of a “Hindu undivided family” for my taste. Raj corrected me and said it was not “Hindu” — he did not seem to mind the “undivided family” part.

Sughra Raza. Kaamdani, Approaching Santiago, Chile, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Kaamdani, Approaching Santiago, Chile, 2017.

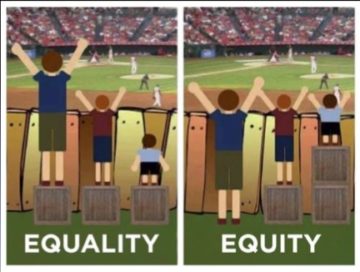

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.

In the game of chess, there are dramatic moves such as when a knight puts the king in check while at the same time attacking the queen from the same square. Such a move is called a fork, and it’s always a delicious feeling to watch your opponent purse his lips and shake his head when you manage a good fork. The most dramatic move is obviously checkmate, when you capture the king, hide your delight, and put the pieces back in the box. But getting to either the fork or checkmate involves what’s known in chess as positioning, and for the masters, often involves quiet moves long in advance of the victory.