by David Kordahl

This column is ultimately a review of A Guess at the Riddle: Essays on the Physical Underpinnings of Quantum Mechanics, the short new book by David Z Albert, a philosopher at Columbia University and (as I found out last week) the graduate advisor of the founding editor of 3QuarksDaily, S. Abbas Raza. Unlike Raza, I have never met Albert, but my parasocial relationship with his work is midway through its second decade, which I am now acknowledging upfront.

I first became aware of David Z Albert when I was an undergraduate at a small Lutheran college in rural Iowa. On its top floor, the Wartburg College library had a large painting of Martin Luther, our hero, overseeing a bonfire of Catholic theology. But in the basement, where the unburnt books were held, I found a copy of Albert’s 1992 debut, Quantum Mechanics and Experience. The book’s style seemed wholly unusual to me. As a physics student, I wasn’t accustomed to books that were at once about science but somehow separate from it. I was impressed how Albert had retained only enough detail for a conceptual critique. I didn’t know, then, that its peculiar patois was just that of the analytic philosophers, with Albert merely adopting an eccentric dialect of that communal tongue.

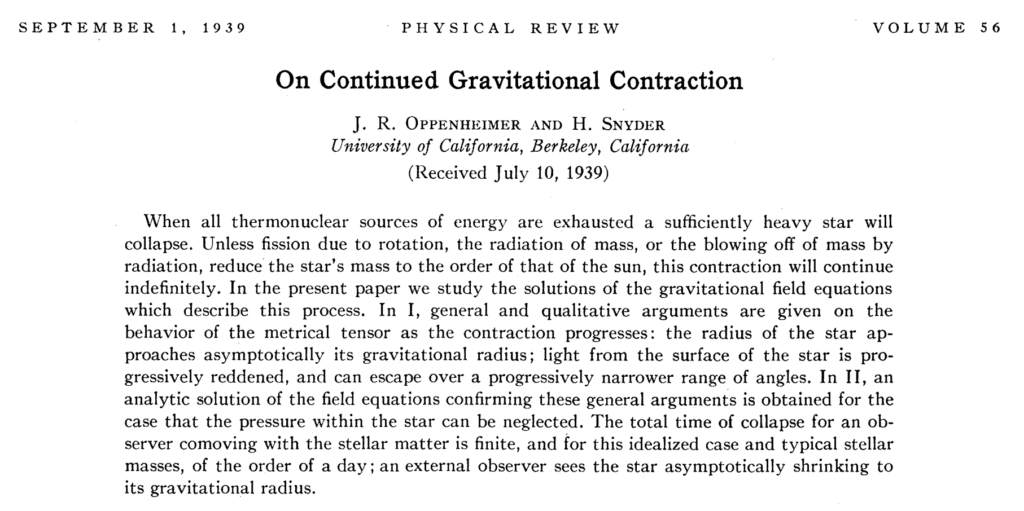

In my last column for 3QD, I wrote about how quantum models work. A physical system is associated with a quantum state. As time passes, the quantum state changes according to a deterministic rule, the Schrodinger equation, branching smoothly into distinct outcomes. At the end, you compare how much of the wave-function—what percentage of its total squared amplitude—is parked in each possible branch, and this gives you the probability of observing each outcome.

Quantum Mechanics and Experience is a book about the measurement problem in quantum mechanics, which (roughly) is the question of how nature decides which one of the predicted possibilities within the final quantum state we actually end up observing. Albert’s book wasn’t my first exposure these issues—I had read Nick Herbert’s 1987 book, Quantum Reality, a few years earlier—but it represented the first time I got the sense that these issues were still debated, and still up for grabs. Read more »

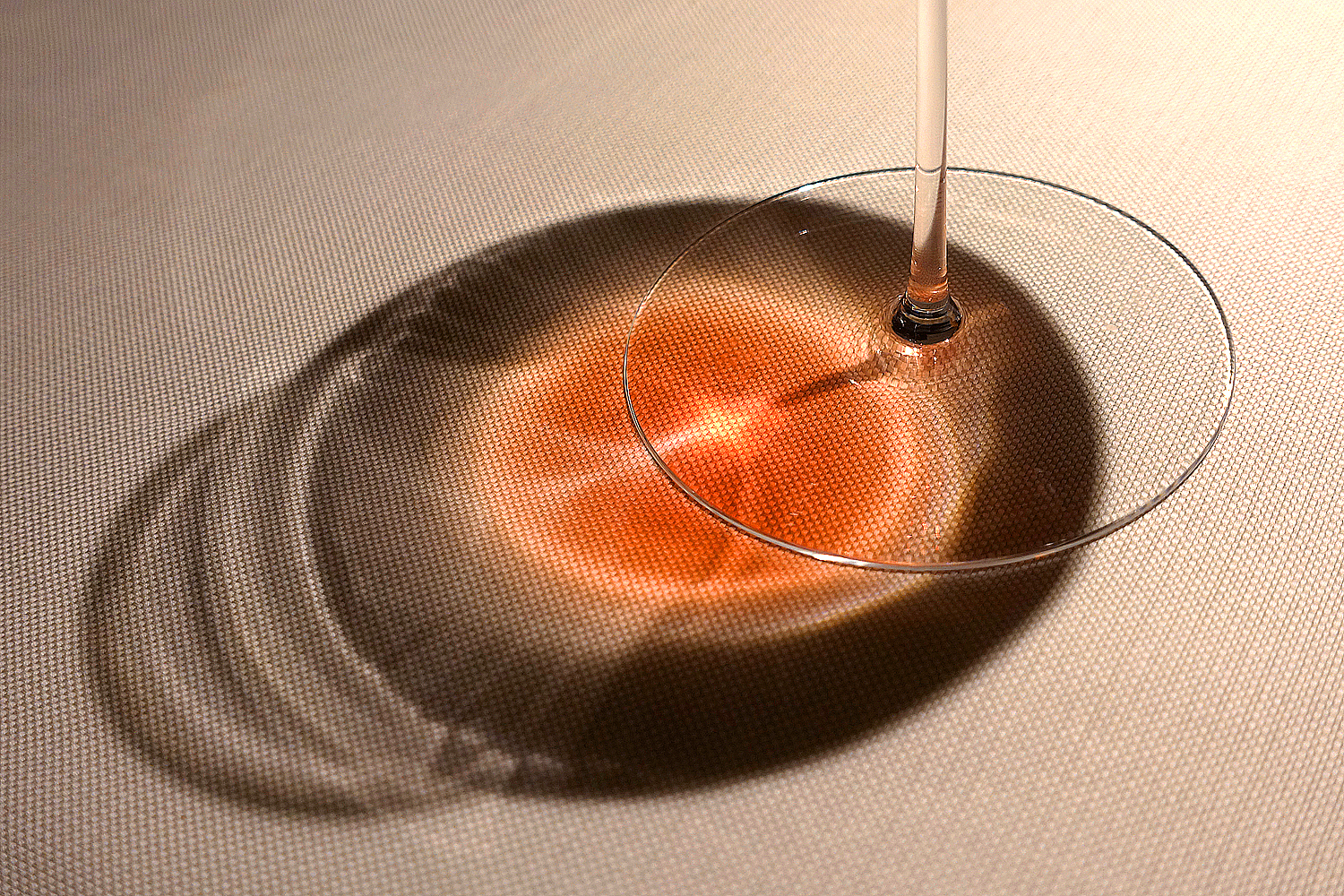

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics.

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics. Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work. ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say