by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

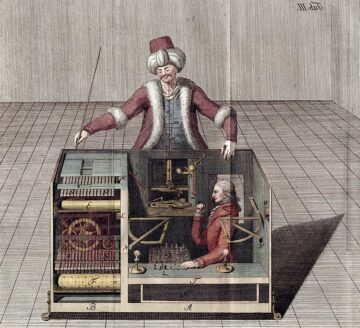

Artificial intelligence is generally conceptualized as a new technology which goes back only decades. In the popular imagination, at best we stretch it back to the Dartmouth Conference in 1956 or perhaps the birth of the Artificial Neurons a decade prior. Yet the impulse to imagine, build, and even worry over artificial minds has a long history. Long before they could build one, civilizations across the world built automata, thought about machines that could mimicked intelligence, and thought about the philosophical consequences of artificial thought. One can even think of AI as an old technology. That does not mean that we deny its current novelty but rather we recognize its deep roots in global history. One of the earliest speculations on machines that act like people. In Homer’s Iliad, the god Hephaestus fashions golden attendants who walk, speak, and assist him at his forge. Heron of Alexandria, working in the first century CE, designed elaborate automata that were far ahead of their time: self-moving theaters, coin-operated dispensers, and hydraulic birds.

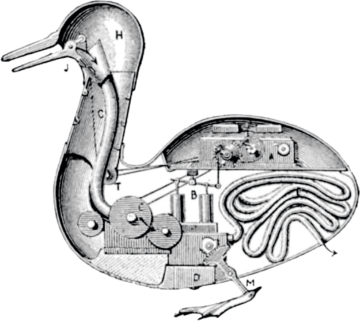

Aristotle even speculated that if tools could work by themselves, masters would have no need of slaves. In the medieval Islamic world, the Musa brothers’ Book of Ingenious Devices (9th century) described the first programmable machines. Two centuries later, al-Jazari built water clocks, mechanical musicians, and even a programmed automaton boat, where pegs on a rotating drum controlled the rhythm of drummers and flautists. In ancient China we observe one of the oldest legends of mechanical beings, the Liezi (3rd century BCE) recounts how the artificer Yan Shi presented a King with a humanoid automaton capable of singing and moving. Later, in the 11th century, Su Song built an enormous astronomical clock tower with mechanical figurines that chimed the hours. In Japan, karakuri ningyo, intricate mechanical dolls of the 17th–19th centuries, were able to perform tea-serving, archery, and stage dramas. In short, the phenomenon of precursors of AI are observed globally. Read more »