by Thomas O’Dwyer

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

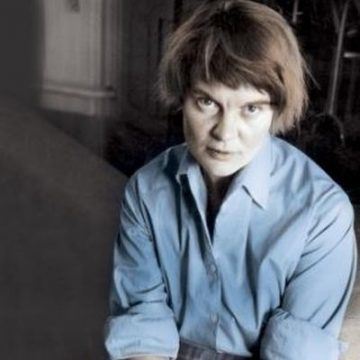

Dame Iris Murdoch would be 100 years old this July 15 if she had lived to celebrate it, but her brilliant mind faded away in the fog of Alzheimer’s disease and she died twenty years ago in 1999. A recent article in The New York Times lamented that her reputation has also faded with time. “Distressingly, her posthumous reputation is in semi-shambles. Many of her novels are out of print. Young people tend not to have read her. She is seldom taught,” wrote Dwight Garner. Literary reputations are like the actors on Shakespeare’s stage of life, they have their exits and their entrances, but unlike the actors, they can be born again. It is difficult to say if Murdoch’s star is set to rise any time soon. Like many of her 20th-century contemporaries, her novels can seem as ancient as the Victorians. They live in a lifetime before digital watches, never mind computers and the rest of our electronic universe. Few of her characters in their whiteness, snobbery, and obtuseness are people we would find dominant in the streets or cafes of London today.

Those of us who are old enough to have lived in those seedy European middle-class days will probably remain drawn to writers like Iris Murdoch and novels like Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, just as our grandparents clung to Proust and wordy Victorians with their whiff of lavender and lilac. The reason I promised myself at so young an age to reread Under the Net was simple – most of the book sailed over my head and I had no idea what it was about. That is to say, I had no idea what the author meant to tell me. But I found it captivating enough to form my first impressions and it did dovetail into some of my interests at fifteen. I thought the book was mainly about friendship – something I valued because I had to fight for it. During my childhood in rural Ireland, my domineering mother rejected any friends I brought home. Her reasons were arbitrary and controlling – they were simply “not good enough,” their backgrounds never fitted in with her vague and unjustified delusions of grandeur. But at fifteen and midway through secondary school, I had several good friends and fiercely defied mother’s disapproval to keep them.

When I opened Under the Net, the first sentence nailed it. “When I saw Finn waiting for me at the corner of the street I knew at once that something had gone wrong. Finn usually waits for me in bed, or leaning up against the side of the door with his eyes closed.” Someone faithfully hanging about and waiting for his friend to return. I at once became the protagonist, Jake Donahue, and my best friend Doc (his nickname will suffice), became the novel’s Hugo. The friendship theme was reinforced as the developing relationship between Jake and Hugo mirrored the intense if ill-informed “philosophical” arguments I frequently had with Doc and which continued for a few years into our bohemian student life in Dublin. Finn was Michael, a vaguely mysterious other friend of mine. There was also Mr Mars, a dog, the universal symbol of the best friend.

I had no idea what the plot was about – Jake and Finn had adventures, Jake, Hugo and Dave had conversations, Mars frolicked aimlessly in and out of the later chapters. There was an old lady in a small shop, surrounded by cats. There were some other females, as unimportant as sisters. I skipped pages that seemed filled with non-sequiturs beyond my understanding. Jake wrote a book called The Silencer based on his conversations with Hugo. A lengthy quotation from it was incomprehensible to me. I promised myself that when I was an adult, I too would write stuff no one could understand. That would be so clever. Iris Murdoch would be my best friend forever.

What a difference fifteen years make in a young life. The rural schoolboy had vanished into the Celtic mists of time; at 30 I was now a Royal Air Force officer, five years married, with a four-year-old daughter. We were packing up house before a posting to Cyprus when, as if on cue, Under the Net fell from a stack of books waiting to be stored. Yes, that would pass the time on the flight. What a difference fifteen years make to an old book. I remembered almost nothing of it – a vague recollection of cavorting friends and a dog, as purposeless as childhood itself. I began to feel it might be an odd choice of book for a married adult and wondered if I should hide it in a newspaper lest anyone see me reading it. But this is Iris Murdoch.

As I turned the first pages, I was shocked to discover that Jake was not so much a free artistic spirit as a feckless freeloader, scrounging accommodation and money from his friends, expecting a previously abandoned girlfriend to be waiting for him when he returned from his travels. At fifteen, how I had identified with this jerk? He was a hack translator too lazy to write something of his own, too immature to love a woman responsibly. Worst of all were the friendships and weighty conversations I had so admired. Jake had actually appropriated their philosophical conversations without Hugo’s permission and published them under his own name as The Silencer. I was amused to find that the only constant that remained from my teenage years was that the excerpts from The Silencer were still incomprehensible. But one of them did reveal the meaning of the book’s title, which I had never considered.

“All theorizing is flight. We must be ruled by the situation itself and this is unutterably particular. Indeed it is something to which we can never get close enough, however hard we may try as it were to crawl under the net.”

At another point, Hugo says, “the whole language is a machine for making falsehoods.” So, the “net” is the tangle of abstraction and generalization that characterises language itself and from which the book’s characters struggle to extract meaning. Iris Murdoch was first a philosopher, then a novelist. She was highly regarded as an academic philosopher in Oxford and London and had published several books and essays, including Sartre: Romantic Rationalist, before she turned to fiction. Her interest in Plato and the pursuit of “the good” as a moral necessity resonates in her novels. Under the surface of the Net runs a powerful current of philosophical musings.

The novelist Murdoch eventually eclipsed the philosopher, and after her death, both these achievements seemed to fade from academic and public perception. Her last appearance in the spotlight was in 2001, in the film Iris, starring Kate Winslet as the young Murdoch and Judi Dench as the older. It was adapted from the memoir of her husband, John Bayley. But there are signs that her groundbreaking work in moral philosophy might be ready for rediscovery. This should be helped by the universal reassessment of women’s historic contributions to science and culture that have been buried under layers of patriarchal distain.

Murdoch always proclaimed herself a champion of Plato and in her writing she gave force to the reality of the Good and asserted that a moral life is a pilgrimage from illusion to reality. The American philosopher Martha Nussbaum has said that Murdoch “had a transformative impact on the discipline of moral philosophy.” Others highlight fundamental aspects of her philosophy, including moral naturalism, attention to human virtues and emphasis on the need to identify and see moral facts.

In my adult reading of Under the Net, the women characters Sadie and Anna, whom I had almost entirely failed to notice, leapt off the pages as complete characters. And then there was the plot – such as it is – of which I had little?

awareness. I remembered some farce involving a bookmaker and a kidnapped dog, a plot to steal one of Jake’s translations and sell it to a Hollywood movie mogul. I recalled how Jake and Hugo had their first conversations on philosophy and socialism at a common-cold research centre, and their last one at a hospital bedside under strange circumstances engineered by a malign fate.

The book is often tagged as a “light comic novel,” though more than one critic has failed to be amused. Murdoch said her ideal reader was “someone who likes a jolly good yarn and enjoys thinking about the book as well as about the moral issues.” She said in later years that Under the Net embarrassed her because she thought the writing was immature – but any struggling writer could only aspire to achieve such a level of immaturity. Many critics still consider it to be one of her best works and it is listed in Random House’s top 100 novels of the twentieth century. She went on to write twenty-five more novels, as well as several books on moral philosophy.

Murdoch identified herself very much with her protagonist Jake – “a failed artist and picaresque hero” – at the time she wrote the book. Murdoch was born in Blessington Street in Dublin, a run-down inner-city area in the unfashionable northside of the river. The residents, claiming various occupations and religions, would have been described as poor but genteel. She would not have remembered it, as her parents moved to England when she was a child, but that didn’t stop her describing it, accurately, as “a wide, sad, dirty street, with its own quiet air of dereliction, a street leading nowhere, always full of idling dogs and open doorways.” That has echoes of the poet Louis MacNeice’s image of a poor Dublin street with its “bare bones of a fanlight / Over a hungry door.”

It is the same atmosphere of genteel decay and often delusional struggles for artistic success or wealth that permeates Under the Net. Jake, the lazy translator of cheap French novels, is always broke and begs shamelessly from his friends, none of whom seem to complain or hold it against him. He tries to repair past mistakes by reconnecting with his former girlfriend Anna Quentin (and her actress sister Sadie), and his old friend Hugo Bellfounder, a mild-mannered philosopher. Jake is ashamed of how he had misinterpreted his discussions with Hugo to boost his own ego and published them without telling his friend. The plot develops through a series of adventures involving Jake and his offbeat sidekick, Finn. From the kidnapping of the movie-star dog, Mr Mars, to the staging of a political riot on a movie set, Jake attempts to remake his life as it revolves around his persistent misreading of the intentions of others.

The story ends more or less where it began, although Jake has lost all his friends, except for the dog he is obliged to buy with his last 700 pounds. There is however a hint that he may be at last on the verge of becoming a real creative artist – just as Under the Net launched the aimless and relentlessly promiscuous young Murdoch on her literary career. There is remarkably little explicit sex in Murdoch’s novels, though there are multiple complex affairs. But love is everywhere. One critic commented that love affairs were to Murdoch like the sea was to Joseph Conrad, and her tales are infused with the never-ending search for that Platonic good, the perfect relationship. Martin Amis wrote: “Her world is ignited by belief. She believes in everything: true love, visions, magic, monsters, pagan spirits. She doesn’t tell you how the household cat is looking or even feeling; she tells you what it is thinking.”

One may read Under the Net as a tale of a crazy artist misunderstanding the messages of serendipity, or in an existential battle with the absurdity of life. The novelist A.S. Byatt wrote that in this novel, Murdoch is having a philosophical debate with Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea. In Sartre’s novel, the protagonist Roquentin finds life to be meaningless, existence is a contingency without aim or explanation that is imposed on individuals without their consent. Early in Under the Net Jake observes: “Everywhere west of Earls Court is contingent, except for a few places along the river. I hate contingency. I want everything in my life to have a sufficient reason.” A.S. Byatt was on to something about Murdoch’s intent, especially where she puts these words in Hugo’s mouth: “There’s something fishy about describing people’s feelings. All these descriptions are so dramatic; things are falsified from the start.”

Murdoch is silencing Sartre on the meaninglessness of existence. Words cannot be used to generate babble about existence. It is not something which should be generalized and discussed through useless language. It must be experienced individually and lived as it is revealed – a firm return to Aristotle’s belief that it is our actions that define our lives. Murdoch may have written greater novels than this – The Sea, the Sea, which won her the Booker Prize or The Severed Head, which was much loved by critics and readers – but rarely has a first novel been so skillfully crafted and endured for so long. Under the Net cast the first Murdoch spell that so many of her readers have been happy to live under for all these decades.