by Emrys Westacott

What should we do with our leisure? In his Politics, Aristotle identifies this as a fundamental philosophical question. Leisure, here, means freedom from necessary labor. If we have to spend much of our time working, or recuperating in order to work more, the question hardly arises. But if we are free from the yoke of necessity, how we answer the question will say much about our conception of the good life for a human being.

It is to be hoped that the question will one day become the primary question confronting humanity. This hope rests on the prospect of a world in which technological progress has advanced to such a degree that no one needs to work more than a few hours per week in order to enjoy a reasonably comfortable and secure existence. Before the industrial revolution such an idea was a mere fantasy; but given the rate of technological progress over the past two hundred years–and particularly in light of the recent digital revolution and the advent of what has been called “the second machine age”–the prospect of a much more leisurely life for those who want it is at least conceivable.

The fifteen-hour work week envisaged by John Maynard Keynes in “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930) is hardly just around the corner, though. One problem, of course, is that there are some kinds of work that are not easily automated. Consider home care for the disabled, sick, and elderly. Machines are capable of cognitive tasks far beyond the ability of humans, yet many of the basic manual tasks caregivers perform are still very difficult for robots to replicate. Beyond that, though, caregivers also provide human contact and companionship. For machines to offer an adequate substitute for this takes us well into the realm of science fiction (which is not say into the realm of impossibility).

The deeper problem, though, is political rather than technological. Read more »

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks. It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter.

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter. I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.  Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

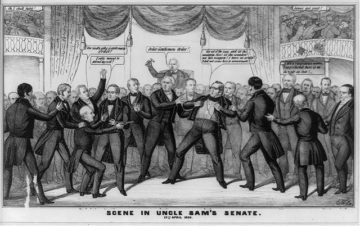

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience. At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

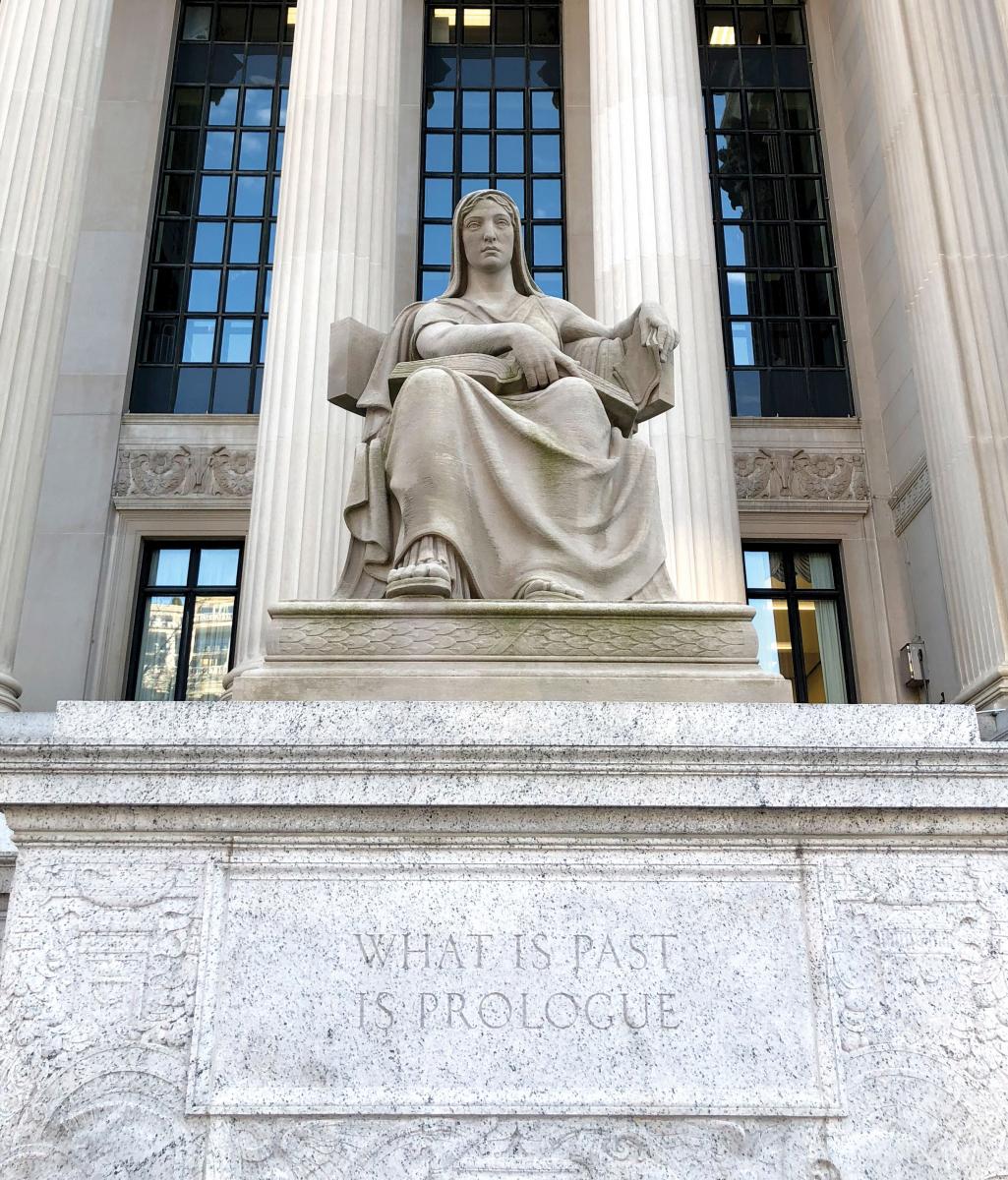

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian.

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian. He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.