by Michael Liss

Simply because people disagree with an opinion is not a basis for questioning the legitimacy of the court. —Chief Justice John Roberts

Ah, if only it were that simple. It’s not, so fasten your seatbelt because the men and women in black are back.

First, the good news. The Court welcomed its newest member in Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, and the rookie can play. She acquitted herself quite well in her first oral argument in Merrill v. Milligan. Justice Jackson joins Justices Kagan and Sotomayor in the “Lost Battalion” of Liberals, but there is every reason to think she can make her mark.

Now to the bad: Regrettably, it must be noted that SCOTUS is back in session, and no good can come from this. Having wreaked havoc across a broad spectrum last term, Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett are expected to continue to gorge themselves. To paraphrase Sir Edward Grey on the eve of World War I, “The lamps are going out on our rights. We shall not see them again.”

Before they further immerse us in gloom, let’s acknowledge that Chief Justice Roberts is suffering as well. He’s the guy who must clean up the mess left by the Dobbs leak, and then the bigger one caused by the Dobbs decision. He’s also the caretaker of the Court’s reputation, built over more than 230 years, as a temperamentally conservative place, moving slowly and thoughtfully, not doing too much at the same time, not getting too far ahead of itself or the public. Suitable for a John Roberts.

Of course, it’s not really the Roberts Court anymore, not when the Chief was serially ignored by the conservative super-majority every time he asked for restraint. It’s lonely at the (ceremonial) top, especially when you don’t have an ideological home anymore. Still, the job demands it, demands that he, more than anyone else, make the case for institutional continuity and legitimacy.

Roberts wouldn’t have spoken out if he hadn’t perceived a real issue. He knows his conservative brethren (and sister) went too fast and too far last term. He also knows that he is working in a new era unlike anything we’ve seen before in our lifetimes: Trust in government is disappearing; anger towards the “elites” is increasing. An astonishing number of people in this country no longer buy the system the Founders bequeathed to us. It doesn’t help that they are constantly bombarded by appeals from faux-populist politicians and the media that serves them, but there is an irreducible kernel of truth. The “haves” have looked to their own interests first. Those with power have often used that power for their own purposes, and not for the common good.

Roberts’ Court is part of that. As much as the Chief may fight the idea, as much as he may insist that the Court’s legitimacy should not be questioned, he must acknowledge that SCOTUS has thrust itself into the middle of far more controversies than necessary. And it’s picked a side, pursuing Republican policy and electoral goals with an ardor unmatched since Napoleon courted Josephine.

The public really doesn’t understand the inside baseball of the Shadow Docket, or what granting cert means, or how convenient and even disingenuous the conservative wing’s fun-house-mirror legal logic and history recitals are. But they can certainly identify the winners and losers, and MAGA-Red is the color of the day.

When you flip a coin 50 times and it always comes up heads, you begin to get the idea that the “legal” game is, well, rigged. Maybe the results thrill you, maybe they infuriate you, but the message is consistent, and for Roberts, vexing: in any case that involves either politics or controversial public policy, the Supreme Court is no longer a forum where litigants can all expect a fair hearing. The Court may have the trappings of dignity, the solemnity of procedure, the majesty of the atmospherics, but the result is preordained, like a Senate confirmation hearing. Almost invariably, you vote the party line.

There is just no way that, when Justices act like politicians, they can avoid the perception that they are politicians, with the public viewing them accordingly. They simply cannot expect to be seen as anything more, and their status must be downgraded proportionate to the partisanship they show.

Does legitimacy matter? I’ve seen a lot of talking heads and editorials that insist it does. Legitimacy is a predicate to voluntary compliance. The public will refuse to heed a decision that overreaches or is a product of bias or partisanship. The Court itself lacks the temporal power to enforce those decisions. Many have referenced Justice John Marshall’s 1832 ruling in Worcester v. Georgia regarding the recognition of Cherokee sovereignty within their territories. Upon hearing it, Andrew Jackson (reputedly) rasped out, “Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

In the real world, in the practical world, Jackson was right. Marshall had words; Jackson (and like-minded State and Territorial Governors) had the whip. Nothing so ethereal as a Supreme Court ruling was going to stop folks who wanted power over Indian lands and weren’t too squeamish about how they took it. Especially when the “take-ees” were people whom they feared and despised.

The example is compelling, but I think it’s misapplied. In politics, Machiavelli is often right: it is better to be feared than loved, if one cannot be both. Being loved, being Legitimate, didn’t solve Marshall’s problem in 1832. Jackson was feared and could be lawless without consequence.

Still, what does legitimacy really mean, or, more specifically, what do Supreme Court Justices think it means? Given that the midpoint of this argument begins with the conservative-but-institutionalist Roberts, it’s useful to start there.

Justice Roberts seems to be a true believer. His ideal is a distinctly conservative Court adopting a gradualist approach towards that conservatism. He doesn’t want to break all the china in the cabinet at the same time. He wants the reputation of the Court to be perceived as thoughtful and non-partisan if not non-ideological. Roberts recognizes that it’s not just the title and the robes that make for legitimacy, it must be joined with “good works.”

I don’t need to replay the Garland/Gorsuch/Kavanaugh/Barrett spectacle, but I doubt Roberts was happy with the optics of it. Yet, if the Trump Trio had enhanced the Court’s rightward tilt but done it with a little more care as to appearances—if they could even pretend to be above politics on most issues—the Court could retain the patina of impartiality that Roberts craved.

Of course, it didn’t happen. Justices Thomas and Alito had waited far too long to wield the wrecking ball, and they probably heard Roberts’ advice as Sunday-school-ish and acted accordingly. Now, he is dreading what’s next: adjudicating disputes arising from the upcoming Midterms and, likely, the 2024 Presidential election in an environment where, as things have evolved since 2020, nearly everyone expects SCOTUS to act as the GOP’s most important wingman.

Let’s look left for a moment at Justice Kagan’s perspective. In September, in remarks given at Northwestern University School of Law, she said “When courts become extensions of the political process, when people see them as extensions of the political process, when people see them as trying just to impose personal preferences on a society irrespective of the law, that’s when there’s a problem—and that’s when there ought to be a problem.” This is one of several criticisms she’s levied since the Court has taken its rightward lurch, but is she correct?

Partially. Kagan is infuriated that the conservative bloc ripped through virtues we were all taught in law school—judicial restraint, respect for precedent, and precision when citing previous cases and legislative history. In this, she’s probably quite close to Roberts, even though the two disagree on basic philosophy. But there’s no question her process arguments are made more fervent because of the results. It’s not fun to lose, repeatedly. She’s right about process, right about legitimacy, and certainly reflective of liberal and centrist views on the subject, but her motives are being questioned by conservatives.

Now to a third player on the legitimacy argument, Justice Alito. In response to questions from The Wall Street Journal, he weighed in: “It goes without saying that everyone is free to express disagreement with our decisions and to criticize our reasoning as they see fit. But saying or implying that the court is becoming an illegitimate institution or questioning our integrity crosses an important line.”

More than a little arrogant. Alito’s problem is that he carves out for himself and his ideological soulmates a space that is not permitted anyone in the public eye: to be free from the questioning of one’s motives. Justice Alito wants to be obeyed. He assumes that, with the job and the robe, he, and the decisions he either joins or authors himself, must be treated with complete deference. His attitude is the embodiment of the “Because I Said So Doctrine.”

He can do that because of the fusion of the conservative wing with the Republican Party. More than legitimacy, that relationship creates power, and quite a lot of it. This Term will be all about the Because I Said So Doctrine. Expect more overreaching holdings to impose a new conservative ideology on the country. Already teed up are new cases on the Voting Rights Act, The Clean Water Act, affirmative action in college admissions, access to social media platforms, and the awful, existential threat to our right to choose our leaders that is the Independent State Legislature theory.

None of this will come with Roberts’ “good works,” and none will be perceived as “legitimate.” Does it matter? Here’s where I would differ from most of the others who have made excellent cases that legitimacy is important. They argue it’s important because, absent perceived legitimacy, there’s a risk the Court’s rulings won’t stand. The problem is that the Court’s rulings will stand, enforced as a matter of law. It is true that SCOTUS, and individual Justices, can never claim legitimacy merely from the job. But the dangerous part is that they don’t have to, if they have partners in politics. Every bit of new ground broken by the conservatives on SCOTUS creates new opportunities for motivated people down the chain, particularly at the enforcement level. Each new conservative initiative gives SCOTUS greater reach. It all becomes a self-reinforcing system.

When SCOTUS picks a side, when, through its rulings, it invites even more radical overreach from states led by people who share its political philosophy and lower federal courts led by judges looking to climb onto someone’s future shortlist, when it acts to enhance a party’s electoral goals, then it gives up any claim to the moral high ground. But it does have power, and for now, power seems to be more than enough.

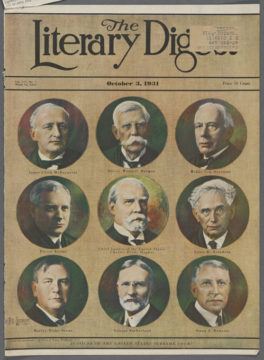

The image above is from 1931, and includes eight of the “Nine Old Men” on SCOTUS when it blocked key portions of FDR’s New Deal programs. Oliver Wendell Holmes retired in January of 1932 and was replaced by Benjamin Cardozo. Thanks to the NYPL Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6eefe460-dda8-0130-9163-58d385a7b928