by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

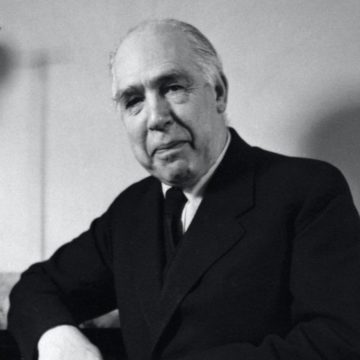

At MIT outside the Economics Department there was one scholar, whose several lectures I have attended was Noam Chomsky. I knew of him as a pioneer in modern linguistic theory, but his fame in the outside world is as America’s topmost dissenter (his position is somewhat like what used to be that of Bertrand Russell in Britain, a towering figure in his own subject philosophy, but his fame outside was that of Britain’s leading dissenter).

At MIT outside the Economics Department there was one scholar, whose several lectures I have attended was Noam Chomsky. I knew of him as a pioneer in modern linguistic theory, but his fame in the outside world is as America’s topmost dissenter (his position is somewhat like what used to be that of Bertrand Russell in Britain, a towering figure in his own subject philosophy, but his fame outside was that of Britain’s leading dissenter).

Chomsky in his lectures used to tirelessly blast the framework of American imperial policy, the capitalist military-industrial complex, the corporate-controlled media machinery for manufacturing consent, and the near-complete lack of control of common people over economic policy. I often agreed with the main thrust of his lectures, but the question that nagged me, but never could ask him in the surging crowd of his admirers around, was about the feasibility of the socio-political alternatives he might have in mind.

In some of his writings his constructive ideas seem close to old-style left-libertarian or anarcho-syndicalist views; in one place he describes his ideological position as revolving around “nourishing the libertarian and creative character of the human being”. What little I have read of this positive side of his ideological position has left me somewhat unconvinced; I have wondered if he has fully applied his mind to the various problems that arise in the real world beyond the anarchist or left-libertarian utopia. Read more »

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural.

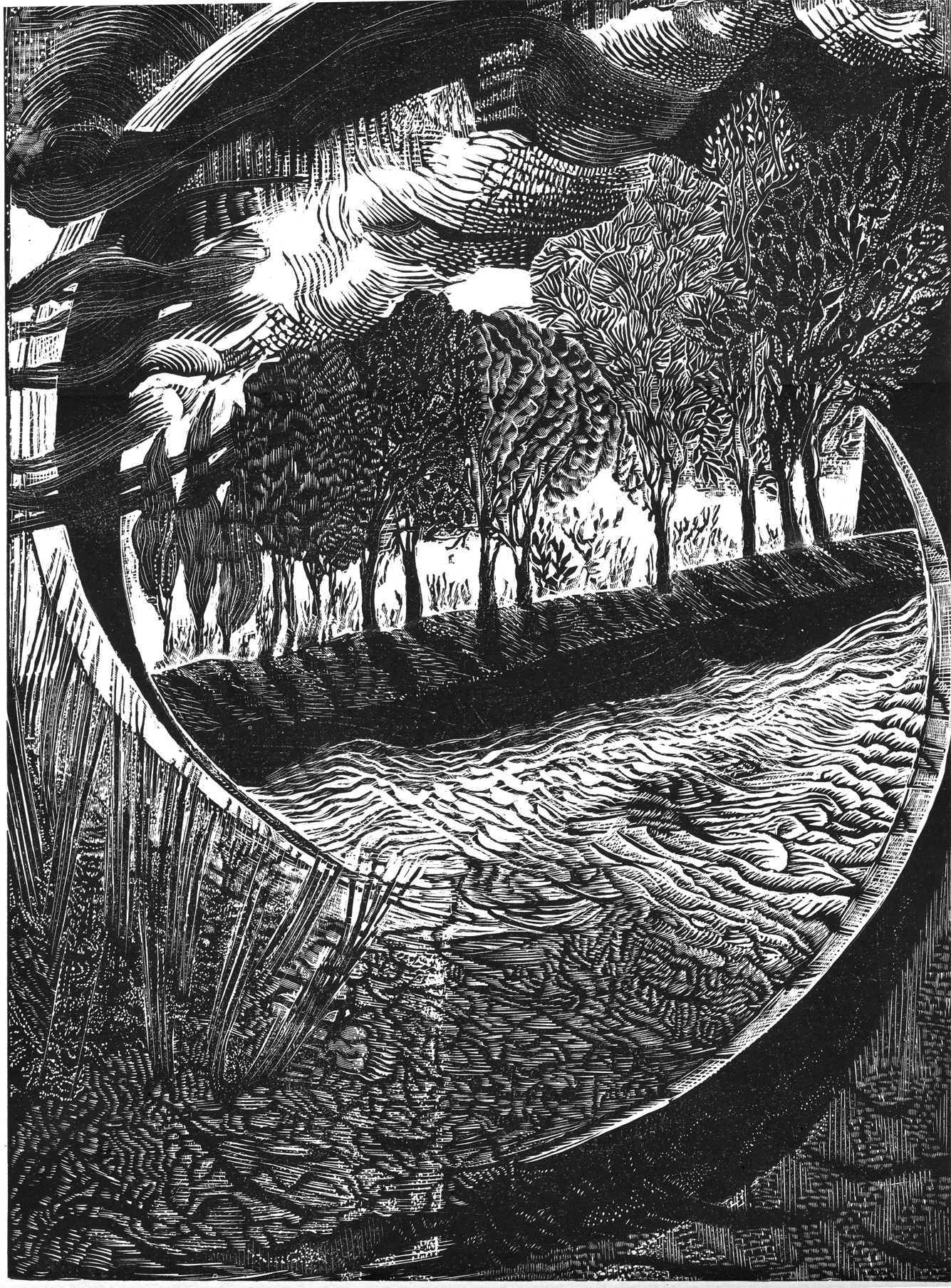

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural. Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

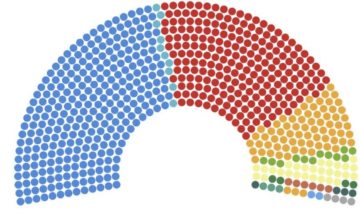

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?