by Brooks Riley

Ems, 17 June 1880

“This morning I took a long walk with Papa . . . judging by this morning, a more awfull profusion, diffusion, infusion and confusion of colours it is difficult to imagine . . . the Britishers especially excell in this art and their colours are put together as they might be on the dirty palette of an inexperienced painter.. . .”

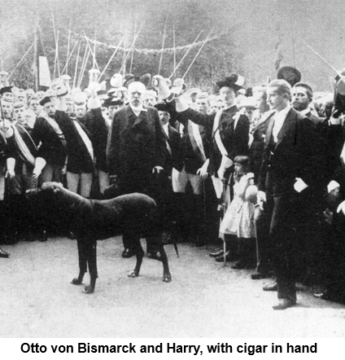

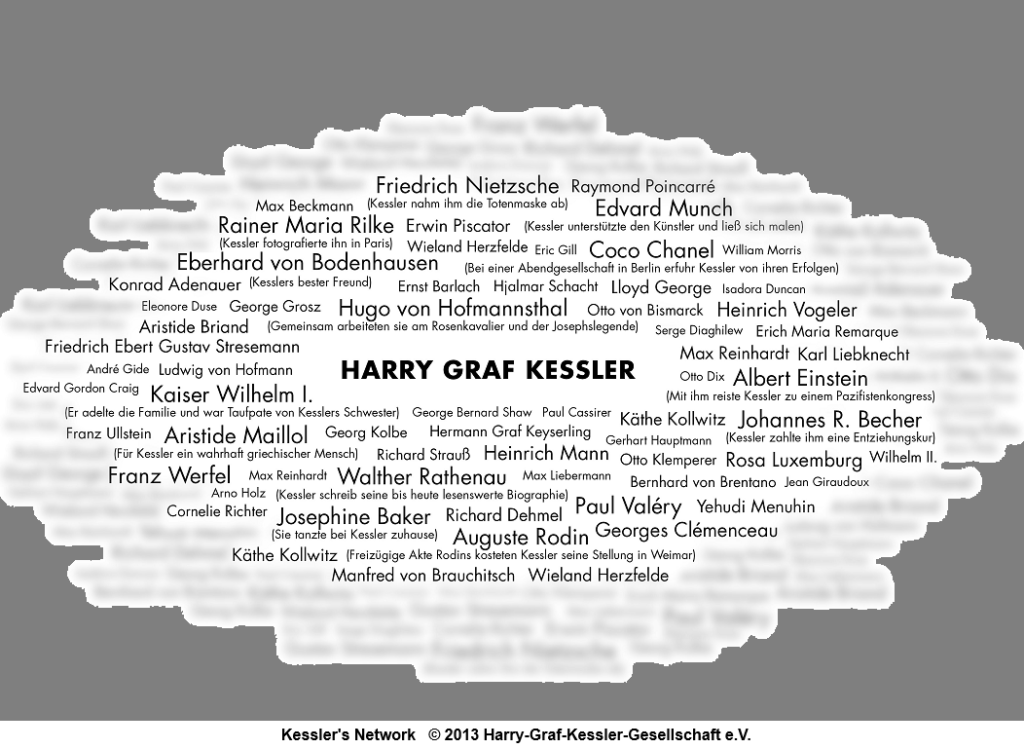

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

“. . . the promenade is a crowd of dresses so short and tight one might take them for underpetticoats or so long and loose you could mistake them for dressinggowns, of cloaks most certainly copied from the assyrian bas reliefs or from the cloaks found with the mummies in the pyramyds (with which they have a strong resemblance,), . . . of projecting stomacks, of very flatt and long feet, of red faces and other accomplishments. . .”

Nota: In coming to Ems we had 19 trunks and 18 parcels in the whole 37 things, Rien que çà!

Harry takes a walk with his Papa, but he won’t tell us what they talked about. What matters to Harry is reporting what he saw on that walk and how he saw it—as journalist, critic, satirist, diarist and outsider. His nota, thrown in for fairness, adds his own family to those guilty of excess.

In this opening salvo, we learn that beyond the omniscience of his observations, Kessler is not terribly interested in writing about himself. The less he tells us, the more we want to know about him. The less he tells us, the more we will start to feel that we know him, warts and all, as the mists around his persona slowly begin to lift. It is this indistinct but discernible sum of a man who will become as fascinating as the many famous people he writes about during his whirlwind European lifetime. At ease in five languages (two of them dead), he manages to combine a phenomenal intellect with the social ease that made him a lively addition to any dinner party.

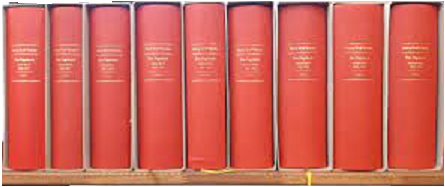

Reading Kessler’s 10,000-page magnum opus is like going down a rabbit hole that suddenly opens up into a gigantic cavern with dozens of tunnels going off in all directions, to be entered at one’s peril. Stopping to research someone he mentions will only lead to further excursions into the madding crowd of leading players, with surprising twists and turns that make our own age seem far too homogenous and predictable. One can get lost in that cavern of experiences, where art, politics, science and philosophy overlap, and where the good, the bad, and the scandalous mingle merrily in the shadow of the coming storms.

Harry will rarely again be as garrulous as he was in 1880. Even before he reverts to German after 11 years of English entries, he learns how to devastate with a single phrase, only occasionally resorting to paragraphs to skew his victims. But when he does take aim, he is an equal-opportunity sniper against bad taste, parvenu behavior and stupidity. Even the Krupps are not spared, or the Kaiser.

“Chairs giving off airs like old maids so that you hardly dare to sit on them; flowered carpets, straining to find admirers, as if they wanted to monopolize the entire conversation in the room; bell pulls presuming the importance of a painting. . .” [a critique of Heinrich Vogeler’s Art Nouveau interior designs]

He participates in the diary as an interlocutor in conversations with others—an additional format for exposing his own thoughts on a subject. His powers of description and the insightful thumbnail psychological profiles of the people he meets, form a vivid and astonishingly modern approximation of La belle époque and Weimar eras—and of the realities behind the myths. The cast of exotic personalities crowding Kessler’s dance card reads like a who’s who of European culture and society.

The further one travels along his timeline, the more Kessler surprises. Beyond the witty barbs, he is actually kind, generous to a fault, open-minded, adventurous, loyal, charming, funny, empathetic—a latecomer to social democracy but with an early interest in social justice, an intellectual with a passion for art, nature and ideas, a man capable of deep friendships, with the energy and determination to exploit every advantage made possible by his great fortune. He wants to have an impact on the future and he has the means to do it. Over his relatively long lifetime, he will be an essayist, a book publisher, a magazine editor, a diplomat, a negotiator, a military officer, a pacifist, an art collector, a politician, a biographer, a librettist, a playwright, a poet, a foreign policy advisor, a lecturer, an art critic, a curator, a philanthropist, and a patron of the arts. He may sound like a hyphenate dilettante, but his effective and tireless devotion to every new project adds weight to his reputation—whether it’s preserving Nietzsche’s legacy or launching the city of Weimar’s third renaissance as a center of modernism, or negotiating a possible alliance between Germany and the Bolshevik government, or securing the safe passage home of more than 100,000 German soldiers from Poland after the war, or publishing the most beautiful edition of Hamlet, or co-writing the libretto of Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier—or simply bringing great minds and artists together as catalyst for many fruitful collaborations.

The further one travels along his timeline, the more Kessler surprises. Beyond the witty barbs, he is actually kind, generous to a fault, open-minded, adventurous, loyal, charming, funny, empathetic—a latecomer to social democracy but with an early interest in social justice, an intellectual with a passion for art, nature and ideas, a man capable of deep friendships, with the energy and determination to exploit every advantage made possible by his great fortune. He wants to have an impact on the future and he has the means to do it. Over his relatively long lifetime, he will be an essayist, a book publisher, a magazine editor, a diplomat, a negotiator, a military officer, a pacifist, an art collector, a politician, a biographer, a librettist, a playwright, a poet, a foreign policy advisor, a lecturer, an art critic, a curator, a philanthropist, and a patron of the arts. He may sound like a hyphenate dilettante, but his effective and tireless devotion to every new project adds weight to his reputation—whether it’s preserving Nietzsche’s legacy or launching the city of Weimar’s third renaissance as a center of modernism, or negotiating a possible alliance between Germany and the Bolshevik government, or securing the safe passage home of more than 100,000 German soldiers from Poland after the war, or publishing the most beautiful edition of Hamlet, or co-writing the libretto of Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier—or simply bringing great minds and artists together as catalyst for many fruitful collaborations.

Berlin. November 15, 1905

“I thought about the influence I have in Germany. . . No one else in Germany enjoys such a strong position, reaching into so many corners. To exploit this in the service of a renewal of German culture: mirage or possibility? Certainly someone with such means could be a princeps juventutis. Is it worth the trouble?”

***

Until Kessler, I had never understood why people keep diaries. The way I saw it, the amazing things that occurred to one over a lifetime could be rerun from memory—together with sound and images—like a well-archived YouTube channel. Why should one have to double down on thoughts and experiences by repeating them in writing—wasting precious time that could be spent out gathering more experiences to remember and think about?

Unless the intention was for others to read about those experiences.

Reading someone’s diary is not the same as reading an autobiography or a memoir. Diaries are history at its most immediate—raw data directly from the source. Even if a diary has been published and read by millions, a certain reluctance to trespass may linger in the mind of the reader. At any diary’s end—in death or its abandonment—a conduit to the inner thoughts of the diarist suddenly closes, and the reader is left bereft. The last entry of Anne Frank’s diary may be its most devastating, as we weep for what won’t be there as well as for what was.

What is a diary? Is it an external memory storage device, a warehouse for secrets, a receptacle for grudges and complaints, a cheap shrink? For those who have kept diaries it is probably some or all of those things. Even the verb ‘keep’ as in ‘keep a diary’ suggests secrets held safe and close—simply kept, rather than carelessly released into Instagram space.

In my youth, ‘diary’ evoked pages bound in tacky fake leather with a flimsy lock promising inaccessibility to prying eyes—what girls from 6 to 16 were given to record their every pink feeling. One was supposed to address the thing as Dear Diary, an audience of one awaiting tiny thoughts. But the layout—seven days to a page in the diary I was given—did not invite elaboration: The only entry worth remembering out of the handful I ever wrote involved an anachronism before I even knew the word: “Rode my pony to school.”

Post adolescence, in the analog universe, diary might give way to journal, implying entries with more gravitas—possibly even thoughts on infinity. Fake-leather was replaced by bookish cloth bindings, in keeping with deeper ruminations awaiting their journey from brain to pen.

And now there are the Julia-Cameron-coined ‘morning pages’, which encourage people to fill three pages daily with handwritten sentences–-to what end, is not entirely clear. Cameron believes that all people are creative, and by that she seems to mean that anyone can fill three pages a day with handwriting.

Whatever compels people to transcribe the quotidian moments in their lives rather than simply commit them to memory (whose job it is to hold on to events that matter), an industry has arisen from the urge to perpetuate the self on paper, launching a tsunami of selfie journalism across all media, online and off.

No one writes autobiographies anymore. We live in the age of the memoir—both the me and the moi in memoir nesting side by side within a quasi-literary format borrowed from the French. The popularity of the memoir means that classes in memoir-writing are sprouting up all over, like mushrooms after a summer rain. One such seminar was even hustled to an elderly Vassar class as a means of helping one to immortalize oneself for the grandkids. Sorry, but those kids, if they existed, would have better things to read than Oma’s output.

One doesn’t even have to be old anymore to write a memoir. Some memoir writers are so young, it’s only a matter of time before a ten-year-old pens My years as a kindergarten dropout.

Since the start of the internet, letting it all hang out has become so routine that even serious newspapers like the New York Times, the Guardian or the Washington Post reserve considerable amounts of space for intimate personal confessions or advice columns in which no subject is tabu and no bodily function or fluid eludes scrutiny. Social media has made tell-all the fuel that drives Facebook and Instagram, Tik Tok and YouTube, the content that sells newspapers, books, and magazines. The private sphere shrinks day by day as the public thirsts for more intimate content to amuse itself. One could argue that today’s collective voyeurism is better than beholding a beheading in 1789 (better viral than violent). But the bloodlust is there, driving the need-to-know crowd to seek out ever more revelatory details. There’s good reason for famous people to write their memoirs, as a way to control the narrative of their lives before some biographer (or their own child) dissembles it.

Memoirs are written to be read by others. Some diaries are, too, but many are not. Virginia Woolf asked her husband to burn her diaries after her death. He didn’t. The difficult decision to publish C.G. Jung’s legendary Red Book was based on a single entry in which he addresses imagined readers—which seemed to finally satisfy his heirs that he meant for it to be published.

Of the millions who have answered the call of the ego, few have written anything with the reach and ambition of the Kessler diaries. With all the postwar me-generations that have come and gone, no diarist has created a lasting work for our times comparable even to what Samuel Pepys or John Evelyn did four centuries ago—with the possible exception of Holocaust literature, a genre that could be dubbed a collective memoir of genocide.

The problem may lie in the ebb and flow of our friendships and the remoteness of our social encounters, especially in the Zoom era. Or it may be the all-important me now ascendent over us or they or you or even it. These days, diaries and memoirs rummage through private travails and triumphs in the attic of the self, with little regard for the world at large, let alone any other inhabitants of that world. Diaries and memoirs are becoming as hermetic as fiction—real-life fabrications of the ego. We’ve become a society of individual bubbles which collide occasionally, forcing us to look away from our screens for a moment before moving on.

Our era may be too indeterminate, too globalized to be pinned down by the words of any one diarist. It’s hard to imagine a living person today with the intellectual chops of a Kessler who could, at the same time, slip into any social situation as easily and as consequentially as he did. Even without his diary, Kessler is a one-off, a rare breed of humanist.

***

Kessler was a devotee of Pepys and Evelyn, (“I am very fond of these old diaries. Knowing old memories is like having a friend in a distant country.”) but his own diaries were reference material for a three-volume memoir he planned to write in the quiet twilight of his life. That twilight turned into a Götterdämmerung which obliterated his best intentions. He was only able to complete the first volume, which appeared in 1935. By the time he died in 1937, in exile and destitute, the diary was his only legacy.

The one volume of memoirs, Erinnerungen eines Europäers (Memories of a European) is a tantalizing appetizer from a different kind of writer, one who chooses his words carefully before releasing them along with events not found in the diaries. Gone is the savage wit, replaced by a heady nostalgia. We learn of his passionate La Bohème-ish love affair at 18 with Lisette, a French girl he rescued from a thug on the street. She eventually ends their hopeless union, marries another and dies giving birth, but not before sending Harry a farewell declaration of love. (It seems Kessler was bisexual after all.) It takes him a long time to get over Lisette: “It is the secret of love that man and woman can never completely understand each other and therefore the desire persists.”

We learn how reading Nietzsche empowered him to pursue a new form of pan-European diplomacy determined by culture rather than nationalism. Equally important was the influence of his Leipzig professor Wilhelm Wundt, the forgotten father of psychology, who moved psychology and consciousness away from religious or soul-oriented metaphysics and philosophy, placing them within the scientific parameters of biology and neurology.

I would gladly give Harry an extra ten years to finish those memoirs. But what is missing from this first volume is the edgy spontaneity of the diaries, their casual prose which was more accessible, more entertaining: Exquisite tossed-off lines that could be pointed or poignant, exciting on-the-spot reportages and analyses, intriguing hints at private sorrow, lyrical outbursts of awe and joy in the presence of beauty, nature or great art.

“The beauty of a thing lies much more in our imagination than in the thing itself.” That might be debatable, but Kessler placed great value on the power of the imagination in all aesthetic encounters, especially music.

He does have a few things to answer for: the occasional antisemitic aside despite his many close Jewish friends. As he grew older, however, he actively called out the antisemitism of others, and was prescient enough in 1925 to warn that German culture would not exist without the Jews.

All his efforts against the Nazis, whom he branded ‘these brainless, malevolent creatures’, would come to nothing:

Saturday, April 1, 1933

“The abominable Jewish boycott has begun. This criminal piece of lunacy has destroyed everything that during the past fourteen years had been achieved to restore faith in, and respect for, Germany.”

This was not the only time he voiced despair. At age 19, Kessler questioned his whole endeavor with this dark epiphany:

“I often think what a fool I am for keeping this Diary: what is it but a heap of rubbish, the result of lifetime and yet dead and senseless: the exact image of a man’s corpse. Whom does it interest? Me? I hardly ever read it. My heirs? Ten to one the minute I have closed my eyes and they have got my body out of the house they will sell it to some pork-butcher to wrap saussages in.”

That ‘heap of rubbish’ is now online for all to read.

***

Selected Links and bibliography

A biography of Count Harry Kessler: The Red Count by Laird M. Easton

The Diaries in English (selected entries)

Journey to the Abyss 1880-1918

Biography of Walther Rathenau, His life and work by Count Harry Kessler

Notes on Mexico by Count Harry Kessler

Germany and Europe by Count Harry Kesser Lectures delivered at the Institute of Politics, Williamstown, Massachusetts 1923

Erinnerungen eines Europäers von Harry Graf Kessler

The first and only volume of his memoirs

The man who knew everyone documentary in German (4×15 minutes)

The Harry Graf Kessler Society

Alex Ross on Count Harry Kessler

Alex Ross selection of Kessler on Music

Complete diaries of Harry Graf Kessler online at the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach