by Kyle Munkittrick

Two types of people are very worried about global fertility — social conservatives and Silicon Valley weirdos. I have the rare privilege of having been both at one point in my life, neither at the same time, and, how apropos, I also have training in bioethics. This is my moment.

Pro-natalists want more babies. They argue that total fertility rates being below replacement level is really bad. They’re very probably right. Unfortunately, the conservatives and weirdos not only almost perfectly oppose and cancel out each other, but are also tying their own rhetorical shoelaces together.

The problem of low fertility is a combination of social and technological barriers. Social conservatives tend to want social solutions and oppose technological ones. The Silicon Valley weirdos tend to want the technological solutions and oppose the social options. Combined, both groups end up failing to convince each other and skeptical normies. Who needs anti-natalists when you’ve got pro-natalists like these?

As a result most normal people think the solution fertility problem is obvious. They are wrong. If you think it’s obvious, read Dr. Alice Evan’s interview with Ross Douthat, her blog on Substack, or these threads by @StatisticUrban. If it’s not obvious, what are the probable causes? Read more »

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

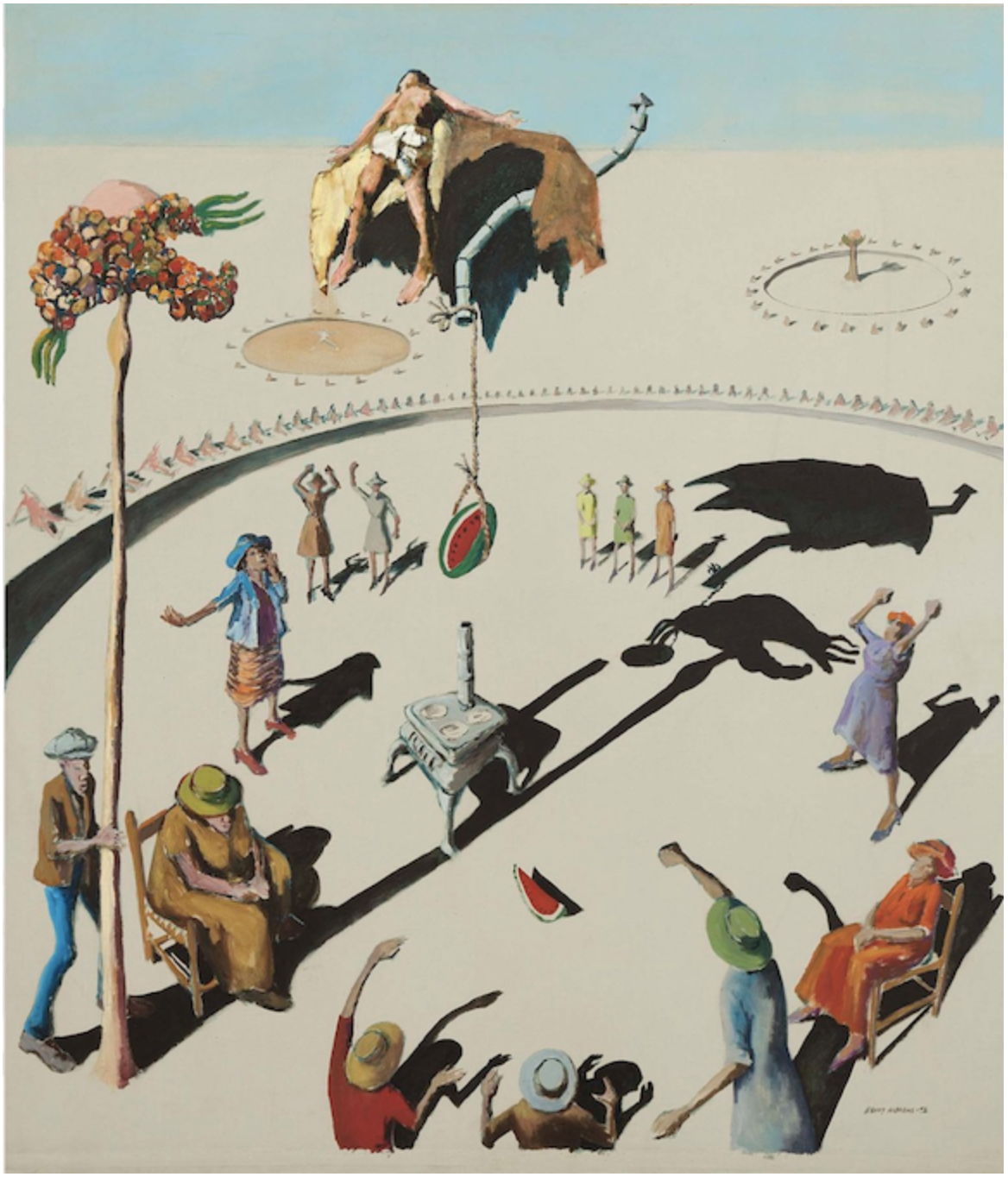

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing. Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

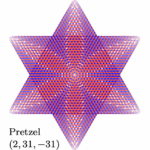

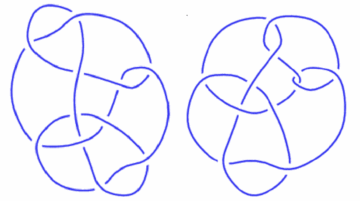

Mathematics is

Mathematics is

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.