by Marie Snyder

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.Some recent climate change articles are painting a bleak picture. At the Paris Agreement in 2015, countries around the world signed on to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) in order to cap warming at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2030. It’s become clear that we won’t be able to make it.

Current pledges for action by 2030, if delivered in full, would mean a rise in global heating of about 2.5°C and catastrophic extreme weather around the world. . . . Global emissions must fall by almost 50% by that date to keep the 1.5°C target alive. . . . We had our chance to make incremental changes, but that time is over.

The climate crisis has been a test of our ability to put long term collective needs over individual desires, and we failed miserably. It’s no wonder we’re not sufficiently mitigating SARS-CoV-2. Despite all our knowledge and technology and ability, we just don’t want to be inconvenienced. This attitude dates at least as far back as Plato’s Protagoras, as Socrates argues that “our salvation would lie in the art of measurement,” specifically the ability to measure long term benefits against short term when measuring pleasures and pains. It appears that no amount of ingenuity can foist us out of our short-sightedness. We’re horrible at measuring current pleasures against distant pains, but even if we could, we also enjoy doing wrong too much for knowledge alone to lead us down the right path. Thousands of years after it was explained in writing, we still value unfettered lives that lead to unspeakable tragedies over some measure of restraint in current inconveniences could lead to greater pleasures later.

Is it just me, or does it feel, more and more, like we’re in a downward spiral as a civilization. Unlike the collapse of civilizations in the past, this one is global. In Jared Diamond’s Collapse, written over a decade ago, he compares the downfall of various civilizations throughout history, and compiles some main indicators of disintegration:

Is it just me, or does it feel, more and more, like we’re in a downward spiral as a civilization. Unlike the collapse of civilizations in the past, this one is global. In Jared Diamond’s Collapse, written over a decade ago, he compares the downfall of various civilizations throughout history, and compiles some main indicators of disintegration:

- Environmental and population problems led to increasing warfare and civil strife.

- Agriculture was expanded to more fragile areas to feed more people, which eventually collapsed.

- Kings/Chiefs sought to outdo each other with more and more impressive temples.

- The Kings/Chiefs were passive in the face of the real threats to their societies.

He explains further that in collapsing states, leaders will sometimes fail to even try to solve a problem they’re clearly aware of. He argues that they exhibit rational behaviour that becomes entirely self-focused:

Some people may reason correctly that they can advance their own interests by behavior harmful to other people. . . . It employs correct reasoning, even though it may be morally reprehensible. The perpetrators know that they will often get away with their bad behavior, especially if there is no law against it or if the law isn’t effectively enforced. (427)

Yup.

Covid ran a similar course but faster. We cared for a while, then got tired of doing all the things, so it’s been allowed to get worse. Working to help both climate and covid is an uphill battle that appears to be getting nowhere despite more and more articles showing how harmful it is. Recent studies have found that Covid harms immunity for at least eight months after infection, and this lymphopenia is the same thing that causes loss of immunity in AIDS. Covid could be running on the same trajectory as AIDS, starting with flu-like symptoms, then sitting in a latency stage for years, until we see a spate of sudden deaths, and there could be worse to come. Yet we still see pictures of healthcare conferences with few masks in the crowd. We appear to be completely unable to learn from history.

If this is the beginning of the end, then at what point do we call it and start looking into palliative care for our world? Instead of fighting it, should we be looking at a good ending, one that provides necessities and soothes pain and suffering so people can live out their lives with dignity? Because right now, it’s looking like it might be a slaughter. In my province, collective bargaining rights were just deleted with the stroke of a pen. People are outraged and protested in the streets on Friday, but then we came home to find out the Premier decimated protected greenbelt land. The destructive tactics of some politicians come too fast for the public to keep up and continue fighting every little thing, and then they also stay home on voting day. We might just let the world burn until the wifi stops functioning.

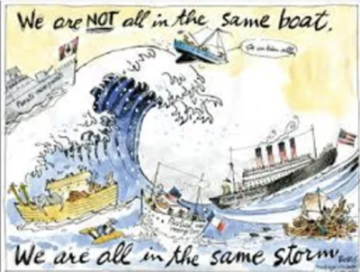

But Covid had a more enlightening effect on a few people. People like me, a white, middle class, mask advocate, are learning first hand and very suddenly what it feel like to be a visible minority in a bigoted society, to be randomly targeted on a bus or leaving a store and followed a bit in order to be called names and harassed. Some think the world has gotten colder and more brutal in tolerating harm to others, but it might be the case that the world hasn’t changed as much as more people, particularly people with a platform, are unexpectedly finding themselves on the wrong side of who matters. Covid has increased the number of people affected by being othered and dismissed. Many people who are racialized, essential workers, unhoused, and/or disabled, have always struggled in ways that were largely ignored.

These little markers of incivility, the shouts in the street, are reminiscent of a story Chris Hedges wrote about in Wages of Rebellion: He describes Marek Edelman, the last survivor of a command that led the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, recounting a pivotal episode in his life before the Ghetto existed. Two beautiful young German officers had taken an elderly Jewish man, sat him on a barrel, and then began to cut off his beard, laughing the whole time. A crowd gathered and also started laughing:

These little markers of incivility, the shouts in the street, are reminiscent of a story Chris Hedges wrote about in Wages of Rebellion: He describes Marek Edelman, the last survivor of a command that led the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, recounting a pivotal episode in his life before the Ghetto existed. Two beautiful young German officers had taken an elderly Jewish man, sat him on a barrel, and then began to cut off his beard, laughing the whole time. A crowd gathered and also started laughing:

It wasn’t a big deal, really. He wasn’t being hurt. He didn’t get cut. He was just being laughed at a little while he was getting an unwanted shave. It’s just a joke. But Edelman understood the important shift that had happened: “that it was now possible to put him on a barrel with impunity, that people were beginning to realize that such activity wouldn’t be punished and that it provoked laughter.”

We’re seeing the inequity loom larger than life with how differently Covid affects the rich and poor. Manufacturing jobs have been hit harder than any other sector in Ontario, accounting for more than one third of all workplace fatalities. Many essential workers have to show up or risk being fired. Many are being badgered to come to work after just five days home when they’re sick with a disease that often takes two weeks to run its course, which increases the risk of infection to co-workers, especially with close contact in poorly ventilated buildings with no protective masks on offer. It’s inescapable under these conditions.

We’re also seeing signs of despair in the number of unhoused people in our cities, some of which have had their homes bulldozed away. According to a MARCO Study Report, the rise in encampments are partially due to the concern with the spread of Covid in typical shelters. Some tiny homes have been built in my region, but not nearly enough for the numbers. In Finland, people are given a small apartment and counselling, and 80% make their way back to a stable life. This is cheaper than just accepting that unhoused people as a collateral damage of a prosperous economy.

And now Canadians are watching as our Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) is being used by people who want to live, but can’t afford to pay their bills. Of the assisted deaths in Canada, 17% cite loneliness as a reason to end their lives. Poverty is intersecting with disability and Covid, exacerbating a health care crisis that was already in the works from labour issues, to create a voluntary genocide. Long Covid will see more disability, with some estimating as at least 10% of people with ongoing symptoms after getting Covid. Over 148 million people have this condition now, many unable to work or even take care of themselves.

Whether we’re nearing the end or not, we need to shore up our healthcare, fight privatization, and implement an ongoing form of CERB: Universal Basic Income. The biggest concern with Canada’s experiment with giving people money to keep them going is that some people made more than they did from their actual income. That’s not a problem with UBI, but a problem with the shocking number of working poor we have in our wealthy country. Some analysts calculate a net cost of about $43-48 billion to eradicate poverty in Canada (Scotti, Hemmadi, Lum), which could be paid for with a 3% increase in sales tax OR crack down on money hidden abroad, OR add another tax bracket of 65% on income over $300,000, OR just add an 8% increase on income tax on income over $20 million /year. One study found that providing money for the poor in a cash lump sum dramatically increased the chance people would move into stable housing and dramatically decreased spending on substances.

Whether we’re nearing the end or not, we need to shore up our healthcare, fight privatization, and implement an ongoing form of CERB: Universal Basic Income. The biggest concern with Canada’s experiment with giving people money to keep them going is that some people made more than they did from their actual income. That’s not a problem with UBI, but a problem with the shocking number of working poor we have in our wealthy country. Some analysts calculate a net cost of about $43-48 billion to eradicate poverty in Canada (Scotti, Hemmadi, Lum), which could be paid for with a 3% increase in sales tax OR crack down on money hidden abroad, OR add another tax bracket of 65% on income over $300,000, OR just add an 8% increase on income tax on income over $20 million /year. One study found that providing money for the poor in a cash lump sum dramatically increased the chance people would move into stable housing and dramatically decreased spending on substances.

It’s possible, if we care enough, to allow everyone to live with dignity until the end. There’s plenty to go around if we can contain our desires for more than we need. That being said, it’s also possible for us to stop climate change and Covid in their tracks! Perhaps a call for memento mori is what’s necessary to shift our attitudes. We need a reminder of the short time we each have here. The natural world is shoving that reminder down our throats if we’re brave enough to pay attention.

If we acknowledge the beginning of the end, maybe we can all slow down. Maybe CEOs will recognize that all this growth is for naught and the rest of us will stop striving for status symbols and trophies and competition for the top place, the way those superficial desires melt away when we found out we just have a few months left. Already in my classes I took out a full unit aiming for depth of understanding over breadth and without homework. People worry about learning loss from the brief times we were in lockdown, but how well can anyone learn if they and their family and friends are coping with loss and treated as if they’re disposable? How much do we need to learn? Maybe we can make do with basic literacy, numeracy, science, history, and geography, then critical thinking and the scientific method practiced over and over to develop profound social-media-literacy: the ability to accurately compare online claims to find some semblance of truth.

This reminder of our mortality shifts our priorities, and that alone might affect problems in education. Illness and death in our midst already is affecting education, making it difficult to study facts and figures and abstract concepts. Grade inflation is so intense now that one guidance counsellor might lose their job for artificially raising a grade to help a desperate student get into university. Students are focusing more on grades than on learning from this same short-term survival instinct that doesn’t measure well. The grades translate to money. Only when students and parents can feel confident they can have their basic needs met without falsifying grades or cheating, can they actually find any enjoyment in learning in our short time together. We want to set them up for jobs of the future, so we make sure they’re computer-literate, but the most important skills might be tolerating extreme temperatures and smoke inhalation.

Far from being panic-inducing, it could help to believe or acknowledge that we’re nearing a collapse situation. Individually, when people accept their own impending death, possessions take less precedence as people. It might be enough to shift us back to community care and compassion and away from capitalist competitiveness. As I work with people to re-instate masks (for instance, by making posters: front and back), I can’t help noticing that the people doing this work all have had a major health crisis at some point in their lives or the lives of a child. We get how fragile we are, how easily we can flip from perfectly fine to chronically ill in a heartbeat.

One set of studies shows that death awareness can improve lives. Reminders of death increase levels of helping, motivates environmental behaviours, provokes peaceful compassion towards members of other groups, and leads to healthier lifestyle choices (smoking less, exercising…). We need to stop the intense striving for more and better, and restore our compassion, community, and contentment. If we can’t get significant action from the top-down, we might be able to change our individual attitudes enough to make a cultural shift from the bottom-up.

In the hopeful ending of his book, Jared Diamond calls for leaders with courage to take bold steps:

In the hopeful ending of his book, Jared Diamond calls for leaders with courage to take bold steps:

Such leaders expose themselves to criticism or ridicule for acting before it becomes obvious to everyone that some action is necessary. . . . We should admire not only those courageous leaders, but also those courageous peoples . . . who decided which of their core values were worth fighting for, and which no longer made sense. (439-40)

Fortitude, wisdom, temperance, and unfettered compassion. Those are the real basics we need for this final chapter.