by Thomas Fernandes

In the natural world, predation may mark the end of life, but it doesn’t signal the end of ecological interactions. The hunt, with all its challenges and shifting interactions, is not an end in itself, it only creates the opportunity to feed. O nce the kill is made, two main strategies emerge: feeding quickly and leaving, or holding on to the remains for a few days to draw multiple meals from them. The carcass, meanwhile, becomes a contested prize, attracting stronger competitors seeking a free meal, blurring the line between hunter and scavenger. Solitary cheetahs, for instance, lose nearly half their kills to lions and hyenas. After this struggle, as time and heat accelerate decomposition, the remaining flesh soon turns inedible to most animals. From that inedibility emerges an opportunity for species able to thrive on what others must abandon. Scavenging, in this sense, occupies a shifting niche, rich in energy but scarce and unpredictable, a prize that few species can afford to rely on.

Among vertebrates, vultures stand alone as obligate scavengers, living almost entirely on the flesh of the dead. This diet exposes them to hazards that most animals evolved to avoid through evolutionary adaptations: pathogens, toxins, and chemical byproducts from decaying tissue. Humans, too, evolved pathogen avoidance, a behavioral response that manifests as disgust toward bodily fluids, rotting meat, or anything in contact with them. By association with the unclean, vultures are generally portrayed as vicious and malevolent, or simply ignored, despite their endangered state: 11 of the 16 species of African and Eurasian vultures are classified as Critically Endangered or Endangered, according to the IUCN Red List. Observing vultures challenges both our innate disgust response and our understanding of how scavengers adapt to extreme diets.

When we think of vultures, we imagine a single bird, when in fact they encompass a surprising diversity. There are two distinct vulture lineages that diverged 69 million years ago: New World vultures in the Americas and Old-World vultures in Africa, Europe, and Asia. The Old-World vultures tend to eat larger carcasses, including large ungulates such as hippopotami, horses, and buffalo. New World vultures, in contrast, feed on smaller prey, such as monkeys, rodents, and birds.

These two categories are further divided into guilds which determine feeding order and interactions, reminiscent of grazing hierarchies in the savanna. Guilds represent an evolutionary solution to the challenge of limited carrion, subdividing carcasses to reduce competition and maximize energy extraction. From this structure emerge three main feeding guilds, each specialized to exploit a particular portion of the dead animal, leading to differences in body mass, beak shape, and neck musculature.

Rippers, such as the White-headed vulture (Trigonoceps occipitalis), feed on tendons and tough meat. Their large beak, sometimes strong enough to tear open the fresh hide of a dead elephant, rhinoceros or hippopotamus allows them to expose muscle and viscera. These are the largest types of vultures weighing up to 13 kg, their large mass giving them leverage to tear flesh but also to fight off competition. At a fresh carcass, rippers first work to pry open the tough hide of a recently fallen buffalo or zebra, their powerful beak tearing flesh and spilling blood.

Gulpers, like the Indian vulture (Gyps indicus), compose the largest group, with long, bare necks and slender skulls. Their gutter-shaped tongues, lined with backward-pointing spikes, help them pull out viscera efficiently. They often arrive at remains already opened by rippers or predators, using their specialized anatomy to exploit any opening for deep extraction of soft tissue. If no openings exist, they must wait as decomposition gradually softens the hide and connective tissue, allowing them to reach the viscera on their own.

Scrappers, like the Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus), are smaller. Their slender beaks are unsuited for tearing hide but allow precise foraging of tissues, skin fragments, or scraps left at the edge of a carcass. They often hover carefully among larger scavengers or near human activity, picking at remains that others overlook. The Egyptian vulture is one of the few birds known to use tools: Because their beak is too small to crack an ostrich egg, they resort to dropping stones onto the eggs to break them open.

Outside of these guilds, the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) is uniquely specialized as the only known vertebrate bone-eater, with a diet consisting of 90% bones. This specialization gives it access to an unchallenged and long-lasting food source. They can detect and select the most nutritious bones and swallow them whole, up to 28 cm. Using their extremely acidic stomachs, they dissolve the calcium-based mineral portion to access marrow. Larger bones are broken by dropping them onto rocks, sending shards scattering across favored ‘ossuaries’ often located near their nests. These sites get their name not only from the bone-breaking activity but also from the layers of bones that accumulate over time, some of which can serve as temporary storage, like a pantry. Even its sense of taste sets it apart from other vultures. While most vulture species have reduced bitter taste receptors to make carrion palatable, the bearded vulture retains full sensitivity (Xiang, 2025).

Despite their diversity, vultures share strikingly convergent traits, from lineage millions of years distant and oceans apart. Perhaps the most salient is their ability to resist infections from the very carcasses they feed on. While earlier explanations emphasized acidic stomachs, bare heads, urohydrosis (peeing on their legs) and robust immune systems, recent studies paint another picture. One in which the key lies in alliances with microorganisms and highly targeted immune adaptations.

Their facial skin, constantly exposed to decaying flesh, confronts bacteria, fungi, insects, and toxic or carcinogenic compounds. Remarkably, 528 bacterial taxa have been identified on vultures’ facial skin, compared to around 150 on human skin, reflecting their extraordinary microbial exposure. A first line of defense is tough, keratinized skin, but much of the protection comes from a specialized skin microbiome. Their skin microbiome hosts specific bacteria that provide multiple services, including producing insecticides, antifungal compounds, biosurfactants (broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity), and antibiotics; forming protective biofilms; and degrading harmful chemicals such as naphthalene(Lobello et al., 2025). In addition, cutaneous microbes degrade sebum, releasing fatty acids that raise pH and limit bacterial growth.

Perhaps most counterintuitively, vultures possess genes that suppress the inflammatory response to bacteria. Rather than fighting every microbial invader, their tissues are protected from the damage that would normally result from mounting a full-blown inflammatory reaction to such a massive microbial load.

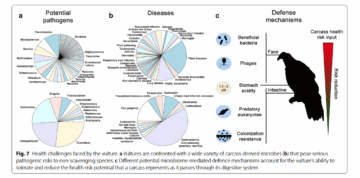

After eating, vultures face the dual challenge of digesting carrion and suppressing pathogens. Their digestive microbiome is dominated by two anaerobic bacterial families commonly found in soils and rotting meat: Clostridia and Fusobacteria. Some strains in these groups are deadly to other vertebrates, producing toxins such as those causing botulism and tetanus. In vultures’ gut, only select strains thrive, those that both break down protein and fat into nutrients the bird can absorb and produce antimicrobial substances that inhibit dangerous bacteria, like Salmonella, while also outcompeting others for resources.

Vultures’ immune adaptations complement this microbial alliance instead of acting as a blanket defense. Rather than attacking all microbes, it selectively neutralizes vertebrate-targeted toxins (like botulism) while tolerating harmless or beneficial ones. Additional protection comes from other microorganisms in the gut which do not aid digestion but help suppress harmful bacteria. Like bacteriophages, which are viruses that specifically target certain bacteria. They insert their genetic material into the host, hijack the bacterial replication machinery, and multiply until the bacterium bursts, releasing many new phages in the process, all looking for a host. Through this ecosystem, of the initial 528 bacterial types found on the skin, only 76 persist in the vulture’s gut. Far fewer than the 500–1,500 typically needed in humans to digest a varied diet. This number underscores the extreme specialization needed for a diet of carrion.

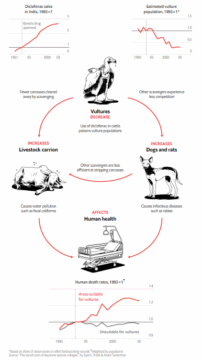

By consuming decaying meat, vultures perform a critical ecological service: they limit the growth and

spread of diseases that might otherwise proliferate in decaying carcasses. Their ability to outcompete other, less-protected scavengers, such as rats, amplifies this effect. Yet this ability comes at the cost of a restricted diet that leaves them vulnerable to any reduction or contamination of their food supply. Vultures are not invincible “pathogen vacuum cleaners”. Their immunity depends less on overall strength than on precision, microbial partnerships and toxin-specific responses that work brilliantly against known pathogens but fail against unfamiliar contaminants. One such contaminant proved catastrophic: the veterinary drug diclofenac.

Diclofenac is a veterinary drug used in India. Even minimal residues of diclofenac overwhelm vultures’ physiology, which lacks the renal capacity to metabolize the drug. When treated cows die, their carcasses become a death trap for unsuspecting vultures. Diclofenac use in India caused vulture population declines by up to 90%, with downstream consequences for disease management and human health.

Much attention has focused on vultures’ ability to handle pathogens, their primary ecological role, but this perspective tells only part of the story, leaving many questions unanswered. Another challenge defines the obligate scavenger: surviving on a patchy and unpredictable food supply. The next essay will explore this challenge, asking why the only vertebrate obligate scavenger takes the form of a vulture, and casting its bald head and acidic stomach in a new light.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.