by Derek Neal

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

Indeed, the American in Europe is an empty vessel. Like the negative of an image, his surroundings are filled in, and the empty space where a person should be appears in outline. Thus, the American has the task of creating his own identity, of forging his own personality without the aid of history or culture but through sheer willpower alone. Whether this is a true representation of what it means to be American is irrelevant; this is the conception that writers have created in literature, giving rise to the myth of the American in Europe. Every time an American character enters Europe, they enter into this legacy, intentionally or not. It is a sort of self-orientalizing, as one can stereotype and mythologize oneself just as one can others.

Henry James and James Baldwin are two progenitors of this genre. For both, the American is a prodigal character and the return to Europe is a return home, to where his real roots lie. The trip to Europe, or the permanent move in some cases, is a search for self-knowledge, and similarly to the biblical Garden of Eden, Europe is often cast as a place of sin and danger, a place one might never escape from if one isn’t careful.

In his 1954 essay “A Question of Identity,” Baldwin writes that, “The American in Europe is everywhere confronted with the question of his identity” and that “this prodigious question…seems, germ like, to be vivified in the European air…It confronts everyone”. This is the question Christopher Newman discovers in James’ The American, the question Lambert Strether explores in The Ambassadors, and the question David must respond to in Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. It is certainly the question that James and Baldwin asked themselves as well while living in Europe.

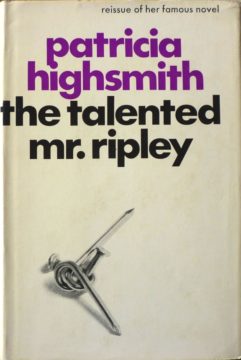

It is also a question Patricia Highsmith takes up in The Talented Mr. Ripley, a novel I picked up recently and am in the process of reading. The Talented Mr. Ripley, being a work of genre fiction rather than what might classically be termed “literature,” is able to more clearly and explicitly explore the question of American identity because it isn’t overly concerned with being real or believable. Tom Ripley, the titular character, is an enigma. Like the Americans that Baldwin writes about as “having attempted, on more or less personal levels, to lose or disguise their antecedents,” Ripley, too, has no past: he was orphaned as a child and ran away from his Aunt’s house as a teenager. He lives a life of petty crime and scams in New York City, the easiest place to be anonymous in America, before being presented with an opportunity to go to Europe.

He is sent to Europe, much like Lambert Strether in The Ambassadors, in order to persuade an acquaintance of his to return home and enter the family business. In fact, Highsmith makes the connection between the two novels explicit by having Dickie Greenleaf’s father (Dickie being the man lost in Europe) ask Tom if he’s read The Ambassadors. Tom hasn’t, but he tries to borrow it from the ship library as he sails to Europe, only to be told that he’s not allowed as the library is for passengers of a different class. Tom’s inability to read The Ambassadors is a joke on the part of Highsmith. In James’ novel, Lambert Strether initially attempts to convince his future son-in-law to return home as he fears, along with the rest of the family, that his son-in-law Chad had been corrupted by a European way of life. However, the more time Strether spends in Paris, the more he comes to appreciate the European way of life and the more critical he becomes of American puritanism. The self-knowledge Strether gains seems as if it will be lost on Ripley, however, represented by his inability to find the book and understand his mission in a new light.

Writing once again about the prototypical American, Baldwin writes that “hidden in the heart of the confusion he encounters here is that which he came so blindly seeking: the terms on which he is related to his country, and to the world.” Strether discovers this, Ripley, it appears, will not. To answer this question, according to Baldwin, one must recognize and acknowledge “the very nearly unconscious assumption that it is possible to consider the person apart from all the forces which have produced him.” For Baldwin and James, people are products of history and culture, and the mistake Americans make is thinking that nothing is lost when one tries to forcefully sever oneself from one’s roots. This is, of course, the history of America itself, both intentionally in terms of immigration and wars for independence, and involuntarily in terms of slavery. Understood in this way, Tom Ripley is perhaps the quintessential representation of an American in literature.

Ripley is not only a man without a past; he’s a man without a personality. Early in the novel, Ripley lists all the different things he can do, the most ominous of which is “impersonate practically anybody.” Tom is not interested in knowing himself or his past, but is like the American students about whom Baldwin writes: “They thus lose what it was they so bravely set out to find, their own personalities, which having been deprived of all nourishment, soon cease, in effect to exist.” Highsmith makes this idea explicit when Ripley murders the man he was meant to bring home and then assumes his identity, changing his appearance to match that of his victim and adopting his mannerisms, patterns of speech, and belongings. Ripley becomes Dickie Greenleaf and achieves “the clean state he had thought about on the boat coming over from America.” Highsmith writes that “this was the real annihilation of his past and of himself, Tom Ripley, who was made up of this past, and his rebirth as a completely new person.”

Paradoxically, Ripley reenacts his ancestors move to America in reverse, moving to Europe in order to eliminate his past and become a new person. Baldwin writes at the end of his essay that “from the vantage point of Europe he [the American] discovers his own country…bring[ing] to an end the alienation of the American from himself.” For Ripley, this moment may never come.