by Marie Snyder

I’m running for an elected position: school board trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this:

trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this:

I’ve been cautioned not to tweet so much about covid because it could cost me votes. But we’re sleepwalking through a crisis that could be averted if we can just open our eyes to it. Hospitalizations and deaths are way higher now than this time in the previous two years.

Protecting kids by possibly saying that one thing that finally lights a fire under chairs to #BringBackMasks is far more important to me than winning a popular vote. Look at young people dropping dead from strokes! The pandemic didn’t end. We’re not easing out of it. We’re in the thick of it. But it appears that some people in power want you at work and going to restaurants and bars and travelling more than they care to prevent children getting sick and hospitals overflowing.

There are variants that bypass vaccines. A well-fitting N95 can stop all variants. And CR boxes filter all variants. If we #BringBackMasks then more of us stand a fighting chance at avoiding getting this repeatedly, accumulating risk factors for brain damage or strokes. Masks don’t stop us from living; Covid does.

I closed my laptop to avoid reading the expected onslaught from haters, but, once I mustered the courage to look, found incredible support instead. Hundreds of new people followed me, and my email was suddenly full of donations and requests for signs. That one tweet appeared to do more than weeks of walking door to door. Read more »

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

Before leaving Santa Fe I spent (yet another) morning at a coffeehouse. It’s an urban sort of behavior, and a Bachian one too – you might know about Zimmerman’s in Leipzig, the coffeehouse where Bach brought ensembles large and small to perform once a week. It seems to have been a chance to make some non-liturgical music, a relief from Bach’s otherwise very churchy employment.

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere.

At a recent tournament sponsored by the St. Louis Chess Club, 19-year old Hans Niemann rocked the chess world by defeating grandmaster Magnus Carlson, the world’s top player. Their match was not an anticipated showdown between a senior titan and a recognized rising phenom. The upset came out of nowhere. They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

They all want it: the ‘digital economy’ runs on it, extracting it, buying and selling our attention. We are solicited to click and scroll in order to satisfy fleeting interests, anticipations of brief pleasures, information to retain or forget. Information: streams of data, images, chat: not knowledge, which is something shaped to a human purpose. They gather it, we lose it, dispersed across platforms and screens through the day and far into the night. The nervous system, bombarded by stimuli, begins to experience the stressful day and night as one long flickering all-consuming series of virtual non events.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.

If you look at my profiles online, they are catered to appear normal, if dated. I haven’t posted very much over the past few years, and those that I have posted have been relatively mundane, which mark the relatively mundane moments of my life. They’re honest and small, like a photo of the street as I walk to school, or a picture of my friends at a park. My profile molds itself to match me.

If you look at my profiles online, they are catered to appear normal, if dated. I haven’t posted very much over the past few years, and those that I have posted have been relatively mundane, which mark the relatively mundane moments of my life. They’re honest and small, like a photo of the street as I walk to school, or a picture of my friends at a park. My profile molds itself to match me. Before I met Hayat Nur Artiran, I had only had a raw understanding of what female selfhood may look like, a notion I have been attempting to refine in my writings over many years. Here, at the Mevlevi Sufi lodge in Istanbul, I received a lifetime’s worth of illumination about the power of the spirit in the company of Nur Hanim, beloved Sufi Hodja and the President of the Sefik Can International Mevlana Education and Culture Foundation. A researcher, author and spiritual leader on the Sufi path known as the Mevlevi order (based on the teachings of Maulana Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi, known in the West simply as the poet Rumi), Nur Hanim’s accomplishments shine a light on an ethos that has transformed hearts for nearly a millennium. More instrumental than personal achievement in this case, is the Sufi substance and finesse that Nur Hanim has nurtured in the running of this Mevlevi lodge. Spending a day here, on my most recent visit to Istanbul, I came to experience what I had thought possible, based on my Muslim faith, but had never witnessed before: men and women coexisting, learning, working and serving in harmony, a place where one forgets the ceaseless tensions between genders, generations, ethnicity, or those caused by differences in religious beliefs or the self-worshipping individualism that has become the insignia of modernity.

Before I met Hayat Nur Artiran, I had only had a raw understanding of what female selfhood may look like, a notion I have been attempting to refine in my writings over many years. Here, at the Mevlevi Sufi lodge in Istanbul, I received a lifetime’s worth of illumination about the power of the spirit in the company of Nur Hanim, beloved Sufi Hodja and the President of the Sefik Can International Mevlana Education and Culture Foundation. A researcher, author and spiritual leader on the Sufi path known as the Mevlevi order (based on the teachings of Maulana Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi, known in the West simply as the poet Rumi), Nur Hanim’s accomplishments shine a light on an ethos that has transformed hearts for nearly a millennium. More instrumental than personal achievement in this case, is the Sufi substance and finesse that Nur Hanim has nurtured in the running of this Mevlevi lodge. Spending a day here, on my most recent visit to Istanbul, I came to experience what I had thought possible, based on my Muslim faith, but had never witnessed before: men and women coexisting, learning, working and serving in harmony, a place where one forgets the ceaseless tensions between genders, generations, ethnicity, or those caused by differences in religious beliefs or the self-worshipping individualism that has become the insignia of modernity.  May of 1851, London, the world’s first World’s Fair.

May of 1851, London, the world’s first World’s Fair. What all went inside? Apart from the full-grown trees and gallant blocks of statuary, a quick glance at a single page of the Exhibition’s

What all went inside? Apart from the full-grown trees and gallant blocks of statuary, a quick glance at a single page of the Exhibition’s  Another cultural benefit of my travels, particularly in early days, used to be my exploration of international cinema. I have already mentioned how going out of India I became exposed to a riot of European art films. In later years I also saw some superb art films from Argentina, Brazil, Japan, Iran, South Korea, and Taiwan. In the US in many cities some of these art films were not always easily available, and I sometimes saw them in visits to New York or London, though with some lapse of time Pacific Film Archive in the Berkeley campus showed some good international films. Every time I went to Kolkata my friend Samik Banerjee told me about the new Bengali art films that came out in the months I was away and sometimes took me to their special screenings. Through him I came to know some of the major film directors and actors in Kolkata. Meanwhile the quality of American films improved a great deal. But the general commercial film world in the US largely catered to adolescent fantasy worlds or antics of superheroes from comic books or dystopian science fiction, none of which held much attraction for me. Even in more grown-up American films one often missed the sharp, witty, historically informed, and politically engaged conversation of friends and also a kind of cerebral sexuality that I used to associate with French films, for example– a character in Godard’s film Contempt famously said in bed: “I love you totally, tenderly, tragically”.

Another cultural benefit of my travels, particularly in early days, used to be my exploration of international cinema. I have already mentioned how going out of India I became exposed to a riot of European art films. In later years I also saw some superb art films from Argentina, Brazil, Japan, Iran, South Korea, and Taiwan. In the US in many cities some of these art films were not always easily available, and I sometimes saw them in visits to New York or London, though with some lapse of time Pacific Film Archive in the Berkeley campus showed some good international films. Every time I went to Kolkata my friend Samik Banerjee told me about the new Bengali art films that came out in the months I was away and sometimes took me to their special screenings. Through him I came to know some of the major film directors and actors in Kolkata. Meanwhile the quality of American films improved a great deal. But the general commercial film world in the US largely catered to adolescent fantasy worlds or antics of superheroes from comic books or dystopian science fiction, none of which held much attraction for me. Even in more grown-up American films one often missed the sharp, witty, historically informed, and politically engaged conversation of friends and also a kind of cerebral sexuality that I used to associate with French films, for example– a character in Godard’s film Contempt famously said in bed: “I love you totally, tenderly, tragically”.

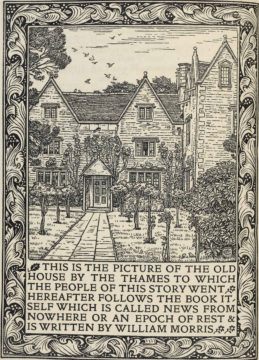

What does the word “utopia” mean to the battle-scarred denizens of the twenty-first century? A shockingly unscientific survey of the nine or ten people I buttonholed last week suggests that the key connotations of the word are: ideal, perfect, imaginary, unrealistic, and unattainable. I’ve arranged these terms purposefully in that order, so that they imply not a static and fixed definition but rather a narrative arc, a falling away from hope into disappointment: all of the people I spoke to (students and colleagues at the large Southern state-flagship university where I teach, so a fair cross-section of ages, races, ethnicities, and genders) firmly believed that the word “utopia” denotes an unrealistic or quixotic goal. It’s not my thesis here that disappointment is the necessary fate of any utopian project, but it might be a provisional thesis that most people living in Western cultures today think that it is.

What does the word “utopia” mean to the battle-scarred denizens of the twenty-first century? A shockingly unscientific survey of the nine or ten people I buttonholed last week suggests that the key connotations of the word are: ideal, perfect, imaginary, unrealistic, and unattainable. I’ve arranged these terms purposefully in that order, so that they imply not a static and fixed definition but rather a narrative arc, a falling away from hope into disappointment: all of the people I spoke to (students and colleagues at the large Southern state-flagship university where I teach, so a fair cross-section of ages, races, ethnicities, and genders) firmly believed that the word “utopia” denotes an unrealistic or quixotic goal. It’s not my thesis here that disappointment is the necessary fate of any utopian project, but it might be a provisional thesis that most people living in Western cultures today think that it is. which it affects everyday German speech will only become apparent in hindsight, after its traces are already securely imbedded in the language. In Europe, the immigrant presence rarely finds acknowledgement in high culture, but you can see it wielding its influence on popular culture in subversive ways. The Turkish ghetto identity, which developed in response to the discrimination a younger, German-born generation of second- and third-generation migrant worker families continues to face there, particularly in the wake of German Reunification and the deadly xenophobic attacks that followed, has always identified heavily with Black American subculture. The Turkish-German assimilation of Hip Hop and Rap was seamless: it gave them a language, dealt embarrassing blows to German political correctness and its many blind spots, incorporated taboo themes otherwise held to be racist, sexist, or anti-Semitic, and posed questions that cultural commentators, at a complete loss, are still largely trying to evade.

which it affects everyday German speech will only become apparent in hindsight, after its traces are already securely imbedded in the language. In Europe, the immigrant presence rarely finds acknowledgement in high culture, but you can see it wielding its influence on popular culture in subversive ways. The Turkish ghetto identity, which developed in response to the discrimination a younger, German-born generation of second- and third-generation migrant worker families continues to face there, particularly in the wake of German Reunification and the deadly xenophobic attacks that followed, has always identified heavily with Black American subculture. The Turkish-German assimilation of Hip Hop and Rap was seamless: it gave them a language, dealt embarrassing blows to German political correctness and its many blind spots, incorporated taboo themes otherwise held to be racist, sexist, or anti-Semitic, and posed questions that cultural commentators, at a complete loss, are still largely trying to evade.