by Michael Abraham

It was in the midst of thinking about my own childhood and friendships, of thinking about faith and magic and the End of the World and the World to Come, in the midst of reflecting quite deeply on these things, which for me are so profoundly interwoven, so profoundly interwoven because, in the tapestry they make together, there is, glimmering, the idea of what love is and means, the sense I have of amory, of life’s affectionate trajectory and the purpose of affection in the trajectory of life—it was in the midst of reflecting on these these things and of writing about them over and over that I met a man we’ll call Khalid.

I was in Tribeca, playing pool with the friend I once liked to call Shakti in my writing. She had to run off to a dinner, and so I was left on my own with a beautiful summer night thrumming around me. O, it was perfect. It was deep purple and eighty degrees with a strange chill in the breeze—everything New York in August is supposed to be. I was two blocks from the train to my house, but how could I go home on such a night? So, I decided I would walk north from Tribeca to the Christopher Street pier. This pier is a mightily historical place, both for me personally and for queer history itself. It was on this and the surrounding piers that voguing was invented by unhoused Black and Brown queer youth in between turning tricks, as they dance battled to pass the night. It was on this and the surrounding piers that so much of the twentieth century gay and trans lifeworld of sex and friendship existed. It was also on this pier that I first discovered myself as a queer man. I had been gay long before the discovery of course; I came out at fourteen. But I was not queer until I was nineteen. I was taking a class my second semester of freshman year at NYU, taught by Tamuira Reid, in the writing of creative nonfiction and immersive journalism. For our final projects, we had to pick something to immersively research, something to involve ourselves in, and then write a long-form lyrical essay about it. Having recently been exposed to Elegance Bratton’s then-unreleased film, Pier Kids, which follows the lives of three unhoused queer youth as they secure housing, I decided what I would write about were just these people, the unhoused youth of color who make the Christopher Street pier their nightly home. Looking back, I can see how voyeuristic and naïve this was. But I didn’t want to meet the pier kids to gawk at them. I had a sense, a sense merely, that they knew something, many things, about the kind of people we are, them and me, that I did not yet know. Read more »

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

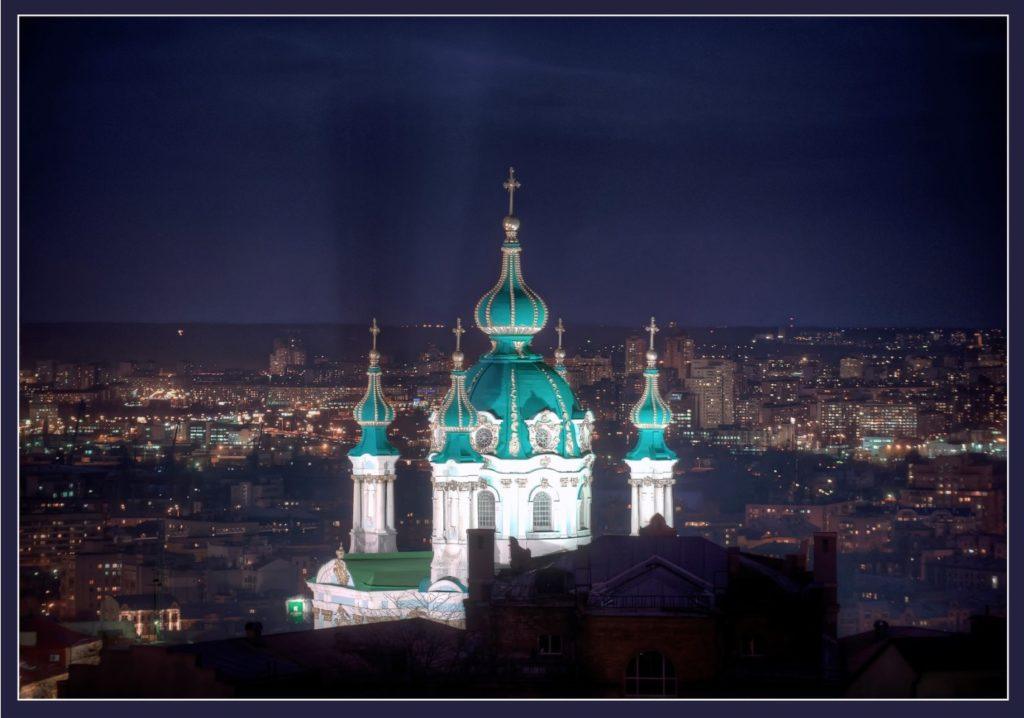

Naomi Lawrence. Tierra Frágil, 2022.

Naomi Lawrence. Tierra Frágil, 2022. Come die with me.

Come die with me. by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this:

trustee. It’s a relatively minor position and non-partisan, so there’s no budget or staff. There’s also no speeches or debates, just lawn signs and fliers. Campaigning is like an expensive two-month long job interview that requires a daily walking and stairs regimen that goes on for hours. Recently, some well-meaning friends who are trying to help me win (by heeding the noise of the loudest voices) cautioned me to limit any writing or posting about Covid. It turns people off and will cost me votes. I agreed, but then had second thoughts the following day, and tweeted this: