by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Tim Sommers

A libertarian. Old joke. I mean, marijuana is not even illegal in a lot of states anymore. How about this one? A libertarian walks into a bear. Okay, that’s not really a joke. It’s the title of a recent book by Matthew Honogoltz-Hetling, subtitled “The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (And Some Bears)”. It’s about a group of libertarians who move to a rural town with the express purpose of dismantling the local government and producing a libertarian utopia. The resulting problems with coordinating refuse disposal attract a lot of bears and the lack of a government makes it difficult to mount a response. Bears 1. Libertarians 0.

I have been thinking about libertarianism again since I read Thomas Wells’ smart 3 Quarks Daily article Libertarianism is Bankrupt arguing that libertarianism, “like Marxism or Flat-Earthism”, has “nothing to offer”. Which is kind of unfair to Marxism if you ask me. But a real-world example of how dead the libertarian horse is, is offered by the departure of many recovering libertarians from the Cato Institute recently, the bulk of them forming a new non-libertarian think tank (Nikensas). What lead most of these former Cato staffers to abandon libertarianism was the existence of a political problem that they felt libertarianism had no response to. I bet you can guess what it is. (I’ll tell you at the end, just in case.)

In the meantime, given the moribund state of libertarianism, rather than beat on it some more, I thought it would be fun to return to its glory days, to Robert Nozick and his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Nozick was arguably the most philosophically sophisticated libertarian ever. He was charismatic. He was purportedly widely read in the Reagan White House. And he was lauded as one of the Philosopher Kings of Harvard by Esquire Magazine in 1983 (including a full-page photospread in which he looked very thoughtful). (The other Philosopher-King, John Rawls, refused to be interviewed or photographed for the piece.) Read more »

by Thomas Larson

One late spring day in my twelfth-grade English class, my teacher carried a box up and down the aisles, handing each of the thirty students a new Signet Classic paperback. Mr. Demorest, who had a waddle under his chin and a doo-wop singer’s curve in his hairdo, said this novel might be tough reading and pledged plenty of mimeos. He said the school district had prepared us by reading, in previous grades, Silas Marner, Lord of the Flies, A Separate Peace, and The Scarlet Letter, whose baroque language (“Fruits, milk, freshest butter, will make thy fleshy tabernacle youthful”) brought a cascade of snickers from the back of the room. Demorest said that he’d taught this novel before, but he’d be reading it with us again, since with literature there was always more to glean. That word glean fell inside me like a coin tossed in a fountain. The novel was Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles.

Demorest said to get through the first 50 pages until Tess meets Alec. What’s the story? It’s about a girl becoming a woman. As we’ll see, she has a child by one man, Alec, runs from him and marries another, name of Angel. Angel is her true love but, fearful he’ll discover her dark secret on his own, confesses the child’s fate to him. Mortified, Angel abandons her, and she ends up with the first man again, with whom she is forced, for the sake of her family and her reputation (what’s left of it) to—well, you’ll see, he said. Don’t get hung up on the names of English villages. You might look up any Biblical allusions. Pay close attention to how the book makes you feel. Does it make you feel? Where in the story are you moved? Make a mark. Do you care what happens to Tess? Why? Think about it—what does Alec and Angel want from Tess and what does she want from these two men, opposites though they may be? Read more »

by Varun Gauri

In his recent book A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders offers insights into writing good short stories. I may consider his craft advice in another context; here, I want to explore the book’s implications for bad stories and, specifically, the bad stories we call public narratives.

Saunders contends that “we might think of the story as a system for the transfer of energy.” This comes in a discussion of Chekhov’s “In the Cart,” in which a description of Marya, an unhappy, lonely school teacher, creates an expectation for the reader that Marya must necessarily endeavor to become less unhappy, less lonely, as the story unfolds. That’s the energy transfer — an observation at one point in time creates heightened attention, and specific expectations that are the springboard for action, later on.

Public narratives are similar. When we say America is “the land of free,” we not only evoke, implicitly or explicitly, the stories of the American Revolution and the liberation of people under the Axis powers, but create specific expectations that America will later fulfill or fail. Robert Shiller, in Narrative Economics, makes a similar point: “If we want to understand people’s actions . . . we need to study the “terms and images that energize” (Shiller is quoting the historian Ramsay MacMullen). Authoritarian societies provide many examples of the energetic function of public narratives; for example, a statement that the Aryans were the master race was not only an historical claim but an exhortation to make it true, by dominating and destroying other races. Read more »

by Filippo Santoni de Sio[1], along with Marianna Capasso, Rockwell F. Clancy, Matthew Dennis, Juan Manuel Durán, Georgy Ishmaev, Olya Kudina, Jonne Maas, Lavinia Marin, Giorgia Pozzi, Martin Sand, Jeroen van den Hoven, Herman Veluwenkamp[2]

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture. Read more »

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

I love birds, and I’m obsessed with words, so I suppose it stands to reason that I’m fascinated by the names of birds. I enjoy the “what it says, it does” names such as gnatcatcher and wagtail. (Further investigation reveals that the gnatcatcher family includes gnatwrens such as the chattering gnatwren and the trilling gnatwren, who I assume also do what their names say.) There are also bee-eaters and brushrunners, leaftossers and treecreepers, berrypeckers and foliage-gleaners.

Rollers perform acrobatic flight maneuvers to woo a mate or protect their territory. Bowerbirds build elaborately decorated structures to attract a mate, and some ovenbirds (furnariids) build nests of clay that roughly resemble tiny ovens. Weavers are known for their intricately constructed nests, which they build by weaving grasses and other types of vegetation.

I also delight in names that describe a bird’s appearance: the checker-throated stipple throat and the harlequin duck, for example. The male twelve-wired bird-of-paradise has twelve wiry filaments near his rear that he uses in his courtship display. The prothonotary warbler was named for a yellow-robed notary at the Byzantine court. The rainbow-bearded thornbill is a hummingbird with a narrow glittering band along its gorget (throat feathers) that ranges in color from green to red (more visible in the males than in the females). Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Friedman’s account starts with Adam Smith, the father of capitalism, whose “The Wealth of Nations” is one of the most important books in history. But the theme of the book really starts, as many such themes must, with The Fall. When Adam and Eve sinned, they were cast out from the Garden of Eden and they and their offspring were consigned to a life of hardship. As punishment for their deeds, all women were to deal with the pain of childbearing while all men were to deal with the pain of backbreaking manual labor – “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground”, God told Adam. Ever since Christianity took root in the Roman Empire and then in the rest of Europe, the Fall has been a defining lens through which Christians thought about their purpose in life and their fate in death. Read more »

by David M. Introcaso

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “Tackling the Climate Crisis” Executive Order signed January 27th failed to make any effort to address the increasingly dire health effects caused by the climate crisis. This may seem surprising since, for example, just one-month earlier Lancet published its fifth, well publicized and highly regarded annual report, “Countdown on Health and Climate Change.” The report’s introduction opens by asserting planetary warming is “resulting in profound, immediate and rapidly worsening health effects.” Nevertheless, the executive order makes no mention of the Medicare and Medicaid programs and ignores the fact the US health care industry’s greenhouse gas emissions significantly contribute to climate crisis-related health effects. This is disturbing since the federal government, responsible for safeguarding the health of America’s most vulnerable citizens, should not allow the healthcare industry to systematically harm their health.

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “Tackling the Climate Crisis” Executive Order signed January 27th failed to make any effort to address the increasingly dire health effects caused by the climate crisis. This may seem surprising since, for example, just one-month earlier Lancet published its fifth, well publicized and highly regarded annual report, “Countdown on Health and Climate Change.” The report’s introduction opens by asserting planetary warming is “resulting in profound, immediate and rapidly worsening health effects.” Nevertheless, the executive order makes no mention of the Medicare and Medicaid programs and ignores the fact the US health care industry’s greenhouse gas emissions significantly contribute to climate crisis-related health effects. This is disturbing since the federal government, responsible for safeguarding the health of America’s most vulnerable citizens, should not allow the healthcare industry to systematically harm their health.

We have known for decades that greenhouse gas emissions significantly contribute to the prevalence and exacerbation of numerous disease conditions. The Countdown report documents at length morbidity and mortality due to heat stress and heatstroke, wildfires, flood and drought and the transmission of numerous infectious vector-born, food-born and water-borne diseases including dengue, the incidence of which has grown thirtyfold over the past 50 years threatening half of the world’s population. The Biden administration is aware that during the past 20 years there has been a 54% increase in heat-related deaths among those over age 65 and that nearly half of Americans breathe unhealthy air that explains why fossil fuel use accounts for 58% of excess US deaths annually. The administration knows this because the Obama administration published in 2016 the nearly encyclopedic report, “The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States.” Read more »

by Thomas O’Dwyer

“Trust the science; follow the scientists” has become a familiar refrain during our past year of living dangerously. It is the admonition of world health organisations to shifty politicians; it is good advice for all whose lives have been battered into disruption by Covid-19. But another insidious pandemic has been creeping up on us. The World Health Organization calls it the “infodemic”. It includes those endlessly forwarded emails from ill-informed relatives, social media posts, and sensational videos full of spurious “cures” and malicious lies about the virus and the pandemic. The disinformation isn’t all the work of internet trolls, conspiracy theorists and “alternative” medicine peddlers. Some actual scientists have been caught in acts of deception. These are people who undermine whatever faith the public has left in science, and who sabotage the credibility of their scrupulous colleagues. One of the worst cases of fraud was Dr Andrew Wakefield’s bogus 1998 research paper linking vaccines to autism, which endangered the lives of countless children before it was debunked and its author struck off the UK medical register. In this 700th anniversary year of Dante Alighieri’s death, we should reserve a special place in his Inferno for those who profit from turning the truths of Mother Nature into dangerous lies.

“If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it,” the physicist Richard Feynman once said in a lecture on scientific method. It’s a noble truth — your theory is wrong if the experiments say so — but given the flaws of human nature, it’s not that simple. Sloppy work or deliberate fraud can make your theory seem correct enough to get published in one prestigious journal, and cited in many others. Scientific theories should follow the Darwinian principle of “survival of the fittest”. Yesterday’s cast-off ideas (goodbye, phlogiston) may pave the path to progress, but along the way, there are also some fake signposts pointing in wrong directions. Read more »

The Brothers Kathwari

after Iqbal

You know the secret

I lack depth

You have a home

I’m a wanderer

You control the sky

I’m prisoner of desire

You profit by interest earned

I’m losing the race

Your ships float in the air

My boat is without a sail

Restless, you’re spring

I’m fall

You’re weak. You’re strong

I’m this. I’m that. So?

***

Translation created from the original Urdu by Rafiq Kathwari who has a new collection of poems “My Mother’s Scribe” available here.

by Charlie Huenemann

“. . . . For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception. […] The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations. There is properly no simplicity in it at one time, nor identity in different; whatever natural propension we may have to imagine that simplicity and identity. The comparison of the theatre must not mislead us. They are the successive perceptions only, that constitute the mind; nor have we the most distant notion of the place, where these scenes are represented, or of the materials, of which it is compos’d.” (David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, 1.4.6)

So when Hume looked inward he found nothing stable: nothing but “a bundle or collection of different perceptions”, he said. But when he wrote about looking inward, he produced intricate and elegant successions of words like the paragraph above, which vividly describes that disordered jumble of perceptions and thoughts. One wonders how a mere bundle of perceptions could produce such a fine account. If Hume were correct about the nature of the mind — an ever-flowing chatter with no suggestion of unity — one might expect to read instead:

“…he kissed me in the eye of my glove and I had to take it off asking me questions is it permitted to enquire the shape of my bedroom so I let him keep it as if I forgot it to think of me when I saw him slip it into his pocket of course hes mad on the subject of drawers thats plain to be seen always skeezing at those brazenfaced things on the bicycles with their skirts blowing up to their navels even when Milly and I were out with him at the open air fete that one in the cream muslin standing right against the sun so he could see every atom she had on when he saw me from behind following in the rain I saw him before he saw me however standing at the corner of the Harolds cross road with a new raincoat on him with the muffler in the Zingari colours to show off his complexion and the brown hat looking slyboots as usual what was he doing there where hed no business…” [James Joyce, Ulysses] Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

New York Times op-ed columnist Charles Blow continues to make the rounds with his new book, The Devil You Know. In it he advocates for a reversal of the Great Migration, when Black Americans fled Jim Crow violence and sought economic opportunity in Northern and Western cities during the first half of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, these refugees from the American South were met with more of the same, Blow argues in several recent interviews. Still, most considered escaping the situation in the south a general improvement, a premise he agreed with until recently.

In Professor Hope Wabuke’s review on NPR, she notes how a speech Blow heard by entertainer and activist Harry Belafonte challenged his thinking about the Migration, prompting this book. Based on recent interviews Blow’s premise is that a new Black migration from the North back to the South will give Black Americans a greater share of political power in America, locally and nationally. Born in Louisiana, he’s recently returned to the south himself and currently resides in Atlanta. The recent political shifts here in Georgia bear him out. Atlanta has become an internationally celebrated Black city that’s been led by Black mayors since 1973. In the past decade or so, Stacey Abrams and many others worked to elect President Biden and Vice President Harris, as well as Senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, our first Black and Jewish senators respectively. People expressed shock that this could happen. But that’s only because they’ve not been paying attention to what’s been happening in places like Georgia.

I wish to echo Blow’s argument and highlight a necessary strategy for political change. Based on what Abrams and her allies have done here in Georgia—still unfinished work—there is no reason not to think about this in terms of transforming the entire south. I will argue that Blow’s argument has a lot of merit and is how political change happens. When thinking of history, people like to focus on extraordinary individuals and events, but the reality is that changing the politics of a place is a long hard slog undertaken by everyday men and women. Doing that work is going to be critical to creating an enduring and vibrant democracy. Building and transforming institutions are the key to long term change. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Fabio Tollon

It is becoming increasingly common to talk about technological systems in agential terms. We routinely hear about facial recognition algorithms that can identify individuals, large language models (such as GPT-3) that can produce text, and self-driving cars that can, well, drive. Recently, Forbes magazine even awarded GPT-3 “person” of the year for 2020. In this piece I’d like to take some time to reflect on GPT-3. Specifically, I’d like to push back against the narrative that GPT-3 somehow ushers in a new age of artificial intelligence.

GPT-3 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is a third-generation, autoregressive language model. It makes use of deep learning to produce human-like texts, such as sequences of words (or code, or other data) after being fed an initial “prompt” which it then aims to complete. The language model itself is trained on Microsoft’s Azure Supercomputer, uses 175 billion parameters (its predecessor used a mere 1.5 billion) and makes use of unlabeled datasets (such as Wikipedia). This training isn’t cheap, with a price tag of $12 million. Once trained, the system can be used in a wide array of contexts: from language translation, summarization, question answering, etc.

Most of you will recall the fanfare that surrounded The Guardians publication of an article that was written by GPT-3. Many people were astounded at the text that was produced, and indeed, this speaks to the remarkable effectiveness of this particular computational system (or perhaps it speaks more to our willingness to project understanding where there might be none, but more on this later). How GPT-3 produced this particular text is relatively simple. Basically, it takes in a query and then attempts to offer relevant answers using the massive amounts of data at its disposal to do so. How different this is, in kind, from what Google’s search engine does is debatable. In the case of Google, you wouldn’t think that it “understands” your searches. With GPT-3, however, people seemed to get the impression that it really did understand the queries, and that its answers, therefore, were a result of this supposed understanding. This of course lends far more credence to its responses, as it is natural to think that someone who understands a given topic is better placed to answer questions about that topic. To believe this in the case of GPT-3 is not just bad science fiction, it’s pure fantasy. Let me elaborate. Read more »

by Mike O’Brien

They say that everyone’s a critic. Some more than others. I have a particularly critical streak, that occasionally strays into full-on curmudgeonry. I have a few excuses. First, the generally awful and worsening state of the world tends to put me into a bit of cranky mood. Second, I am lazy, and picking at the flaws in other people’s work is easier than creating something new. And third, there is a lot of really awful, slap-dash work being done in the world of letters that cries out for detraction.

As a break, if not an antidote, to my nay-saying tendencies, I’m going to attempt something a little more constructive this time around. My first column, way back when, was basically a riff on all the facets of my generalized anxiety, and the ecological facet featured prominently there, but there’s still some unpacking left to do.

First, some predictions. After all, anxiety implies that I think something is going to happen, and in this case that something is very bad and very difficult to avoid. Mass extinction will continue, and continue to accelerate, for the rest of my life and beyond. Global warming, ocean acidification, habitat destruction and atmospheric carbonization will continue to blow past every “point of no return” that scientists set, and narrowly human-regarding effects will continue to immiserate billions of people. If we were the kinds of creatures, organized in the kinds of societies, that were capable to avoiding these inevitabilities, we would not be as far along the road to perdition as we are. This is not about what might happen. This is about what has happened and will continue to happen. Read more »

by Callum Watts

Growing up often feels like a process of finally understanding advice you completely ignored when it was first given to you. For me, this often has the form of thinking I’ve just discovered a profound insight about life, only to realise that it sounds entirely cliché once articulated. Perhaps it supports Plato’s idea that nothing brand new is every really learnt, because learning is really just remembering innate wisdom. More likely though, it’s just a happy reflection of the fact that there really are many general lessons to be learnt on how to live well. Happier still, these are shared and passed down not by philosophers, but by everyone, and so they become clichés. The past year of lockdowns has given me such a remembering, specifically, on the nature of how we find meaning.

Lockdown leaves us bereft of ordinary sources of meaning and value. This is extremely hard to do anything about because meaning is a little like happiness, the pursuit of it tends to scare it away. It is often the by-product of other activities, rather than the goal pursued. Like happiness, it also seems to be the case that the more our source of meaning rests on the dogged pursuit of a single thing, the more it is hostage to the what one thing, and so the more fragile it is.

For example, a person who mainly finds a sense of meaning through their work is extremely vulnerable to existential crises if their job fails to deliver that sense of purpose. The so-called midlife crisis is often (not always) a reaction to professional disappointment, a sense that one’s career has not really lived up to what was demanded of it. In this scenario the failure of a career to have delivered meaning can result in one’s whole existence appearing pointless all of a sudden. Read more »

by Joan Harvey

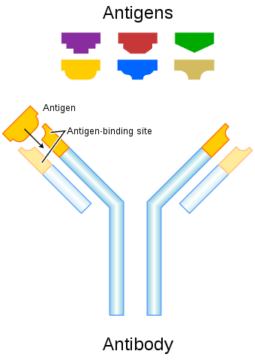

As we’ve all noticed, as soon you mention something about, say, your neighbor’s annoying poodle and your phone is anywhere within a three mile radius, you immediately get ads for poodles, poodle accessories, poodle food, and yet more poodles. I must have been talking or writing to someone about my immune issues, or possibly just Covid, and boom, they got me. Among all the ads I get for sheer underwear with snakes on it, there it was: immunology, Coursera, first week free, then $49 a month. Okay, I thought, I should know something about this, I’ll sign up, learn a bit, and go on my merry way. Little did I know. Because I’m someone who often doesn’t pay attention to details—exactly the wrong type for this sort of thing—I accidentally ended up in a course from Rice University designed for people with a serious interest and commitment to actually knowing how antibodies work.

I’m not much for video learning in general, or at least I hadn’t been until Covid, when a friend pointed out to me that the wonderful British-Israeli cookbook writer Yotam Ottolenghi did a Master Class. Up until that point I had conscientiously avoided Master Class and all those celebrities telling you they have the answer to life and if you just follow their advice you are guaranteed to become a confident-glamorous-successful novelist-filmmaker-model-architect. I’d also never had a cooking lesson, and found Ottolenghi’s cookbooks (of which I have four) intimidating, though when I attempted one of his recipes, or, more usually, part of one, it was always delicious. I would not have considered learning cooking from anyone else, but Ottolenghi was irresistible. So I paid the fee and there he was in my kitchen: relaxed, gay, handsome, with his wonderful accent, pouring olive oil on everything, squeezing lemons with his hands, squooshing garlic, talking me through each step, making everything easier. With him nearby I was no longer the anxious cook I often am; I was relaxed and reassured, and, following his steps, the food I turned out—Smacked Cucumber Salad with Sumac-Pickled Onions, Mafalda Pasta with Quick Shatta, Pea Spread with Smoky Marinated Feta—was actually amazing. I was only sorry there weren’t more recipes. But that was the extent of the video learning I’d done until my venture into B-cell arcana. Read more »