by John Allen Paulos

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The group, which was founded by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais in Paris in 1960 and is still somewhat active, searches for novel literary structures that arise from the imposition of mathematical constraints and methods of systematically transforming texts. Theophile Gautier has written that the rigidity of the constraints ensures the durability of the work, whether in poetry, art, or sculpture. More graphically, Queneau described the group’s activity as “rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape.”

Simple combinatorics plays a role in many of Oulipo’s efforts. Queneau’s 100 Trillion Sonnets is a prime example of its approach to literature. The work consists of just ten sonnets, one on each page of a ten-page booklet. (Note that the 14-line sonnet is itself a product of an artificial restriction.) The pages of the booklet are cut so that each of the 14 lines of the ten sonnets can be turned separately. Thus, we can combine any of the ten first lines with any of the ten second lines, which results in 102 or 100 different pairs of opening lines. Any of these 102 possibilities may in turn be combined with any of the ten third lines to yield 103 or 1,000 possible sets of three lines. Iterating this procedure and utilizing the multiplication principle, we conclude that there are 1014 possible sonnets. Queneau claimed that they all made sense, although it’s safe to say that the claim will never be verified, since there are probably more texts in these 1014 different sonnets than in all the rest of the world’s literature. (His claim could, of course, be easily refuted.)

Incidentally, years ago I was inspired by 100 Trillion Sonnets to patent a variant of a Rubik cube that I called About Face. Each of the cube’s six sides pictured a face that remained a face when any of the sides were subjected to a certain class of rotations. The result was a gazillion possible mugshots. Alas, it never went anywhere. Read more »

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

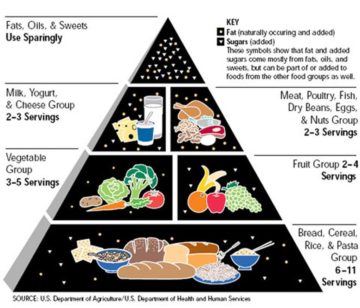

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack.

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack. It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends.

It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends. The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like

The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like  The United States has always faced a fundamental tension. On one side are those who champion, enforce, and/or profit from hierarchies of power: white supremacist racism, sexist patriarchy, Christian fundamentalism, and capital concentrations chief among them. Arrayed against these hierarchies of power are people who promote and work for racial equality, gender and sexual equality, cultural tolerance, the amelioration of poverty, and genuine freedom both for and from religious beliefs and practices.

The United States has always faced a fundamental tension. On one side are those who champion, enforce, and/or profit from hierarchies of power: white supremacist racism, sexist patriarchy, Christian fundamentalism, and capital concentrations chief among them. Arrayed against these hierarchies of power are people who promote and work for racial equality, gender and sexual equality, cultural tolerance, the amelioration of poverty, and genuine freedom both for and from religious beliefs and practices.