by Ada Bronowski

The weird and wonderful painter Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), whose most famous work is undoubtedly The Nightmare from 1781, presents an interesting case of dysmorphia. The Nightmare is as disturbing as it is entrancing with its undercurrents of erotic terror and dreamy fantasy, but its surface horror is perhaps not what is most shocking about it. What if the artist’s self-portrait was lurking somewhere across the horse and the goblin?

Neither a historical scene, nor an illustration of a literary reference, the subject-matter of The Nightmare is entirely made up, which, in its 18th century context, makes it rather unique and draws alarming attention to the mind from which it came. Over the same period, Füssli drew a number of self-portraits which, when confronted with portraits of the artists made by others, betray a notable distance between the way the artist appeared to others and the way he saw himself. In a neat and well-rounded Paris exhibition, Füssli: Entre Reve et Fantastique, currently on show at the Musée Jacquemart-André, a few concentrated rooms spin a twisted tale around the windmills of the artist’s mind.

Füssli made his career in England, but he was born in German-speaking Switzerland and spent the formative years of his youth travelling through Europe, settling for a period of eight or so years in Rome. Ordained as a pastor at age twenty, his penchant for provocation and a passion for art kept him away from the pulpits all his life, to end up as Keeper and professor of drawing at the Royal Academy in London.

Füssli was evidently drawn to the lugubrious and fantastical: his works are of mythological scenes where sea monsters are decapitated by brave heroes while gods look on from afar, or of Shakespearean ghosts – Hamlet and Macbeth are his favourite plays as he painted any scene with a ghost in it or ghost-like sublimations like his rendering of Lady M., whose madness turns her into a specter before her time. But he even manages to make Beatrice from Much Ado about Nothing look demonic. The intelligence of the show’s curators (Christopher Baker, Andreas Beyer and Pierre Curie) is to allow for this fandango of the eerily fantastical to unfold under the aegis of a first room devoted to the portraits and self-portrait of the artist. Thus a series of stately portraits of a well-to-do, rosy-cheeked and congenial Füssli, painted by contemporaries, are placed in dialogue with the drawing of a pre-phthisic self-portrait.

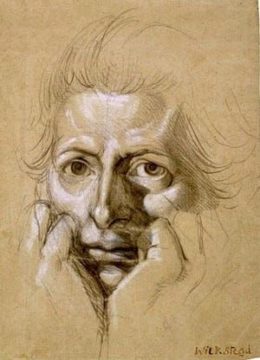

It is hard to miss the incongruity between the way Füssli represents himself and the way others portray him. Comparing the portrait by colleague and rival James Northcote (1746-1831) and the self-portraits made in the same years, we note enough similitude to see that Füssli and his portraitist capture the artist’s distinctive facial traits: the rather big nose, the sunken eyes, a high forehead – all traits that the other portraits shown in the room sustain as evidently true to reality. But where the portraitist paints big eyes, Füssli sees bulging eyes. Where the portraitist paints depth and reflexivity in a penetrating stare, Füssli sees a huge anxious stare, aghast with haunting visions; a mouth that keeps shut for want of screaming; a face that would rather hide behind the hands, but for the mirror the sitter is looking at, horrified at what he sees in it. It is the shock-glare of self-recognition that Füssli’s self-portrait imparts to us, the prying spectator, as he stares straight at us as if we were on the other side of the mirror.

And so Füssli is at once the commanding and charismatic man his portraits show: a sociable man ready for and capable of action. But from the inside, he is the tormented, restless character that peers outwards with difficulty and even fear. It is the practice of self-portraiture that is subverted with Füssli, as if he expresses in drawing one of the messages of his revolutionary times: that your internal life counts, that you are not only, and perhaps not at all, what the others see.

Over a hundred years later, Oscar Wilde would make this call his creed: the only aim in life should be ‘self-realisation’, an enterprise Wilde transformed into the only one worthy of the artist, though it should condemn him to travel to the worst of places: ‘people whose desire is solely for self-realisation never know where they are going.’ That unknown destination in Wilde as already and perhaps, first, in Füssli passes through the darkest depth where horror taints every erstwhile pure thought.

With Füssli, perhaps because he is a pioneer, treading outwards in a world still high on its rediscovery of Classicism, self-realisation begins with plumbing the depth of self-portraiture and over-turning its signification.

From the early self-portrait from 1459 of Benozzo Gozzoli from within the throng of the procession of the Magi in the Palazzo Medici in Florence, to the self-portraits of Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), the tradition of the artist’s self-portrait is to declare his or her status as a painter with a painter’s panoply. It is a familiar stance from Albrecht Dürer to Diego Velazquez: ‘I did this’, the artist’s face is telling us and their eyes burn holes into ours to make sure we get the message. When Dürer read in Pliny that the first Greek painter Apelle used the imperfect to declare his authorship, he swapped the usual Latin past perfect tense ‘fecit’, (Dürer made this) to the imperfect ‘faciebat’ (Dürer was doing this). The switch of course opens the doors to the question of time and it would be remiss of us to not mention the greatest self-portraitist of all times, Rembrandt (1606-1669) whose indefatigable examination of his evolving appearance has left us with one of the greatest meditation on the instability and frailty of the body through time.

But Rembrandt’s self-portraits paint the figure in the mirror. Füssli paints beyond the mirror, a projection onto the mirror of the way his mind sees his body.  It is a curious interpretation in reverse of the other great theory of self-portraiture, which is the idealisation of the self. An escape route from the scars of time which 18th century Classicism had formulated in particular through the voice of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), the first great theorist of classical beauty for our modern times. Füssli knew his work well since he translated into English Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Sculpture and Painting in 1765 – all the better however, to explicitly rebel against the core Winckelmannean idea. That the artist should create a physical beauty to match the inner virtue and beauty of the soul. There is no such thing, Füssli discovers, first and foremost in delving into his own. The Platonism inherent in Winckelmann’s understanding of the beauty of classical art is, in Füssli’s own words, ‘frigid’ and ‘a dream’. Coming from a man whose works are racked with the echoes of dreams, we must understand here that for Füssli, there are dreams, and then there are dreams. The dream of classical beauty is naff. The dreams populated by monsters and goblins, now those are the dreams.

It is a curious interpretation in reverse of the other great theory of self-portraiture, which is the idealisation of the self. An escape route from the scars of time which 18th century Classicism had formulated in particular through the voice of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), the first great theorist of classical beauty for our modern times. Füssli knew his work well since he translated into English Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Sculpture and Painting in 1765 – all the better however, to explicitly rebel against the core Winckelmannean idea. That the artist should create a physical beauty to match the inner virtue and beauty of the soul. There is no such thing, Füssli discovers, first and foremost in delving into his own. The Platonism inherent in Winckelmann’s understanding of the beauty of classical art is, in Füssli’s own words, ‘frigid’ and ‘a dream’. Coming from a man whose works are racked with the echoes of dreams, we must understand here that for Füssli, there are dreams, and then there are dreams. The dream of classical beauty is naff. The dreams populated by monsters and goblins, now those are the dreams.

Name of the dream: the nightmare. In his most famous painting, the head of an insane dark horse appears thrusted into the scene from a darkness behind, it is a black mare and thus mistakenly got associated with the painting’s title – though all good etymologists know that the word ‘nightmare’ has nothing to do with a female horse, but the medieval name of a night demon, as the old German Nachtmahr attests. The inner life of the artist is a nightmare as Füssli’s self-portraits tell us. Self-representation must pass through this realisation: that the soul is traversed by visions that put the idealised dialectic between virtue and vice far away from the concerns of the artist. Idealised beauty is a gimmick. Though Füssli’s works are often affiliated to the sublime, an examination of his art as the result of an irreconciliation between his external representation and his self-representation shines a different light on his production, which is torn between the deep and the ridiculous.

– though all good etymologists know that the word ‘nightmare’ has nothing to do with a female horse, but the medieval name of a night demon, as the old German Nachtmahr attests. The inner life of the artist is a nightmare as Füssli’s self-portraits tell us. Self-representation must pass through this realisation: that the soul is traversed by visions that put the idealised dialectic between virtue and vice far away from the concerns of the artist. Idealised beauty is a gimmick. Though Füssli’s works are often affiliated to the sublime, an examination of his art as the result of an irreconciliation between his external representation and his self-representation shines a different light on his production, which is torn between the deep and the ridiculous.

Because there is something indelibly ridiculous in the self-portraits: the bulging eyes and the long nose make Füssli look somewhere in between Søren Kierkegaard and the Hobbit. The hands add a posing, or poseur, counter-effect to the fearful facial traits. And what is Füssli so afraid of? Of what he sees, we might say; but what he sees, is himself. The hands, the eyes, the sly look at us through a looking-glass… but these are the traits of the nightmare-goblin of The Nightmare.  It is not too far-fetched to recognise another self-portrait in the goblin that sits so complacently on the chest of the sleeping lady: the same huge puffy-eyed glare that fixes the onlooker, the same hand that wants to but does not hide the face. As a back-up almost, the horse-head, the dark mare, that Füssli added at a second stage of the elaboration of the painting reiterates the rolling-eyed stare; this time, the big nose has morphed into an equine muzzle.

It is not too far-fetched to recognise another self-portrait in the goblin that sits so complacently on the chest of the sleeping lady: the same huge puffy-eyed glare that fixes the onlooker, the same hand that wants to but does not hide the face. As a back-up almost, the horse-head, the dark mare, that Füssli added at a second stage of the elaboration of the painting reiterates the rolling-eyed stare; this time, the big nose has morphed into an equine muzzle.

If the artist sees himself as a goblin, should we trust him that he is one? Not more than we should trust what we see of him, from outside as it were, through Füssli’s portraitists. Both visions are equally true and equally false. Füssli’s works of self-representation reveal his decisive step into a modernity made up of equal parts realism and self-deprecation. His realism is still charged with theory, that is, the idea that what is real is what is true – it is not by chance that amongst the effervescence of Enlightenment intellectuals whom he encountered whilst staying in Paris in the 1760s, he was attracted to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the more marginal of the group, and fanatically puritanical in his aesthetic judgements. It is Rousseau who complains, via his protagonist, Saint-Preux, in his novel, The New Heloise from 1761, that portraits that too superficially resemble the sitter miss all their inner complexity. Füssli’s tendency to realism is a commitment to stay faithful to one’s inner sentiments.

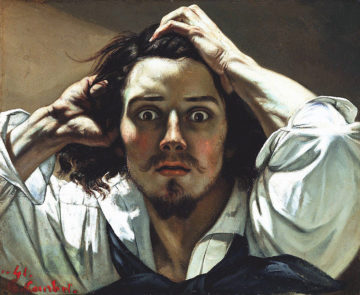

His heir in this exploration is most likely to be found in Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) who explores self-representation precisely through a sensuous multiplicity of inner passions.  Courbet’s self-portrait as The Desperate Man echoes the emphatic hand-language Füssli invents. But where Füssli retracts inwards to the monstrous within– the goblin in him is a-calling – with a direct apologetic look to us, Courbet paints himself as facing a monster outside of him. His eyes are directed at a point just out of the frame which we could see as well if only we tip-toed over a little more. The monster is between him and us.

Courbet’s self-portrait as The Desperate Man echoes the emphatic hand-language Füssli invents. But where Füssli retracts inwards to the monstrous within– the goblin in him is a-calling – with a direct apologetic look to us, Courbet paints himself as facing a monster outside of him. His eyes are directed at a point just out of the frame which we could see as well if only we tip-toed over a little more. The monster is between him and us.

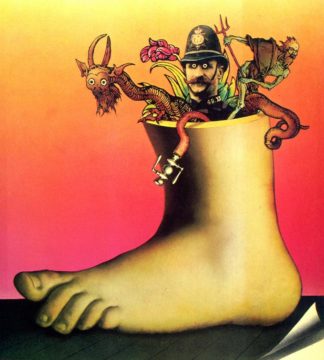

Another self-representation of Füssli’s is The Artist’s Despair Before Ancient Ruins. Again it is the arm and hand gesture that prevent us from taking this self-portrait absolutely seriously. The artist’s minute proportion compared to the enormous foot recognisable as the remnants of the monumental, 12-meter high statue of Constantine, instead of being tragic is in fact, funny.  As Andreas Beyer in the show’s catalogue notes, the very name of the artist, Füssli, means in German, ‘little foot’ and it is with a self-deprecatory pathos that Little-Foot does not even try to compete with Big-Foot.

As Andreas Beyer in the show’s catalogue notes, the very name of the artist, Füssli, means in German, ‘little foot’ and it is with a self-deprecatory pathos that Little-Foot does not even try to compete with Big-Foot.

If the sublime, as it was conceived by Longinus in antiquity and Edmund Burke in 1757, occurs in the clash between an overpowering emotion and what escapes the possibility of measure, then we see how Füssli is not a painter of the sublime. He is a painter of the satire of the sublime, the grotesque of disproportion. Rather than greatness, he paints impossible angles, usually from below at a vertiginous oblique to the effect, not of terror but of the preposterous – no wonder that, after being forgotten for a century, it is the Surrealists who first rediscovered him. But perhaps his more truthful disciples in the marriage of the fanciful and the grotesque, anxiety and ridicule, are the Monty Pythons. It is a small step for a foot, but a significant one for modern man to go from crying in despair beside Big-Foot to being crushed by Monty Python’s signature Big Flying Foot.