by Mark Harvey

When I am dead, then bury me

In my beloved Ukraine,

My tomb upon a grave mound high

Amid the spreading plain

—Taras Shevchenko

If you didn’t know who Vladimir Putin was and you ran into him in, say, Dayton, Ohio, you might take him to be the owner of a small family-run mortuary. With his pallid complexion, dour bearing, and ordinary features, he has all the makings of a good mortician who could feign enough concern and show enough solemnity to upsell you on a walnut coffin for a distant aunt.

An impressive figure, the man does not cut. He is short, pale, balding, and lacking in a good Soviet chin. It’s been said that great leaders need to have enough charisma to rattle the furniture when they walk into a room. But Putin has a reptilian aura, only missing the scales and a tail that can grow back when the original is torn off while desperately escaping a raptor.

It makes you wonder what sort of knots Mother Russia has tied herself in to choose such a demonic milquetoast figure to rule such a glorious land. What we know about the Russian people is that they are gifted beyond measure in literature, music, poetry, drama, dance, sports, the hard sciences, and of course, chess. But with their otherworldly gifts they seem to have a self-destructive element manifested in a revolving door of imprisoning their heroes in their gulags, choosing despotic leaders, high rates of alcoholism, and a skepticism only immune to world class agitprop.

So to see such a great land ruled by such a small, diminished but cruel man is painful. And with his last gasp at greatness at age 69, amassing 200,000 troops on the border of Ukraine, sending warships into the Black Sea off the Crimean Peninsula, and then attacking Ukraine beneath an embarrassing interpretation of its national history, has us all hoping the man meets an unhappy end. (Even those of us who keep trying unsuccessfully to practice universal compassion).

Commenting on the Ukraine crisis, a wag on TikTok said, “Congratulations, in just two weeks we’ve all gone from being expert virologists to expert geopolitical analysts.” Some truth to that. The geopolitics of the relationship between Ukraine and Russia have those who have dedicated their entire careers to the subject arguing over the current war. Nevertheless, as expertly diagnosing the spread of the COVID virus is getting dull to those of us who have never even touched an electron microscope, let’s wade into Eurasian politics.

In the reading I’ve done about Russian history, there always emerges a mysterious figure from the 16th century called Ivan the Terrible. He was really Ivan IV and the czar of Russia from 1547 to 1584. Ivan the Terrible may be a poor translation as in Russian he is called Ivan Grozny, and the word grozny in Russian is closer to formidable, redoubtable, and menacing. And to many Russians, Ivan’s terrible or grozny qualities were something to be admired, not abhorred. It gave him the power needed to rule such a vast land. The true history of Ivan the Terrible has given scholars lots to write about, mostly because there is so little written about him by those with a first-hand account. Thus some of his reputation comes from folklore.

Ivan managed to fit a lot of bloody wars into his life and it’s hard to imagine he had much family time with his string of six wives. His wars included the Polish-Lithuania War, the sacking of Novgorod, the Conquest of Kazan, the Russo-Turkish War, the Livonian War, and the Conquest of Siberia. That is a partial list. And his style of warfare was brutal. During the sacking of Novgorod, in addition to killing and torturing thousands of inhabitants, he tied men, women and children accused of treason to sleighs and ran the sleighs into the icy waters of the Volkhov River to drown them.

Ivan also organized what was considered Russia’s first version of a political police force in what was called the Oprichniki. The Oprichniki was a group of carefully selected men to serve as Ivan’s personal police regiment. They numbered around 6,000 men at its peak, dressed entirely in black, rode black horses, and used the broom and dog’s head as their symbols. The broom symbolized sweeping away of traitors and the dog’s head symbolized nipping at the heels of enemies. If only the Oprichniki were as gentle as rabid dogs. They were known for relentless days of torturing enemies, rapes, whippings, and mutilations. Some suggest the Oprichniki were the ancestors of the KGB.

Ivan the Terrible’s style of ruling seems to have set the pattern for Russia over the last 400 years including today’s wannabe czar, Vladimir Putin. You can hopscotch through Russian history and almost anywhere you land you’ll meet strange, cruel, crazy, and capricious rulers.

Take the niece of Peter the Great, Anna Ionnovna, who ruled Russia from 1730 to 1740. Known as Anna of Russia, she was disappointed in love when her hard-drinking husband died shortly after their wedding. She was desperate to marry again but never managed to land a suitor. For reasons beyond my reading, she took a terrible disliking to one Prince Mikhail and forced him to marry an unattractive woman named Avdotya Ivanovna. She then built them an elaborate palace 30 feet high made entirely of ice. It included an ice bed, ice pillows, and an ice clock. Anna forced the newly betrothed to spend their wedding night in the ice castle entirely naked in the middle of the brutal Russian winter. The couple somehow survived. It’s rumored the bride traded a pearl necklace for a coat with one of the guards.

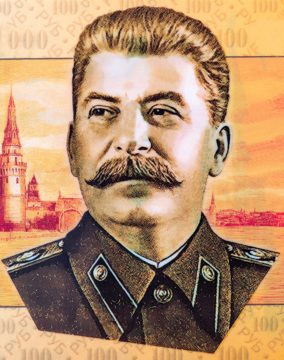

Despite the Russian Revolution and the many Soviet slogans about brotherhood and equality, the cruel tendencies of Ivan the Terrible survived well into the 20th century. In a conversation with Sergei Eisenstein, the film director who made a biopic about Ivan the Terrible, Joseph Stalin said, “When Ivan the Terrible had someone executed, he would spend a long time in repentance and prayer. God was a hindrance to him in this respect. He should have been more decisive.”

None of the “He could not tell a lie” mythology surrounding George Washington or folksy quotes like President Gerald Ford’s “Tell the truth, work hard, and come to dinner on time” for Joseph Stalin. No, his problem with Ivan the Terrible was that he just wasn’t quite terrible enough. And if Stalin’s cruelty didn’t have all the baroque torturing of his predecessors, he certainly killed more of his own countrymen than probably any Russian leader. Impossible to know the exact number of Russians killed by Stalin (through direct executions, starvation, or gulags), but scholars agree it was in the millions.

Stalin was particularly hard on Ukraine. Between 1932 and 1933, close to 4 million Ukrainians died from a terrible famine called the Holdomor, meaning death by famine in Russian. With its rich black earth, seasons of summer wheat and winter wheat, Ukraine never should have seen mass starvation.

There is still debate among scholars as to whether the famine was caused by Stalin’s sheer ineptitude managing the agricultural economy or intentionally done out of his hatred of Ukrainians. Regardless, Stalin, like Putin, couldn’t stand the idea of an independent Ukraine and did his utmost to kill any movement toward independence from the Soviet Union. Whether through summary executions, imprisonment, or torture, he brutalized hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian writers, politicians, priests, and intellectuals if they ever strayed whatsoever from the Soviet agitprop.

Putin has quietly revived Stalin in Russia and compared him to Oliver Cromwell, the English general who lead the charge in not one but two civil wars. That he chose Cromwell, one of the most brutal generals in England’s history, for a favorable comparison is telling. Writing in the Washington Post, Peter Rutland calls Putin a Stalin-lite.

There is great irony (and perhaps hope) in the massive protests against Putin’s invasion of Ukraine that were held in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Tbilisi is only about 40 miles from the town of Gori, where Stalin was born. Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, thousands gathered near the parliament buildings in Tbilisi to denounce Putin and his war. Of course it hasn’t been long since Georgia and Russia had their own little war when fighting between the two nations broke out in August of 2008. That war, though explained by Russia with painfully contorted justification, sure looked like revanchism.

Ukraine has such a long, complex history, that to get some basic understanding of its internal politics and its role on the international scale would take a few Ph.Ds. worth of study. Today we simplify its role as the gateway between east and west, the interface between the old Soviet Union and the modern European Union. To the west, it is characterized as a nation clamoring for freedom and independence and a modern way of life.

But if you dip into Ukraine’s history, you find it has a long, complicated past that does indeed involve the intersection of east and west, the old and the new. Over the more than thousand years of its existence, what we now call Ukraine has seen pre-Roman Greek colonies on the Crimea, hundreds of years of Viking domination beginning in the 9th century, Mongol hoards in the 13th century, the Cossacks in the 15th century, and many more groups all trading goods, fighting wars, pushing their religion, interbreeding, and molding the language. I suppose you don’t need to know of long Viking campaigns through Ukraine territory down to Turkey, of trading Crimean slaves on the Ottoman market, or the Slavic connections to its neighbors to form opinions about the war today, but it sure does make the area more intriguing and lifts up the conversation beyond our usual American simplification of far-off conflicts. Simplifications that often center around the question, How will this affect my American lifestyle? To wit, what will the war do to gas prices?

As Anne Applebaum points out in Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, the geography of the country offers few natural defenses. To the east is a wide-open steppe and to the northwest are gentle woods and pastures and fields. There are no rivers to separate it from bordering nations. Besides the Carpathian mountains to the southwest, the country is not defined by clear topography. The very word Ukraine means borderland in both Polish and Russian. Applebaum suggests that despite having distinct customs, culture, language, music, food, etc., its open geography has made it difficult to form an independent nation—well into the 20th century.

Given Putin’s justification for the invasion—to de-Nazify Ukraine—it’s safe to say his propaganda has nothing to do with his real motive which is crushing its independence. After all, the heroic leader of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish himself and a few days ago the Russians bombed Babi Yar, the site which is now a memorial of where German Nazis killed 33,000 Jews over two days in September of 1941.

As he approaches 70, Putin must be considering his place in history and compared to some of his predecessors, his legacy appears to be that of a small, frustrated man– Vladimir the Petit, itching to be a Peter the Great. And if Peter the Great wasn’t a good man, he was nevertheless a Great man if you consider his accomplishments in the 17th and 18th centuries. He industrialized Russia, making it the greatest iron producer in the world, built the modern Russian navy, founded St. Petersburg, completely redesigned Russian education, created the Russian Academy of Sciences, and won two major wars, greatly adding to Russia’s territories and influence.

And Putin? A botched war in Chechnya and Georgia, the grotesque accumulation of wealth for himself and his oligarchical friends, all those cringe-worthy macho stunts riding horses without a shirt, staged hockey games, and stiff judo rolls. As one commenter in the Washington Post wrote recently, “…he thinks of himself as a latter-day Ivan the Terrible, but the Russians have realized he is Czar Nicholas with a Breitling watch….”

There is a YouTube video of Putin singing his own version of Blueberry Hill (the song made famous by Fats Domino) at a charity dinner held in St. Petersburg in 2010. As he walks out to the microphone to sing, he looks painfully uncomfortable like some overworked accountant at a karaoke bar, prodded to sing without enough vodka in his system. He pronounces the words hill and thrill and still with the Russian sound of scraping a word across the top of the mouth. Various luminaries such Goldie Hawn, Kevin Costner, and Gerard Depardieu attending the event clap along with delight. As the song progresses, Putin appears to relax a tenth of a notch and enjoy himself. With his diminutive size, light-background singing voice, and slightly effeminate manner, it’s easy to imagine him in another lifetime starring in his own televised children’s show—a St. Petersburg version of Mr. Rogers.

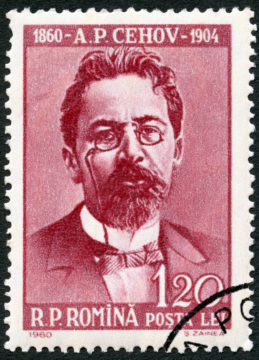

In Anton Chekov’s play The Seagull, the young playwright Treplieff falls madly in love with the aspiring actress Nina, who stars in one of his plays. But Nina is infatuated with the novelist Trigorin and has no use for Treplieff.

Treplieff is also suffering as a playwright for what he considers the lack of respect given him by his mother’s famous and accomplished friends. He says, “What could be more intolerable and foolish than my position, Uncle, when I find myself the only nonentity among a crowd of her guests, all celebrated authors and artists?”

In act II, Treplieff kills a gull with a shotgun and lays it at Nina’s feet. She is horrified, picks up the gull and says to Treplieff, “What is happening to you?”

After threatening suicide for being spurned, he responds, “You have failed me; your look is cold; you do not like to have me near you.”

He continues, “I have burnt the manuscript to the last page. Oh, if you could only fathom my unhappiness! Your estrangement is to me terrible, incredible; it is as if I had suddenly waked to find this lake dried up and sunk into the earth.”

As act II continues, Nina is still infatuated with Trigorin and his celebrity as a writer. When Trigorin sees the dead gull at Nina’s feet, he says, “…an idea that occurred to me. An idea for a short story. A young girl grows up on the shores of a lake, as you have. She loves the lake as the gulls do, and is as happy and free as they. But a man sees her who chances to come that way, and he destroys her out of idleness, as this gull here has been destroyed.”

At the end of the play, Treplieff does kill himself. If you can believe it, Chekov wrote the play as a comedy.

Chekov’s plays and stories leave room for endless symbolism and allegory in his characters, the dialogue and the landscapes. And reading The Seagull, it’s hard to avoid the allegory and parallels with the paths of Putin, Russia and the Ukraine.

Tossing aside all the fancy geopolitics, Putin resembles the spurned lover stuck in the past, convinced that Ukraine should still be part of his gauzy vision of an intact Soviet Union. In this Russian version of unrequited love, rather than getting on with his life—the life of an oligarch with billions of dollars, shirtless days riding horseback in Siberian summers, and staged hockey games—Putin just can’t let go. He stalks Ukraine, first with forays into the Crimea, then with forays into its eastern provinces, and finally breaking down the door with tens of thousands of soldiers trying to vanquish Kiev.

Like Treplieff, for years Putin has been frustrated for what he considers the disrespect shown Russia by the west, likely personalized to be interpreted as disrespect for himself. Like Treplieff, he attempts to kill the gull when he can’t get the gal. We don’t know what will happen in Putin’s third act. But we can be certain it will be dark. And very Russian.