by Barry Goldman

This article is the second in a series. The first is here.

Justice delayed is justice denied. Everyone agrees. Lawsuits should be brought in a timely manner. If too much time goes by before a case is adjudicated, witnesses become unavailable, memories fade, evidence is lost, and it becomes harder to reconstruct events. Also, if there is no timeliness requirement, the threat of a lawsuit hangs over the parties indefinitely, and it prevents them from moving on with their lives. Therefore, many systems have a rule.

The Rule in place at the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), where I have arbitrated for many years, is 12206. It says this:

(a) Time Limitation on Submission of Claims

No claim shall be eligible for submission to arbitration under the Code where six years have elapsed from the occurrence or event giving rise to the claim.

So far so good. It’s a simple, clear, reasonable, bright line rule. Or so it appears. Let’s see how it works in practice.

Suppose the following: Old Mr. Murphy dies. Mrs. Murphy has never been involved in any decisions having to do with the family finances. She had her hands full managing the household and raising the kids. Now suddenly, without any background, training, education or experience, she finds herself responsible for a substantial sum of money. Though a friend of a friend she is introduced to Jones the Stockbroker.

Jones is an engaging young fellow, and he appears to Mrs. Murphy to be very knowledgeable with regard to stocks and bonds and mutual funds and variable annuities and real estate investment trusts and similar things. He is associated with a large and well-known brokerage firm.

Mrs. Murphy explains her situation, and young Jones appears to understand perfectly. He’s such a nice young man. Read more »

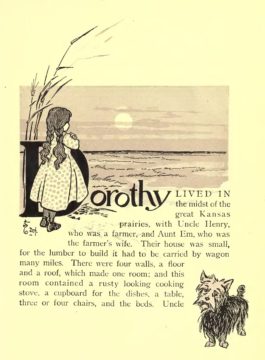

On a small paper bag maybe from a bookstore, one side Romeo’s soliloquy, “But soft! What light from yonder window breaks?” On the other side, these words: “Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cook stove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three of four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar–except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap-door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder

On a small paper bag maybe from a bookstore, one side Romeo’s soliloquy, “But soft! What light from yonder window breaks?” On the other side, these words: “Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cook stove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three of four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar–except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap-door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder I’ve recently started playing pickup basketball again. When I was younger, I played basketball all the time. At two or three years old, we had a toy hoop with a bright orange rim, white backboard, blue pole, and black base. It was, I believe, a “Little Tikes” brand hoop; I’ve just looked it up online, and my research seems to confirm this. In any case, I will now remember it this way—the vague memory I hold has solidified into one canonical version. But it might have been a different brand, the base of the hoop might have been a different color.

I’ve recently started playing pickup basketball again. When I was younger, I played basketball all the time. At two or three years old, we had a toy hoop with a bright orange rim, white backboard, blue pole, and black base. It was, I believe, a “Little Tikes” brand hoop; I’ve just looked it up online, and my research seems to confirm this. In any case, I will now remember it this way—the vague memory I hold has solidified into one canonical version. But it might have been a different brand, the base of the hoop might have been a different color.

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month.

I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Which is a wildly non-specific thing to say, since the province of Ontario, though only the second largest of Canada’s constituent divisions, boasts a surface area greater than those of Germany and Ukraine combined. But while I would normally designate as my destination the city in Ontario in which I mean to stay during my annual visit to my home and native land—as for instance Toronto, the provincial capital, where I went to high school and university; or Kingston, once Canada’s Scottish-Gothic capital, where my brother has settled with his family—the particular reason for this year’s sojourn, which began with a brief visit to relatives in Montreal, was my niece’s wedding, on August 12, celebrated at her fiancé’s family home in Frankford, with guests put up in the towns surrounding that hamlet on the River Trent, in Hastings County, the second largest of Ontario’s 22 “upper-tier” administrative divisions. Which all feels to me quite uncannily foreign, not to say unutterably vague. Hence simply: I’ve been visiting Ontario this month. Sughra Raza. Untitled, July 2020.

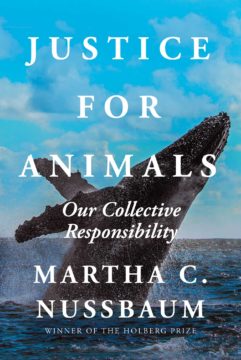

Sughra Raza. Untitled, July 2020. The cover of Martha Nussbaum’s Justice for Animals (2023) shows a humpback whale breaching: a magnificent sight, intended to evoke both respect for the animal’s dignity, and interest in its particular forms of behavior. Here is a creature which has moral standing, without being a direct mirror of our human selves.

The cover of Martha Nussbaum’s Justice for Animals (2023) shows a humpback whale breaching: a magnificent sight, intended to evoke both respect for the animal’s dignity, and interest in its particular forms of behavior. Here is a creature which has moral standing, without being a direct mirror of our human selves.

Resmaa Menakem’s

Resmaa Menakem’s  Dear Peridot Child,

Dear Peridot Child,