Monday Poem

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by David Kordahl

The science lab and the theory suite

If you spend any time doing science, you might notice that some things change when you close the door to the lab and walk into the theory suite.

In the laboratory, surprising things happen, no doubt about it. Depending on the type of lab you’re working in, you might see liquid nitrogen boiling out from a container, solutions changing color only near their surfaces, or microorganisms unexpectedly mutating. But once roughly the same thing happens a few times in a row, the conventional scientific attitude is to suppose that you can make sense of these observations. Sure, you can still expect a few outliers that don’t follow the usual trends, but there’s nothing in the laboratory that forces one to take any strong metaphysical positions. The surprises, instead, are of the sort that might lead someone to ask, Can I see that again? What conditions would allow this surprise to reoccur?

Of course, the ideas discussed back in the theory suite are, in some indirect way, just codified responses to old observational surprises. But scientists—at least, young scientists—rarely think in such pragmatic terms. Most young scientists are cradle realists, and start out with the impression that there is quite a cozy relationship between the entities they invoke in the theory suite and the observations they make back in the lab. This can be quite confusing, since connecting theory to observation is rarely so straightforward as simply calculating from first principles.

The types of experiments I’ve had been able to observe most closely involve electron microscopes. For many cases where electron microscopes are involved, workers will use quantum models to describe the observations. I’ve written about quantum models a few times before, but I haven’t discussed much about how quantum physics models differ from their classical physics counterparts. Last summer, I worked out a simple, concrete example in detail, and this column will discuss the upshot of that, leaving out the details. If you’ve ever wondered, how exactly do quantum models work?—or even if you haven’t wondered, but are wondering now that I mention it—well, read on. Read more »

by Gus Mitchell

‘Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.’ Henry James apparently spoke these words to his nephew Billy James in 1902. TV personality Mr. Rogers later took it up – with an intriguing preface: ‘There are three ultimate ways to success: the first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.’

There is something revealing about that reformulation, from the beginning, to the second half of the twentieth century, that least ‘kind’ of all centuries. It holds true today as well. Kindness has become one of the indispensable buzz-virtues (or, as I conceive them, ‘word-virtues’) of our moment – see also ‘creativity’, ‘community’, ‘care’, and so on. The ubiquity of these words often masks a troubling lack of useful definition or resonance, not to mention the kind of morality-washing used to justify a great deal of lazy thinking and acting. Words in the place of a meaning. This trend has been helped on its way by an enthusiastically hijacking and hollowing by corporate or political instigators, whose interests are opposed to any genuine realisation of these ideals.

In a (no doubt vain) attempt to not be judged by some as callous or psychotic in this essay, let me preface everything to follow: the inherent qualities, the real virtues enshrined in words such as these, are ones I cherish. I’m not attempting to persuade anyone not to ‘be kind’, as you commonly understand it. Instead, I hope that by illuminating the fuzzy blubber gathering around these word-virtues – a blubber enshrined in the mimetic mindlessness of the internet – might help one see more clearly that, by them, we are selling ourselves short. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

The Lede: Wombats ate five children at a drive thru restaurant in Omegosh, Texas last week.

The Lede: Wombats ate five children at a drive thru restaurant in Omegosh, Texas last week.

The Body: A wisdom of wombats, on the run from massive fires in their Australian homelands, surrounded five children at a Checkers drive thru and lectured them on the disproportionate impact of the U.S. carbon footprint, before devouring them sans cutlery. Normally herbivores, the marsupials said later that they were eating young American child meat to make an ironic statement about climate change. Afterwards they were taken into custody and assigned a public defender. When reached for comment, their lawyer said the wombats were planning a hunger strike while in prison.

Ending: Does Jesus want us forgive the wombats, or blame the children? Perhaps we can do both.

*

The Lede: There’s someone in California who might like you.

The Body: California is home to nearly 40,000,000 people. One of them may like you. Like, really like you. That’s according to Cletus Nerdtoster, professor of probability statistics at California Polytechinc State University, who says chances are there’s someone in the Golden State who has the hots for you.

“Can’t rule it out. There’s just so many goddamned people here.”

But what to do about it? Nerdtoster has fewer insights into how to actually meet that person.

“I met my wife at the library. But if you’re not here in California, I guess that wouldn’t work.”

Nerdtoster says he is unfamiliar with how dating apps work.

Ending: Do you even want to be liked? Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

1.

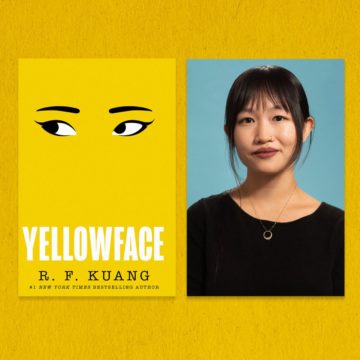

Does the title of the novel make you cringe or what?

In RF Kuang’s latest novel Yellowface, the setup is simple: within pages of the book’s opening, two frenemies –who met at an elite university–are having dinner together. Athena, who is Asian-American, has seen tremendous success in her work. The other woman June is white and has been anything but successful. Not surprisingly, June is envious of Athena’s career….Could it be because Athena is a drop-dead gorgeous person of color? Could it be because of her sexy British accent and tall ballerina-like figure?

Or maybe it’s because she is an incredible writer and knows what she’s doing?

June can only keep wondering…. Until, suddenly during Athena chokes on a pandan pancake and dies.

And yes, you guessed it: June steals Athena’s manuscript-in-progress… Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by R. Passov

Sometimes, you find yourself thinking about why something happened and get nowhere. For example, a year ago this October, my (ex)wife and daughter and I were visiting my son in his second year at a prestigious college where tuition exceeds the average income for a family of four. We had landed in St. Louis with the plan of stopping at a diner that my wife knew from an earlier drive out to Colorado. She and a friend had driven their dogs from our homes in suburban New York out to Telluride. They diner-hopped along the way and one stop was the Goody Goody Diner.

We arrived mid-morning on a Sunday and drove on wide, sparse streets – a seemingly random store or gas station surrounded by empty lots or abandon structures. After many turns and red lights we saw a small white brick building with an upside down neon sign.

After entering we found ourselves in a long line. Sunday brunch is popular. It didn’t take long to notice every diner on that morning was a person of color. I and my family are suburban white.

Maybe we showed concern, hopefully not that we were scared but rather that perhaps we’d stumbled into someone’s party. While silently working our contingencies, the couple in front turned our way. Ron, about 6’4”, built for business and his wife, Tanecia, also taller than me, were dressed in what looked to be their Sunday Church clothes.

Hi, Ron said, you guys visiting? Yes.

We exchanged pleasantries and I mumbled that we were visiting our son at the local, amazingly over-done college which happened to be smack in the middle of Ferguson. We felt so enormously self conscious to be visiting so soon after the riots. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

“Not altogether a fool,” said G., “but then he is a poet, which I take to be only one remove from a fool.”

“True,” said Dupin, after a long and thoughtful whiff from his meerschaum, “although I have been guilty of certain doggerel myself.”

—Edgar Allan Poe, “The Purloined Letter”

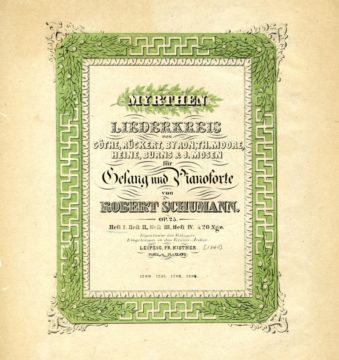

On the eve of their wedding day, on September 12, 1840, Robert Schumann presented Clara Wieck with a collection of 26 songs of his own composition, settings of poems by Goethe, Byron, Heine, Burns, and others. Arranged in four fascicles, the songs foreground literary works in which the speaking voice seems by turns male and female, at least by conventional codification. The poems’ themes range widely, including typical romantic topoi, such as flowers, the Scottish Highlands, and forbidden love affairs, but also drinking songs, ribaldry, and mock rhetorical argument. The very diversity of the selections suggests some definite, if eclectic and highly personal organizing principle had ordained them. And indeed, Schumann’s Myrthen opus 25, although named innocently enough for the myrtles traditionally carried by brides in the 19th century, was more than simply a Brautgeschenk or “bridal gift,” more than merely a pretty, arbitrarily assembled anthology (a term whose etymological roots are similarly floral), since it also celebrates the couple’s triumph over odds both familial and legal—Clara’s father had been resolutely opposed to the marriage, and she had had to win the right to marry Robert at court—as well as the union of two gifted and epochal musical artists.

Now, there is indeed a possible structural determinant of the selections for the cycle, one that tantalizingly suggests a secret code: for the number of its songs—twenty-six—is of course also the number of letters in the Roman alphabet; and musicologists have undertaken various ingenious attempts to discern an alphanumeric key or cypher in their distribution. Does the third song, for instance, “Der Nussbaum” (The Walnut Tree), in which a young woman dreams of a bridegroom, have some particular significance to the addressee, herself presumably about to see her own dream fulfilled, and whose name—Clara—begins with the third letter of the alphabet? Read more »

by Marie Snyder

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

I’ve encountered Maté in a few courses I’m taking, and have been strongly encouraged to watch his newest film and read his book several times now; I opted for the former. One follower was excited to tell me, with great confidence, that ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) is caused by a specific trauma and that everyone is carrying unresolved trauma which, if resolved, can heal physical ailments like cancer.

I’m dubious. I have some reservations that I’ve kept to myself until seeing so many in academia wholeheartedly promoting some poorly substantiated claims.

While Maté has some excellent techniques in the work he does, the way he presents and explains the material provokes me to look up research studies to try to corroborate many of his ideas.

I gobbled up his books twenty years ago, and there are some useful analogies and treatments in there, but even then there were parts that gave me pause. Read more »

When European colonists and used West African tribesmen and their descendants as slaves, they had no intention of learning anything from them or of adopting their ways. Their intention was simply to secure a source of cheap and tractable labor. But they were struck by the musicality of their slaves. And that musicality was to have a profound influence on their descendents and, in time, on peoples around the world. Let’s take a quick look at some moments in this centuries-long process of miscegenation, mutation, and cultural transmogrification.

Ecstatic Religion

Early in the seventeenth century, at about the same time Jamestown was being settled, Richard Jobson, an English sea captain, went to Africa and subsequently wrote that “no people on the earth [are] more naturally affected to the sound of musicke than these people.” A century and a half later, the Rev. Samuel Davies heard slaves in Virginia and remarked that the “Negroes above all the Human Species that I ever knew have an Ear for Musick, and a kind of extatic Delight in Psalmody.”

Published in 1640, The Bay Psalm Book was the first full-length book published in the English-speaking colonies, thus illustrating the importance that religious song had for the colonists. Singing schools—a 3 or 4 month series of meetings in which people learned to sing hymns—were held throughout the colonies. Meanwhile, as the slaves grew in number, they held festivals grounded in African custom, such as the ‘Lection Day festivals held in New England during which the slaves elected their own governors or kings, and the legendary Congo Square meetings in New Orleans. Read more »

by Bill Murray

In my exuberance after a spring trip to Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia, I proclaimed Africa the world’s greatest travel destination. It’s only fair to defend my thesis, for surely others will disagree.

First let’s dispense with the ‘Africa is not a country’ technicality by defining the travel to Africa that I have in mind as being, wherever the location, by some measure more raw, or relatively less mediated than a trip to most places in Europe or Asia.

What I have in mind for my ‘Africa’ is a place that affords a frontline opportunity for real experience of real life. Simple as that. In so much of Europe and much of Asia, what you’ve come to see and do is mediated by reservations, ticket punchers, tour guides, maîtres d’ and so on, putting the experiencer at some separation from the experience — the food in sought-after restaurants, the remnants of the Colosseum or Hadrian’s Wall or Stonehenge, cultural events like bullfights in Madrid, Japanese Sumo wrestling or the changing of various guards before various palaces from Beijing to Stockholm to the Kremlin. These are all surely there, but they are presented to you.

The simple elegance of Spanish tapas, the majesty of the Duomo, the magnificence of a Rodin in Paris, a van Gogh in Amsterdam or a David in Florence, come with a visitor’s expectations of a place because of its usually well-deserved reputation. The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in southern Uganda comes with no such burned-in reputation, and it will utterly amaze you. Read more »

by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

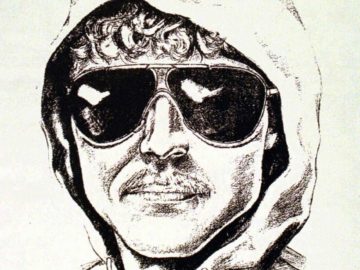

From the late 1960s to the mid 1980s, America was beset by a haunting array of serial killers: the Zodiac Killer, the Son of Sam, John Wayne Gacy, Ted Bundy, and the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, who just recently died in prison. For two dark decades, serial killers stalked the country, eroding our collective sense of safety and casting disturbed shadows over a world that made less and less sense every day.

In the 1990s, serial killers started to give way to mass shooters, who have terrorized Americans with increasing frequency for the past 30 years. Today, instead of protracted investigations that take years to find their targets (and in some cases never do), we have rotating 24-hour news cycles full of AR 15-wielding villains. Killers who used to operate for years, murdering victims in methodical patterns, have been replaced by death-cultists who kill the same number of people (or more) in one bloody event.

Serial killers defy easy understanding. In their horrific acts, they embody human immorality and insanity, but by eluding the authorities for months or even years, they demonstrate patience and discipline. They seem to be both malevolent and (in some ways) civilized.

Somewhere deep inside, we all want to believe that serial killers are impossible. Anyone smart enough to evade capture, write a manifesto, or plan elaborate rituals shouldn’t also be able to commit gruesome, inhuman acts. They remind us that our understanding of humanity is incomplete (at best) and perhaps quite flawed. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

I try to keep callbacks to a minimum in my columns here, but this one seems worth it. Be warned, though. It’s well into the weeds we go.

Last month, right here, I posted this piece.

“Are Counterfeit People the Most Dangerous Artifacts in Human History?”

It was a counter to Daniel Dennett’s recent piece in The Atlantic, “The Problem with Counterfeit People.”

As I wrote later in an email to Dennett, “I really only wanted to make two points in the article. (1) I worry that framing the issue as being about ‘counterfeit’ people deflects from the fact that, in my humble opinion, all the real harms [you cite] don’t require anything like ‘real’ AI – and they are mostly already here. (2) Probably, I am wrong (a lot of people seem to think so), but I also thought it was a weird way for you to frame the issue as I thought the intentional stance didn’t leave as much room as more conventional thinking about the mind for there to be a real/fake distinction.”

Much to my surprise our illustrious Webmaster S. Abbas Raza, who is a friend of Dennett’s, passed the piece along to him.

Dennett initially responded by forwarding a few links. I thought, surely, that is worth sharing. So, here they are.

“Two models of AI oversight – and how things could go deeply wrong” by Gary Marcus.

(Marcus features in my previous piece “Artificial General What?”)

He also sent this https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/08/tech/ai-image-detection/index.html, and this

“Language Evolution and Direct vs Indirect Symbol Grounding,” by Steven Harnad.

Later Dennett wrote, “The main point I should have made in response to your piece…is that LLMs aren’t persons, lacking higher order desires (see ‘conditions of personhood’) and hence are dangerous. There is no reason to trust them for instance but few will be able to resist. They are high tech memes that can evolve independently of any human control.”

I thought it would be fun to have my friend and colleague Farhan Lakhany, who is something of an expert on Dennett’s work and philosophy of mind in general, take an objective look at the exchange. Lakhany just successfully defended his Ph.D, Representing Qualia: An Epistemic Path out of the Hard Problem at the University of Iowa so I thought it would be great to have him agree with me that I am right. He did not. Here’s what he said. Read more »

She’s dead, he said.

So’s he, said she.

Kicked the bucket, he said.

Bought the farm, said she.

Under the clover, he said.

Crossed over, said she.

Iced with a heater, he said.

Sleeps with the fishes, said she.

Taken for a little ride, he said.

Gone to the other side, said she.

Flat-lined, he said.

Out of mind, said she.

To a better place, he said?

By heaven’s grace, said she.

Under the sod, he said.

To be with God, said she.

To Paradise? he said.

Would be nice, said she.

Could it be? he said.

Could it not? said she.

Jim Culleny; © 7/14/2007

by Joseph Carter Milholland

Lately, I have been thinking about the failures behind my most recent relationships: what led to the breakup but really what caused them not to begin at all. I have been wondering why I am always left with the feeling that the contact between the two of us never became more than surface level, and often not even that. As I wrestle with this sad fact, I have, as a form of fantasy and consolation, been thinking again and again of a scenario in which another person could know the real me.

In my imagined scenario, another person would shadow me for 24 hours – at least 24 hours, in my wilder imaginings maybe as much as a week. They would not interact with me, except for perhaps the occasional commentary or clarification as to what I was doing. They would see when I woke up, what and how I ate, how I worked, what I did with my spare time, the way I would take naps for 11 minutes and 35 seconds in the late afternoon, how I would take long walks in the evening listening to music, how I would make dinner while listening to a podcast or Youtube video, and then eat it while watching a documentary or disposable television show, how I would, during my workday, constantly refresh my podcast app and Youtube subscription to see if anything new had popped up, how I would also check the news in certain conflict zones to see if there had been an escalation, how I would read a poem each morning as soon as I woke up and often right before bed, how I would sometimes read a poem during breaks while at work but not as much as I wanted to, how I would have absolutely no set time as to when I ate, sometimes not eating anything until 5 or 6 or later, other times eating so much granola in the morning that the protein overlead would make the idea of eating unthinkable for 12 hours or more, how when I do my laundry, I take my pants out of the dryer ten minutes into a hot cycle and then hang them up semi-damp to remove the wrinkles without needing to iron them, how I make endless lists – lists of music I want to listen to, authors I want to read, books others have recommended, poems and short stories I recommend to others – and yet I am seemingly incapable of scheduling my day. They would see the sum of me, the sum of my most prized habits which I refrain from showing to anyone outside myself, the parts of me I admire or detest or am indifferent or resigned to but which are somehow opaque to others.

There is something narcissistic about this fantasy, but more significantly, it’s completely unrealistic. An observer necessarily changes the behavior of the person who is observed. If I was being watched during all my waking hours, I would fundamentally not be the same person I am when I am alone. Most importantly of all, who would consent to such a strange ritual? Read more »

by Jerry Cayford

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.

Wait! Before you insist the idea of Boomers shut out of power is ridiculous, that Boomers run the world, that at most the effect would be trivial and the concern petty, let me tell you another story, one whose outlines are well known. My father came out of graduate school in 1963 into the best seller’s market academics have ever seen. The Baby Boomers were just starting to hit college age, and universities were scrambling to hire enough professors to meet this huge wave of incoming students. He waltzed into a tenure-track position at a good university in one of the most desirable cities in the world. A few years later, he got tenure, despite publishing only one paper, not even as lead author (an unthinkable feat in the publish-or-perish jungle I encountered some decades later). He stayed there the rest of his career.

Now, it is no disrespect to my wonderful father, who is smart, a terrific teacher, and a valuable asset to his university, to acknowledge that his career started at an opportune time. Contrast his experience with my sister and her husband’s, smack in the middle of the Boomer generation. The year her husband came out of grad school, there were six openings in his field in the whole country. Universities now faced shrinking enrollment as the Baby Boomers passed college age, but were stuffed with tenured faculty still in their thirties and forties. My brother-in-law got one of those six positions—a one-year, non-tenure-track post—saw the writing on the wall, and used that year to apply to the Foreign Service and a viable career. Read more »

by David Greer

The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) and the southern resident orca (Orcinus orca) are dramatically different animals that employ curiously similar predation techniques, and both face extinction thanks in large part to their choice of prey.

The northern spotted owl, one of three subspecies of spotted owls, is slightly smaller than a raven and inhabits mature forests along the Pacific coast of North America from southwestern British Columbia to northern California. The southern resident orca, sometimes called the killer whale, occupies the same part of the world and is found primarily in the coastal waters of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, and most especially throughout the Salish Sea.

Though the extinction threats they face are different in nature, there is one very similar root cause—the fact that they are both fussy eaters.

The diet of the spotted owl consists primarily of two small rodents: bushy-tailed wood rats (otherwise known as pack rats) and flying squirrels. Like most other owls, the spotted owl hunts primarily in the dark. To catch its prey efficiently with minimal expenditure of energy, it has evolved two remarkable and complementary aptitudes: exquisite hearing and silent flight. Unlike some owl species that prowl at night in search of prey, the spotted owl simply perches in a tree, waits motionless, and intently listens. If it hears the scratching of pack rat toenails on a log or the soft impact of a flying squirrel landing on a tree trunk, it unfolds its wings and launches towards the sound. Like other owls, the spotted owl has evolved a structure and texture of feathers that ensures an almost soundless flight. Read more »