by Michael Liss

Never before in world history has a nation been so endowed with wealth and power, yet so plagued with doubt as to the proper use of that wealth and power.

Grim, right? Would you feel better or worse if I told you that came from written testimony given to Congress by Walter Reuther, then head of the United Autoworkers Union, in…1969.

It’s amazing how often “plagued with doubt” can be applied to something related to economics. Reuther was way ahead of his time. Not only did he advocate for workers’ rights, including the then-radical idea of profit-sharing, but also healthcare, civil rights, women’s rights, conservation, and education. He helped make Labor a player on key issues of his time, while surviving a couple of assassination attempts.

I mention Reuther because, a half-century after his death, those issues remain as pertinent, and as unresolved, as they did in 1969. They were also among the topics touched upon at the Center on Capitalism and Society’s 19th Annual Conference, titled “Present Failings and Ways Forward: Private Sector, Public Sector.”

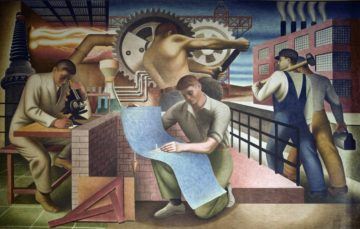

The Center was formed in 2002 to study Capitalism’s strengths and weaknesses and to grapple with big issues facing it in a modern world. Founder (and 2006 Nobel Prize winner) Edmund Phelps has long envisioned and advocated for what he calls the “Good Economy,” which produces jobs that give meaning, confer personal dignity, and provide enough so that “Mass Flourishing” is possible. Productivity growth, innovation, and dynamism are all essential to that. The “Present Failings” part of the title of this year’s conference is reflective of the reality around us—an American economy showing a flabbiness, a loss of velocity, a failure to provide opportunity. In his remarks at the conference, Phelps himself acknowledged how far we have drifted from that goal.

The question is, why? What are we doing, or failing to do? Read more »

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.

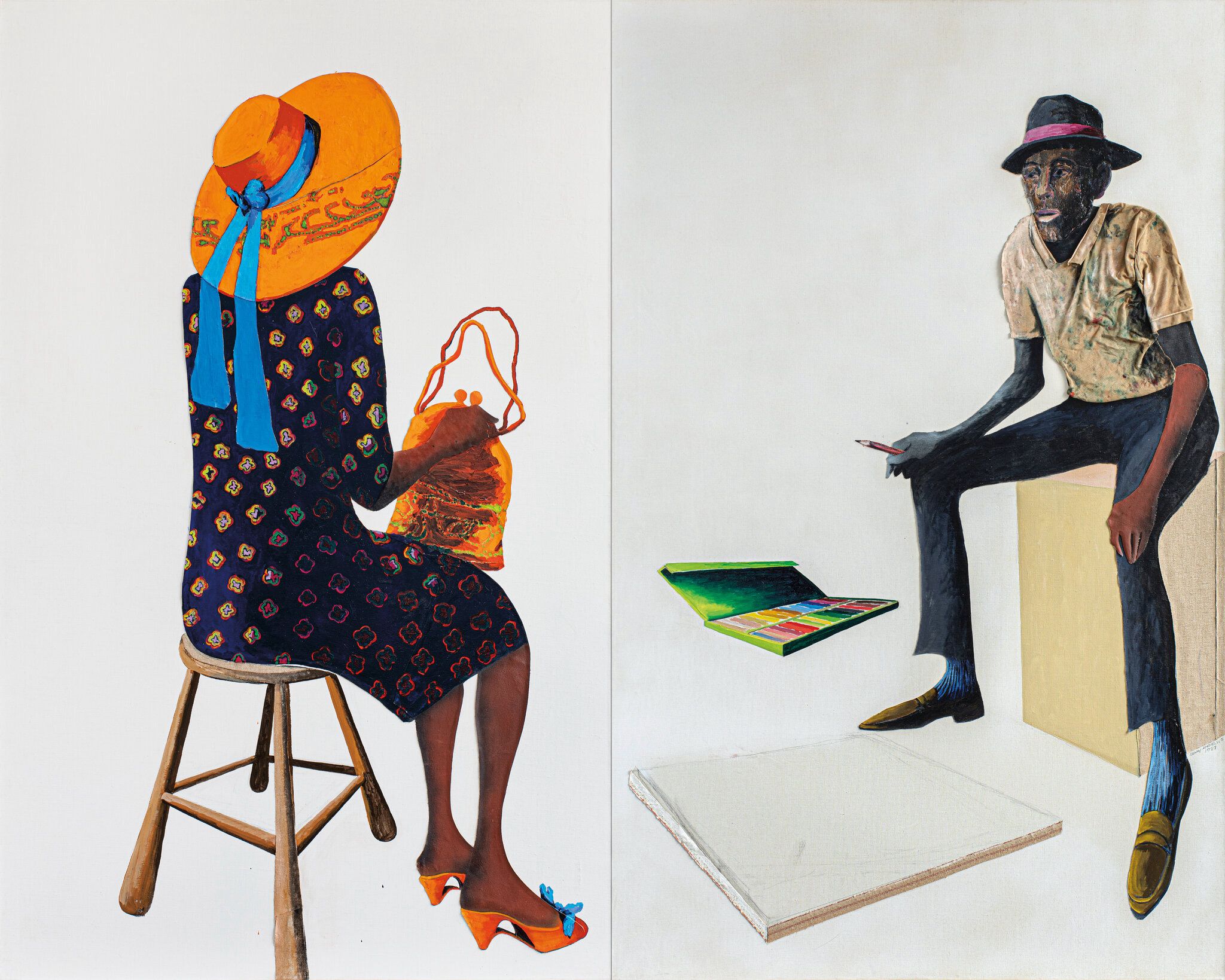

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous. Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Now there is a

Now there is a

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”