by Muneeza Shamsie

This year, 26 January marks the fifth death anniversary, of Sahabzada M. Yaqub-Khan (1920-2016), my uncle. To me it seems as if it was yesterday. He was my mother’s youngest brother and her only sibling in Pakistan. The bond between them was so close that I cannot remember a time, when he was not integral to my family life. To my younger sister, Naushaba (now Naushaba Hasnain) and me, he was always ‘Mamou’. I have no idea when Mamou and I first met. He was a prisoner-of-war at the time I was born in Lahore. As I grew up I was told by my parents never to ask him about his POW years because it was such a dreadful experience. I learnt in time, that he had been captured in Egypt (at Bir Hachim after the Battle of Tobruk) and he escaped in Italy with two fellow officers – the future Commander in Chiefs of the Pakistan and Indian armies respectively, Generals Yahya Khan and Kumaramangalam – but they had been recaptured. Mamou was then moved to a concentration camp in Germany. He had utilized those years to learn languages: French, German, Italian and Russian. Afterwards he was sent to England to convalesce. There he was often mistaken for his second cousin, the Nawab of Pataudi, the famous cricketer. The resemblance was so uncanny that two generations later, my daughter Kamila chanced upon a photograph in a book on cricket history. She did a double take and thought ‘What is Yaqub Nana doing here?’

My first conscious memory of Mamou revolves around the unsolved mystery of Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten, my favourite book. This had big pictures of kitten in a lovely soft, velvety material. Possibly Mamou used to read it to me. One day the book disappeared. For some reason I thought that he was responsible. He would often tease me – and ask with a big grin – until I was quite grown up. “Who took Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten?” I would point to him. He would go into peals of laughter. And I still don’t know what happened to Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten. Read more »

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

I think it is fair to say that we usually see science and magic as opposed to one another. In science we make bold hypotheses, subject them to rigorous testing against experience, and tentatively accept whatever survives the testing as true – pending future revisions and challenges, of course. But in magic we just believe what we want to be true, and then we demonstrate irrational exuberance when our beliefs are borne out by experience, and in other cases we explain away the falsifications in one way or another. Science means letting what nature does shape what we believe, while magic means framing our interpretations of experience so that we can keep on believing what feels groovy.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

Let me recommend a New Year resolution, in case you don’t have one yet: Be nicer to people you disagree with.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

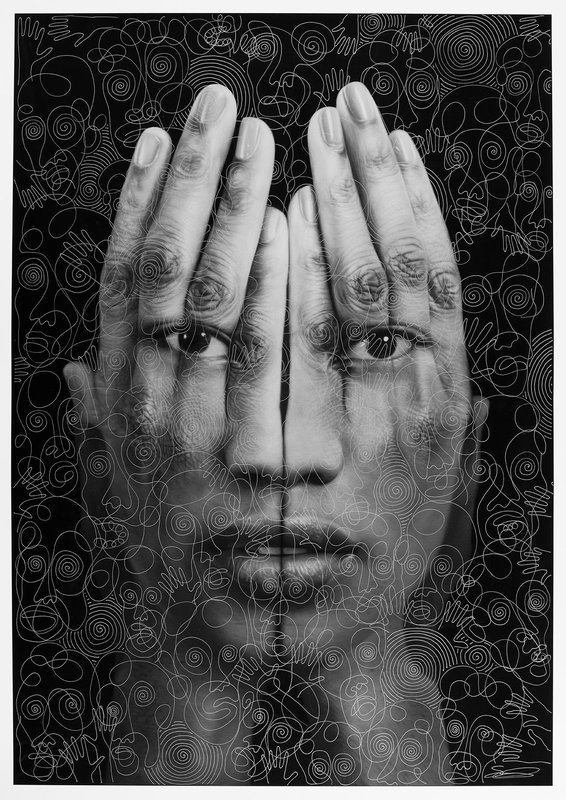

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.