by Rebecca Baumgartner

Parenting is one of the domains where certain people scoff at the idea that reading a book or article could possibly be helpful. “That’s nice and all,” the complaint goes, “but when it comes to real life, all those ideal scenarios fly out the window.” The other group of parents, the ones who gobble up data and theories about child development, feel that any tool or strategy that gets us closer to being the parent we want to be is worth investigating.

I have fallen into both camps at various times, and I have found it largely depends on the writing skill of the author and the explanatory power of their ideas – but most of all, whether they offer anything genuinely new or perspective-shifting that I couldn’t have figured out on my own amidst the grunt work of being a parent.

A recent NPR article encapsulates the rising industry of telling us what we already know under a trendy label and repackaging common sense as something newsworthy. Starting with the headline of the article – “The 5-minute daily playtime ritual that can get your kids to listen better” – we are already off to a bad start.

The article discusses the concept of “special time,” which is open-ended playtime where the parent is not telling the child what to do for at least five minutes. This approach is described as a “counterintuitive” concept invented by a specific researcher in the 1970s. It turns out that if you listen to your kid, engage with them as a person, aren’t always barking commands at them, and play with them in a way they find satisfying, they will – wait for it – like you better and be more willing to listen to you. Perhaps shockingly to the researchers, this is solid advice for dealing with pretty much all humans, despite their claim that “the practice often feels awkward for adults at first.” Read more »

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

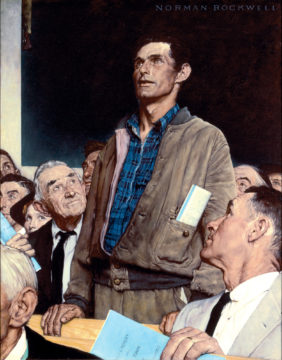

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.)

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.) Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).