Reflection of two statues and a cell phone tower in a pool on the roof deck of the Tower Garden restaurant in Vahrn, South Tyrol.

Category: Monday Magazine

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Amazing New Technology Will Render all Computers Obsolete by Next Wednesday Lunchtime

by Richard Farr

From our Men’s Modern Living correspondent:

I know, I know. You’re thinking: “Don’t even start. I saw two dozen spittle-flecked jeremiads on this topic last week alone, including that 17,000-word essay by Randomdude in one of those illustrated monthly magazines they have at my club. Substack? It was called something like Apocalypse Now: Why You Should Be Running Around Shrieking With Your Hands In The Air. To be honest, I was forced to abandon it after a few paragraphs when I started to have painful attacks of ennui, déjà vu, and prèt-à-manger.”

No shame there! In this brave new world of moving fast and breaking the bleeding edge off things, not every writer can be hypnotically persuasive, even when the very fate of Mankind is at stake. But you need to pay attention now, because what the world’s most august technical gentlebros are saying about these latest developments is NOT HYSTERIA.

On the contrary, the new “automated calculating engines” are going to change everything, either in ways that we can’t possibly predict, but should be terrified out of our wits by, or else in ways we can predict and already have predicted in excruciating detail, and should be terrified out of our wits by. I mean it, and I’m not exaggerating: when these machines go mainstream, ka-poufff. Literally. In less time that it takes for you to say to your housekeeper “Alexa, order me three of them and then send two back because what was I thinking?” the whole world will have become unrecognizable, the way toast does when you put mashed avocado on top. Read more »

Monday, September 18, 2023

Atoms Of Truth: On Facts And Their Alternatives

by Jochen Szangolies

Sunil Rao, one half of the leading duo of the novel Prophet by Helen Macdonald and Sin Blanché, has a gift: he can tell trick from truth. Any fake is immediately obvious to him; any false statement revealed as such upon hearing it. Much more than a human lie detector, his abilities are not dependent on whether those making the statements—or indeed, anybody—know the truth: indeed, on occasion, he engages in accidental self-discovery, by uttering statements about himself and finding them true.

Rao, then, seems ideally suited to his secret service work, but, without giving away too much, things are more complicated than that. Nevertheless, somebody with his ability might seem to be an asset to have in your corner, in this age where simple truth seems under attack from multiple sides. Who wouldn’t want to read the news and just know what’s what? Know whether the latest fad diet delivers on its promise (although I’d venture a semi-educated guess there)? Perhaps even have a shot at the Big Questions™—God, life, the universe, and all that?

Indeed, to a scientist, philosopher, or any such habitual question-asker, perhaps nothing ought to seem more tantalizing than a direct mainline to truth. Mathematical physicist Geoffrey Dixon shows his literary sensibility when he begins his monograph Division Algebras: Octonions, Quaternions, Complex Numbers and the Algebraic Design of Physics with a series of brief ‘Screeds’ concerning a visitation by the Screen of Ultimate Truth, ready and waiting to spill the universe’s (mathematical, presumably) guts upon being prompted.

But what question to pose? Suppose you ask, as the physicist in Dixon’s Screed does, for the ultimate reason for the universe’s existence, only to be met with pages upon pages of incomprehensible symbols: what good is truth you don’t have the proper context for? Read more »

High Holy Devilry

by Barbara Fischkin

As the Jewish New Year 5784 unfolds, the late newspaperman Jimmy Breslin comes to mind. Jimmy was a great guy, an awful guy, and a Catholic guy. Channeling him now might be tantamount to sacrilege. Or, maybe not. My immediate ancestors, whose memory I honor this week, loved sacrilege. I imagine their beloved ghosts hovering over me in my unruly but spiritual garden of wildflowers and reminding me that they read Jimmy religiously, pun intended.

Fortunately, none of these relatives, many of them targets of anti-Semitism, were alive when Breslin was briefly suspended from his newspaper for unleashing a barrage of Asian slurs. Yes, that was the awful Jimmy. He apologized. During his long writing life he also published a trove of stories railing against injustice. Included among these were his December lists of “people I am not talking to next year,” a journalistic winter wind. A bit childish but also fun and laden with messages. Embedded in these lists were cris de coer against inhumanity, selfishness—and snobbery. Jimmy Breslin had no patience for elitism and, in one offering, depicted his ejection from the elegant 21 Club for, it seems, the mere crime of looking like a schlump.

In the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, Jews are asked to apologize to those they wronged during the past year. This week, like Breslin, I will also apologize. But first—and also in Breslinesque mode—I present a list of people to whom I will not be speaking this Jewish new year. I wish I could present this as original, but it has been done before—including by a reporter for the Jerusalem Post. We writers like to copy one another and a select number of us love to copy Jimmy, in particular. Read more »

Monday Poem

Celtic Knot

maybe you think I do not know

maybe you think I could not be

surely I’m not where I go

surely I am here with thee

but maybe moon is nothing old

maybe sun is never new

perhaps all stories have been one

maybe there’s no such thing as through

could be everything is here

could be everything is near

could be heaven is not far

could be now, just where we are

perhaps all maybes will be done

maybe all should-bes might be too

could be everything is one

within the shadow of we two

by Jim Culleny

3/24/12

Just for Fun

by Rebecca Baumgartner

“So why are you learning German?” I don’t remember who first asked me this, but over the following two weeks, it was a question I’d answer about 60 times.

And each time, I struggled to come up with a satisfying answer – and not just because of the limits of my intermediate-straining-towards-upper-intermediate German skills. The people around me, of various ages and life stages, had a variety of reasons for learning this language. Some had jobs in Germany or Switzerland and, although they mostly used English to get their work done, they felt excluded from casual conversations with their coworkers. Some had moved to a German-speaking country when their spouse found a job, and wanted to more fully participate in the culture they found themselves in.

Aside from a few people using the freedom of retirement and an empty nest to refresh a skill they’d last practiced during the Cold War, there weren’t many people studying German for the sake of studying German. When asked about my reasons, I usually said something along the lines of it being a hobby or something I was doing “just for fun” (a phrase that genuinely perplexed some people, usually after a 3-hour block of grammar lessons – “You think German is fun?”).

But the word “hobby” sounds too trivial, and the idea of having fun doesn’t really fit either. Every time I tried to answer this question, I butted my head against the walls of how Americans conceive of leisure time and what it’s for. Why am I spending my free time doing effectively more work? Am I just a masochist? What am I getting out of this, and is it worth it? Are my reasons less “real” than someone who needs to learn German for their career? Am I just a dilettante? Read more »

Against the Internet Novel

by Derek Neal

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

“I looked at my phone and scrolled through Instagram. Why did I do this? A habit, a reflex. I put the phone back in my pocket and scanned my eyes over the playground, a tinge of panic running through me until I spotted Lucy, swinging from the monkey bars. I watched for a bit until I reached in my pocket again, opening the Bumble notification that had just appeared.”

Scenes like this may occur in any contemporary novel without necessarily meeting the definition of an “internet novel.” To pass the threshold, the internet or the smartphone must play a pivotal role in the story, acting not as just a background item or a plot device, but as something that actively structures the consciousness of the characters. The characters’ inner lives must be conditioned in some way by their frequent use of the internet—in particular, social media via their phones—and this must then deeply affect their actions. In these novels, the idea that “the internet is not real life” is not true; the characters have crossed the Rubicon, as it were, to live in a universe where the internet and social media have been fully integrated with every other part of existence. This type of book, however, may be at odds with the reasons we read novels in the first place. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Law Versus Justice III

by Barry Goldman

Psychologists tell us we are susceptible to the “just world fallacy.” We think the arc of history bends toward justice. We think people, ultimately, get what they deserve.

Historically, this belief led to the practice of trial by combat. God, you see, favors the just. Since that is so, we merely need to arrange a fight between the competing sides in a dispute, and God will reveal which side is right by seeing to it that the right side prevails. Trial by ordeal works on the same principle. Suppose two disputants appear with equally likely explanations for some state of affairs. Both accounts cannot be true. To resolve the question, the disputing parties can be, for example, required to grab a glowing hot iron bar and carry it for a specified distance. After a proscribed number of days, their resulting wounds can be examined and compared. The person whose burns appear less festering and septic will be the one who is favored by God and ipso facto the one whose account of the situation is true.

We don’t do it quite that way anymore. But the essence of the trial by ordeal and trial by combat is still with us. When we have disputes that we can’t resolve ourselves, we hire champions to go forth and do combat on our behalf. They do it in dark wool suits rather than suits of armor, but the principle is the same. Our faith in this arrangement is similar to our faith in capitalism. Just as the invisible hand of the market is believed to promote Prosperity, the adversarial system is believed to promote Justice. The two mechanisms are equally marvelous. Read more »

Monday Photo

Batman? Batcat? Catbat? Bacatat? Frederica Krüger lazing in the sun in our kitchen.

Answers to everything, according to God, according to Martyn Iles

by Paul Braterman

When people tell you what they are, believe them. In the 2021 Facebook posting attached below, still available [1], he tells us exactly what he is, and since, in May this year, Martyn Iles became Chief Ministry Officer at Answers in Genesis, the $28 million dollar a year concern that runs Kentucky’s Creation Museum and Ark Encounter and has its own private jet, we ought to pay attention. All the more so since the announcement just one month ago that he is now the designated successor to founder and CEO Ken Ham [2]. So here are his answers to the burning questions of our times, given in full to avoid the risk of quote mining, with my own commentary just in case there is any ambiguity about what is being said. And he saves the worst till last, when he explains exactly how it comes about that people disagree with him, and how we should look on such disagreement.

The answer to gender identity – “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” [Gen 1:27]

I share Iles’ concerns about the use of extreme clinical procedures, but for the very opposite reason. I do not believe in rigid gender roles, and think that people should be free to live as they wish, subject to the rights of others, without the need for mastectomy or castration. Iles, on the contrary, thinks that gender roles are God-given and rigid (more on that below), and that for that very reason people should stick to the roles that they were born for.

The answer to sexual orientation – “And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man… Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh.” [Gen 2:22, 24]

It is difficult to know what to make of this. Read more »

Opera

by Nils Peterson

My First Opera

My first opera was at the old Met, Cav. and Pag, Cavalliera Rusticana and Pagliacci, cheapest seat in the house, last row, last seat, highest balcony in a corner, view of the opposite wing almost as large as my view of the stage which, in truth, was interesting – watching the preening before performing. At the intermission, I offered my seat to an older woman who was standing behind. As she thanked me, I could almost hear her thinking what a nice young man, but in truth, the tiny raked seat did not work with my six foot six frame and its basketball wrecked knees. I had been in agony, and her taking my seat and my standing was a blessing.

My Last Opera

As you get older you find there are things you just cannot do anymore. I have peripheral neuropathy. I was diagnosed with it when I was 65. It’s now almost a quarter of a century later. My diminishment was slow. First I had to give up tennis, then golf. Finally, a few years ago, of all things, the opera. So here are some thoughts on that.

On Sunday I went to my last performance at the SF Opera. I’ve had a half season ticket there for more than 40 years and I’ve had the best cheap seat in the house ever since the restoration of the opera house after the earthquake. Right side of the right aisle in the wheelchair row. Room for my legs and a clear sight of the stage. My last opera was Carmen, a very different Carmen from the one I first saw, or the one I saw in LA with a somewhat over-aged Placido as the Jose (this wretched machine doesn’t want to accept Domingo’s first name. it keeps wanting to turn him into Placid). This production had Don Jose and Micaela taking selfies, and simulated oral sex. Both leads were really fine, though Carmen’s voice may have been just a little small, but just right in timbre. The staging was very physical, and she was very good. She had a slim athlete’s body and exuded sexuality. Pastias was a Mercedes driven on stage out of which a drunken outdoor picnic evolved. (I think I even smelled exhaust, though I can’t believe it was really driven on stage. They must have pushed it in some way.)

However, I left at the intermission to drive home towards San Jose. I just had sat enough, the drive up, the lunch, the first two acts, and the coming drive home, and my right leg was beginning to ache and swell a bit. And as I went over it in my mind, I didn’t want to see Micaela come to a ruined, jealous Don Jose, nor did I want to see him kill Carmen in the last act, though I would have liked to have seen the street scenes which I’ve sung when my chorale did opera choruses. Read more »

Monday, September 11, 2023

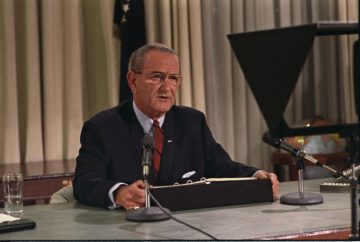

Darkness At The End Of The Tunnel: 1968 And The Destruction Of LBJ’S Presidency.

by Michael Liss

Some Presidencies just come apart: The men occupying the office are objectively unable to manage the chaos around them. Herbert Hoover’s might be thought of as in this category. James Buchanan’s as well. Perhaps Jimmy Carter’s. Others, like Richard Nixon’s, die of self-harm, unmourned. Still others end in “fatigue”—their party, or the public, essentially tires of them. Harry Truman’s flirtation with running for a second full term fell victim to Estes Kefauver, Adlai Stevenson, and a mostly uninterested Democratic Establishment. George Herbert Walker Bush found “Message: I care” not quite as compelling as he had hoped. Sometimes the public, or just the Party, wants a change.

What separates the survivors, the people who seek and succeed both at the job itself and the politics of getting reelected? It’s certainly not being free of the seven deadly sins. Nor is it being above politics. It’s a core philosophical anomaly of our system that our Chief Executive is charged with acting on behalf of all citizens while being the political leader of half. That takes, along with the talent, intelligence, and temperament to get the job done, a certain moral agility, a selective application of standards of right and wrong, sometimes even to the extent of muting the dictates of conscience. Presidents are in the business of making choices, often ones where there are shades of grey rather than clear bright lines, and, to make these choices, they have to call upon their own resources, both light and dark.

If you could somehow take samples of DNA from every President, good, bad and indifferent, and run them through a centrifuge, you might, might come up with a sample that resembles Lyndon Baines Johnson. A complex, contradictory man with a complex and contradictory record. Read more »

Dick

by Jonathan Kalb

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Gilman’s signal teaching talent was showing others how to read their own writing well, which he called an “indispensable skill.” His and Kauffmann’s “Crit Workshops” at the Yale School of Drama—required every semester for three years—were tiny, intensive seminars devoted to upping our games. We crit students venerated these men because we wanted what they had: perches at the increasingly rare prestigious intellectual weeklies (such as The Nation and The New Republic) that were surviving the withering assaults of the media age in the 1980s. Each three-hour Crit session focused on a single student paper. Dick (as he introduced himself) never bothered with written comments. In his classes, he’d read the paper aloud in its entirety, leaning back in his plastic chair, chain-smoking cigarillos, and channel the writer’s voice with his own inflections, like a Brechtian actor supplementing a role with his savvy persona. Thus he performed the model intellectual, articulating, in a stream of unsparing interruptions and digressions, the manner and temper of the “generally intelligent mind” we were told we should write for.

This was a thrilling and terrifying experience. Dick would stop to remark on any formulation, image, or thought that bothered him, not only flagging our dangling participles, flaccid metaphors, and baggy digressions but also speculating on the reasons for them. He’d ask tetchily about our intentions and then, with biting humor, pronounce Olympian verdicts on our evasions, confusions, pretentions, and oceanic ignorance. This painful, merciless crucible was everything I’d hoped for from that storied school. Read more »

There

From David Winner’s first column about his poignant relationship with buildings and their ornamentation, to Angela Starita’s discussion of the Bengali/Italian/Uzbek gardens of Kensington, Brooklyn as well her own growing up with her Italian-born father who became a farmer in middle-age, our column centers around place and what it signifies: architecturally, historically, emotionally. We will try to interrogate buildings: factories, apartments, houses, cities. Sometimes we will enter inside their doors to focus on what goes on inside.

by David Winner

When Angela and I visited Paris for the first time in the early nineties, we stayed in a large house near the Parc Monceau owned by a friend of my great-aunt’s, Henri Louis de la Grange, Mahler scholar and bona fide baron. When Alain, a former lover of Henri Louis, had us to dinner one night, he complained about a recent visit to Cincinnati. Echoing Gertrude Stein’s famous “no there there,” comment, he dismissed the city as “provincial.” When I repeated the comment to Henri Louis later over dinner with my great-aunt, he disdained Alain, from Normandy, as provincial himself.

That memory begs two questions. What constitutes provincial, and where and what is “there?”

Many students at the community college where I teach come from former colonies of the Spanish empire. Provincial backwaters to some: think poor Zama in Antonio de Benedetto’s eponymous novel, stuck in murky Asuncion, desperate to get transferred to Buenos Aires. My students often refer to the capital city of their country not by its name – Santo Domingo, Quito, San Salvador – but simply as “the capital.” After moving to Jersey City within spitting distance of Manhattan, those cities remain capitals for them, the antitheses of provincial.

*

I visited Riga, the capital of Latvia, which spent much of its recent history as a backwater of the Russian then Soviet empires, in the summer of 1997 when Angela was doing a program for journalists in Finland. I took the ferry across the Baltic Sea to Estonia, then a bus to Riga. The Soviet Union had only recently fallen, and it felt like a distant, exotic destination. Except it wasn’t. The well-preserved Old Town with its late seventeenth century German architecture bustled with tourist life. Read more »

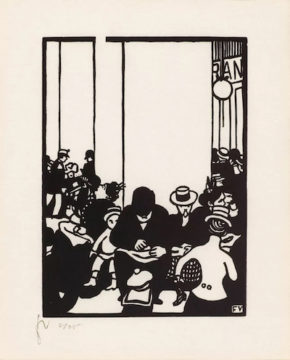

Monday Poem

The Man Who Shredded the Newspaper

by Anton Cebalo

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

This characterization is not mine but taken from Austrian writer Karl Kraus. Kraus believed this environment had to be held responsible for plunging Europe into war. He parodied its excesses in his 1918 play The Last Days of Mankind where he developed his signature montage style. In a time of upheaval, Kraus cut through the noise by repeating its own voice back at it, splicing quotes together into a new interpretation. As he recounted in the play’s preface, “the most improbable deeds reported here actually took place. The most implausible conversations… were spoken verbatim.” Kraus pursued a unique kind of literary realism with the perceptive eye of a documentarian, and in his crosshairs was the newspaper.

Like many writers and artists of the early 20th century—whose perspectives ring so familiar to us today—Kraus sought to dramatize how mass media, particularly the newspaper, was distorting the urban individual’s sense of place. Is it so surprising that writers and artists then, argues critic Lucy Sante, “took such pleasure in shredding it”? After all, the stakes were dire.

I have been reading Sante’s translation of one such “shredder”: Félix Fénéon. He is an individual who remained largely unknown during his life, but played an outsized role in modernism and early 20th-century literature. Fénéon found himself close to the heart of this media whirlwind I am describing, writing anonymously for the French newspaper Le Matin in 1906. But rather than get caught up in its bluster, he instead opted for an approach that was unique in its candor, simplicity, and intended speed of consumption. Read more »

Robert Frost’s Ghost: The Bread Loaf Writers Conference

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I walked through woods muddy and wet, feet sinking down into the boggy earth. With each step, mosquitoes rose up in clouds. It felt more like I was forging a river than walking a path through woods.

I was told that it was less than two miles to Robert Frost’s writing cabin in the woods. According to the Bread Crumb, the daily newsletter put out by the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, it was a must-see. Just follow the pink ribbons…it instructed. And sure enough, pretty pink ribbons were tied to tree branches, marking the way, whenever two roads diverged through the woods.

I had only applied to the conference on a whim. Well, not a whim exactly, but more like a major disappointment and a bad experience with a literary agent sent me spiraling… but then after a week of tears, I decided to just get back up again. What else could I do anyway? “Fall down seven times, get back up eight” 七転び八起き says the old Japanese proverb.

And so, I applied to several workshops and one residency.

I don’t recall where or how I first heard about Bread Loaf. Maybe it was from that old Simpson’s episode, when Lisa launches tavern-owner Moe’s literary career by sending his poem to a magazine:

Howling at a concrete moon,

My soul smells like a dead pigeon after three weeks.

I shut my window and go to sleep.

In my dream I eat corn with my eyes.

Moe’s poem creates a literary splash, and he is immediately invited to attend Word Loaf, where Jonathan Franzen and Michael Chabon—both played by themselves—end up getting into a fight. And, everyone but Lisa goes on a hay ride.

Thinking about it, though, I wonder if I didn’t first hear about Bread Loaf in connection to the great American poet Robert Frost.

Do American kids in public schools still memorize his poems? Read more »

Join My Cult

by Scared Ignoramus Fellowship Leader Akim Reinhardt

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.

Actually, that last bit’s the key: don’t believe in anything.

Do you believe in anything? If so, stop.

My Church of Sacred Ignorance implores followers to embrace their dunderheadedness. You don’t know shit. Neither do I. Let’s stop pretending.

Yes, we all know some basic facts. Sun go up, sun go down. Ice is cold, fire is hot. Chocolate makes you happy (unless you’re one of those people). But the rest of it? Mostly make believe. And it’s time to face up to it. Let us come together in our dumbness and sit quietly beneath the stars, waiting for big cats to eat us. Through such acts of honesty and modesty will we find salvation . . . which doesn’t actually exist, but maybe we’ll trick ourselves.

But I don’t wanna be pushy. I understand that choosing to join a cult is a Big Decision. You probably have some questions. It’d be weird if you didn’t, even if we accept that you won’t understand the answers, and that the questions themselves are largely random, inadequate expressions of anxiety and confusion. Nonetheless, I’ve prepared the following FAQ to help ease your towards your destiny.

How much will this cost?

There are many ways to answer that question, most of them Socratic. For example, once you stop believing in money, what will you do with yours? Will you give it all away? Will you destroy it? Will you smother it in gravy and eat it? Will you hand it out to those poor schlubs who still believe in it? Will you gather it up in a big pile and stare at it, wondering why you ever cared?

Does truth have a cost?

Or I could just say $49.95 + tax if that sounds better. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. At Totem Farm, April 2021.

Digital photograph.