by Mark Harvey

Mormons and Indians of the old west don’t have a nice history. In 1865, just as the Civil War ended, Ute Indians and Mormons began their own version of a seven-year war near Manti, Utah, over land, grass, cattle, and survival. It was called The Black Hawk War, named after a particularly capable Ute warrior. When the war finally ended, some 75 Mormons and several hundred Indians had been killed. The Indians put up a ferocious fight, but ultimately the Mormons prevailed and settled vast parts of Utah and Nevada.

So it’s not always easy to bring Mormons and Native Americans to the same side of a fight, but the city of Las Vegas managed to do so when it made an aggressive water grab on ranch lands and sacred grounds to its north a few years ago. With the explosive growth of the city, drought, and a limited water supply from the Colorado River, the town’s elders went looking for precious groundwater hundreds of miles to the north. What entailed was a thirty-year quest that involved big money, lots of lawyers, questionable science, wildlife biology, and sacred Indian grounds. When the Las Vegas water authority began that quest, little did they know they’d meet the wrath and fast war footing of Mormons and Indians. Ultimately the plan failed.

Las Vegas was once a tiny town in a vast desert where there lived but a few farmers and their families. The town wasn’t always short of water, primarily because at its beginning there were far fewer people and the valley where it sits had productive artesian wells. The very name, Las Vegas, means “The Meadows” in Spanish and was coined by a Spanish trading party in 1829 as it traveled to Los Angeles on the Old Spanish Trail. The party actually stopped there for water. Archeological evidence shows that Native Americans lived in the area beginning over ten thousand years ago.

The town really came into action during the 1930s when The Bureau of Reclamation built Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and created Lake Mead, the largest reservoir of fresh water in the United States. It was the vast man camps built around the dam’s construction and the consequent need for entertainment that first brought gambling, prostitution, drinking at Olympic levels, and steady entertainment to the town.

Since the dam’s construction, Las Vegas has grown extravagantly year after year. From the 1930s to the 2008 recession, the city’s population doubled almost every single decade. The lowest decadal growth rate it experienced in those years was sixty percent. Today the population of the Las Vegas metro area is close to 2.2 million people. You don’t need a doctorate in urban planning to predict that a city that large in a desert that, on average, only gets 4 inches of rain per year might someday have a water problem. In six of the 12 months, the valley usually gets less than one day of precipitation.

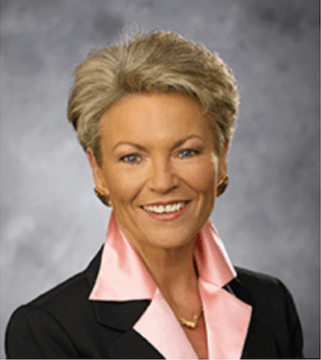

One person who saw into the dry future and did something about it was Pat Mulroy, who moved to Las Vegas at age 21 to study German literature at the University of Las Vegas Nevada. After partially completing doctoral studies at Stanford, a low paying administrative job in Clark County (the county seat of Las Vegas), and then a couple of promotions, Mulroy found herself at the age of 36, and with two small children at home, put in charge of the Las Vegas Valley Water District. (Mulroy offered to be interviewed for this article, but the timing didn’t work out.)

From that appointment, Mulroy spent the next 25 years in the sharp-elbowed and male-dominated world of water wars. She became legendary in Colorado River water politics, either admired for her energy and ambition or reviled for her efforts to take precious groundwater from ranchers far to the north of Vegas. In the style of a Robert Moses or Floyd Dominy (but all the while mothering two young children), Mulroy quickly organized six other neighboring water districts to form the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) in 1991. At its beginning, the SNWA was a small operation with a paltry $600,000 budget but through various sales taxes, Mulroy managed to turn the organization into a behemoth with tens of millions of dollars of revenue. In 2020, SNWA’s operating expense was $282 million and its assets were listed at $5.4 billion.

Realizing that Las Vegas’s main source of water, about 300,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water per year (stored in Lake Mead) could not sufficiently supply the still booming growth and the ambitions of the go-go developers and Casino owners, Mulroy and the SNWA began quietly buying up thousands of acres several hundred miles to the north, with plans to drill for groundwater and then pump it south in a massive project. In 2006 alone, the SNWA bought seven ranches.

The early estimates for the project were about $2 billion. But with a planned 460 miles of pipeline, 200 miles of powerlines, and four pumping stations, SNWA increased its cost estimates to nearly $8 billion, and closer to $15 billion including financing. The project would take decades to pay off and financing would continue well past the middle of this century.

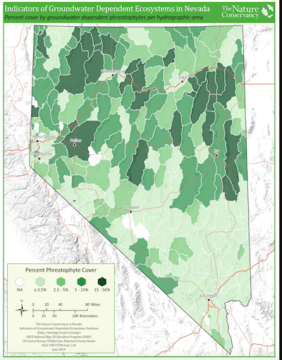

To understand Mulroy’s plans, you have to understand something of the geology and hydrography of the area. Las Vegas sits at the south-eastern edge of The Great Basin. The Great Basin is so named because under its vast parched lands there are great reservoirs of groundwater that never reach the sea. The Great Basin includes most of Nevada, almost half of Utah, a large part of Oregon, slivers of California, Idaho, Wyoming, and even the very northernmost part of Baja California. It’s a vast area defined by its hydrography and to use a hydrographer’s term, it’s an endorheic basin. Endorheic basins are closed bodies of water with no access to the sea or major rivers leading to the sea.

If you’ve ever visited the Great Basin, the concept of a sea or large body of water is hard to fathom. It’s a land with sparse vegetation and the vegetation that does live there has names like shadscale, saltbush, iodine bush, and greasewood–plants that are the botanical equivalent of tough guys.

But there is a vast quantity of groundwater deep under the surface in a series of complex, sometimes interlocking hydrographic units. In fact, there are trillions of gallons of water underground in the Great Basin. Nevada is divided into 232 individual hydrographic areas, each with its own specific characteristics of surface water and groundwater. The SNWA went after four of those units: Spring Valley, Cave Valley, Dry Lake Valley, and Delamar Valley. And while the SNWA had hundreds of millions of dollars to fight with, they wildly underestimated the commitment Mormons and Indians living in those valleys had toward protecting water that sustained both their survival and their spiritual beliefs.

Cleveland Ranch and The Church of Latter-day Saints

The Cleveland Ranch sits on the western side of Spring Valley between the Schnell Creek mountain range and the Snake range. It has a storied past but by far the most notorious character in its 150-year history was the man who built it, Abner Cleveland. By most accounts, Cleveland, who started the ranch in the 1870s and ran it until his death in 1903 was an extraordinary man who would offer to ride the toughest of his hundreds of horses when his hired hands refused to. Tough though he was, he also fed his own cats and prohibited the firing of guns around his house as he didn’t like scaring the wild birds. Said to be a soft-hearted man, he kept his favorite roan mare until she died at age 38.

Cleveland built the ranch up into several thousand acres and several thousand cattle. His first cattle were of Mexican breeds but by 1876 he began to import and breed Herefords. Shortly he was breeding some of the best bulls in the world and even imported one bull from Herefordshire, England, named Downtown Hero.

The ranch changed hands a few times over the 20th century and in 2000, The Mormon Church purchased it. The ranch runs a cow-calf cattle operation and uses most of its calves for humanitarian aid and to feed the needy. The Church has a massive system of canneries and food processing centers around the country, supplied by its many ranches and farms.

When The Church learned of SNWA’s plans to drill for groundwater in Spring Valley and realized the vast quantities of water to be piped to Las Vegas, they realized that their ranch was in jeopardy. As a livestock operation, they relied on both groundwater and surface water to grow hay and water their cattle. The Church figured if the project were built it would be the end of The Cleveland Ranch.

So they hired Paul Hejmanowksi, considered by many to be one of Nevada’s best litigation attorneys and included in lists such as Best Lawyers and Super Lawyers. Hejmanowski had done previous work for The Church and had a good working relationship. He was also well known for large settlement cases elsewhere in the country.

Hejmanowski quickly realized that the case was intensely complex and involved the intersection of hydrology, geology, and advanced computer modeling. He needed a world-class groundwater specialist and recruited Norm Jones, a highly respected civil engineer who specializes in groundwater and who is now the Department Chair of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Brigham Young University.

At issue was whether the massive pumping of groundwater to Las Vegas would dry up surface and groundwater rights held by Cleveland Ranch. For nearly 100 years, the state of Nevada has had a policy that prohibits “groundwater mining.” Groundwater mining, in essence, is defined by pumping out more water from an aquifer than is naturally replenished by snow, rain, and surface water. Groundwater mining can destroy natural springs and lower water tables thereby destroying wells used in the nearby region.

SNWA spent millions of dollars and tens of thousands of man-hours developing models to show that their project would not be mining groundwater but would be sustainable and would not adversely affect Cleveland Ranch, or the ecology and water tables in the other three valleys.

So in the summer of 2010, a few months before a scheduled hearing, it was left to Norm Jones and his team to challenge the science and engineering of the model. They only had about seven weeks to prepare and due to a legality, Jones was not allowed to build his own model but had to rely entirely on SNWA’s findings.

“Their report was a masterpiece of obfuscation,” Jones said. “They had these maps at the very end of the report and they were microscopic. And their timeline for analyzing the project was only 75 years. They used 75 years because that’s how long they predicted the original pumps would last. But you don’t build a $15 billion project and abandon it because your pumps wear out.”

One of the standards by which the Judge in the case made his decision on the project was whether the underground water table would be recharged naturally in a “reasonable amount of time.” Jones decided to really test the SNWA model over a ridiculously long time frame. Using his computers, he ran Las Vegas’s pumping scenarios and what the city predicted would be the natural recharge of the aquifer over a 2,000 year period. “We ran the scenario for 2,000 years and it still didn’t reach equilibrium,” Jones said. It also showed that to ever reach any sort of equilibrium in Spring Valley meant taking a lot of groundwater from neighboring valleys.”

According to Jones, when he cited SNWA’s own numbers and predictions on water drawdowns, the Las Vegas team balked. “They said, ‘You can’t trust our models, our drawdown models aren’t that accurate,’” Jones said.

The Tribes

The oldest known petroglyphs in North America are in Nevada’s Great Basin and date somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago. Several millennia before the Bellagio and before the Hoover Dam, various tribes lived in the Great Basin. There were the Freemont, the Moapa, the Shoshone, the Goshutes, the Paiutes, and dozens more. The Shoshone word for the tribes is Newe, meaning “The People.” The Newe people occupied large territories in the Great Basin, gathering plants and hunting wildlife with the change of the seasons.

About 10 miles south of the Cleveland Ranch as the crow flies, and still in the Spring Valley, there is a site as sacred to the Goshutes, Western Shoshone, and Paiute tribes as the Salt Lake Temple is to the Mormons. Known as The Swamp Cedars or Bahsahwahbee in the Shoshone language, the site is a grove of Rocky Mountain Juniper trees about four miles long and two miles wide. Rocky Mountain Junipers do not normally grow at such a low elevation—about 5,800 feet. They are a mountain tree more often seen several thousand feet higher. Rocky Mountain Junipers grow in 39 different mountain ranges but Spring Valley at Swamp Cedars is the only valley where they exist. The Rocky Mountain Junipers growing in Swamp Cedars are so unusual in their development and isolation that some biologists consider them to be on their way to becoming a new species with tolerances for very salty soils not usually seen in conifers. The junipers are sustained by springs emanating from the same aquifer relied upon by The Cleveland Ranch.

The Swamp Cedars have long been a place for the tribes to gather, make offerings to their creator, heal, and find refuge. According to Dr. Monte Sanford, an environmental consultant for the tribes (and who was instrumental in helping Swamp Cedars become a designated Traditional Cultural Property under the Park Service in 2017), it has long been a place for indigenous people from all over the Great Basin to gather, sometimes for weeks. It was a place for rain dances and circle dances and according to Sanford, the waters there are considered to have healing powers and medicinal properties.

But Swamp Cedars is also a place of great mourning for the Shoshone. It is the site of three Indian massacres, the first of which was even worse than Wounded Knee. In a public hearing in 2017 concerning the SNWA plan, Sanford said, “In 1859 the United States Army killed anywhere from 500 to 700 Indian people; children, men, woman, dogs. And that was the largest Indian massacre in the history of the United States.”

There were two subsequent massacres at Swamp Cedars, one in 1863 and the other in 1897, in which several hundred more Indians were killed. Thus the area holds tremendous significance for the tribes, both as a site of worship and healing and as a site of mourning ancestors.

When the tribes got word of Las Vegas’s plans to pump billions of gallons of water out of the Spring Valley aquifer, they believed the plan would kill the springs that sustained the Rocky Mountain Junipers and provided the healing waters they had come to cherish. They hired their own counsel, attorney Paul Echo Hawk, a registered member of the Pawnee Nation and resident of Pocatello, Idaho. Echo Hawk comes from a storied family. His father Larry Echo Hawk was Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs during the Obama Administration and his uncle, John Echo Hawk is director of the Native American Rights Fund and was listed as one of America’s 100 most influential lawyers by The National Law Journal.

The tribes didn’t have lavish amounts of money to spend on the trial and Echo Hawk was put on a tight budget. To save money he would live for weeks at a time in his truck camper while working in Carson City, where the trial and hearings took place. “There were dozens of witnesses, thousands of pages of documents and I was just one attorney,” Echo Hawk said. “The winter months were cramped and cold but there wasn’t much to do besides work on the case.”

When Echo Hawk began fighting against the SNWA project, he felt he was starting on poor footing because in 2006, in a stipulated agreement, the Federal Government had essentially endorsed SNWA’s plans without consulting the tribes. The agreement is signed by four federal agencies including the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which has a fiduciary responsibility to consult with tribes before making important decisions. Notably, the first signature of the four agencies on the document is that of then Regional Director of the BIA, Catherine Wilson.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs did write a letter of apology to the Goshute Tribal Chairman in 2006 for not consulting with the tribes on the SNWA project. The letter is breathtaking in its blasé quality. It reads, “BIA apologizes for not being able to consult with the tribe on the stipulated agreement and 3M (monitoring, mitigation and management) Plan before it was approved. The timing of the hearing and the negotiations on the stipulated agreement limited BIA’s ability to do so.” When you consider that the BIA endorsed a plan that would pump nearly 30 billion gallons of water per year out of Spring Valley, the ancestral and contemporary lands of the Goshutes–without consulting the Goshutes–because of “the timing of the hearings,” you might wonder what the word Indian has to do with The Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“They absolutely failed,” Echo Hawk says. They didn’t consult with the tribes when they entered these backroom agreements. They didn’t participate in the trial or show up at all. This was a classic example of non-Indian representatives that thought they knew better.”

Since The SNWA first decided it was going to build its hundreds of miles of pipeline and dozens of wells, both sides of the case have spent millions (if not tens of millions of dollars) fighting it out before the Nevada State Engineer and in court. The sides for and against the project have been whipsawed back and forth as the plans have gone through more than a dozen state, federal, and local agencies.

The plan went through iterations of being approved one year by the State Engineer only to be remanded by the district court judge another year. In 2007, the StateEngineer gave SNWA approval to pump 60,000 acre-feet of water per year (about 20 billion gallons) from Spring Valley. But in 2013, Judge Robert Estes of the seventh district court in Ely, Nevada, ordered the state engineer and the SNWA to rework their numbers and their plans calling the engineer’s decision “arbitrary and capricious.” Estes expressed strong doubts about the groundwater tables surviving the massive volumes of water being pumped. The state engineer appealed the case before the Nevada Supreme Court in 2014 and was rejected.

The various hearings, court cases, and legal complexities are too numerous to list here, but things came to a head in 2017 when the state engineer again held hearings.

“The trial had to be held in the Nevada legislature chamber in the Capitol building because of the number of parties, lawyers, and participants,” Echo Hawk said. “I thought it would have been appropriate to put signs on empty chairs for the BIA and other federal agencies who were absent. I was it for the tribes. In a giant room full of well-heeled Las Vegas lawyers and staff, it was David versus Goliath. Our tribal leaders and elders sitting in the gallery were wondering what the hell was going on and what was going to happen to the sacred Swamp Cedars and the water.”

At the hearing, Echo Hawk called Virgil Johnson, the Tribal Chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, and Rupert Steele, a Goshute tribal council member, as witnesses. In his testimony, Johnson said, “Swamp Cedars is a very sacred place. When we go there, we do some ceremony so we’re not disruptive of the spirits that are already there because of the massacre that happened. We want to make sure that we don’t upset those spirits. We always want to make sure that we’re in balance with the earth and with the sky and with the moon and with the sun and the wind and the animals and the plants and the trees and the rocks and the fish.”

His co-counsel member Rupert Steele said, “Each tree in the Swamp Cedars has its own spirit, tells its own story. Very strong story that we hold dearly.”

Despite very moving testimony by Johnson and Steele, despite Jones’s turning the SNWA’s water model on its head, despite Echo Hawk’s careful study and presentation of his case, and despite Hejmanowski’s skillful cross-examinations, the state engineer decided to go one more round with Judge Estes and appealed his 2013 decision.

But in March of 2020, Pat Mulroy’s dreams of piping groundwater from the north to sustain Las Vegas’s never-ending growth died in Judge Estes’s court, when he ruled against the state engineer’s appeal. In his decision, Judge Estes wrote, “Accordingly, this Court finds that the water appropriations in Spring Valley threaten to prove detrimental to the public interest because the awards, at the current well configuration, result in water mining, will never reach equilibrium, and will result in depletion of the Spring Valley aquifer.”

There are some paradoxes in this story. Hejmanowski, the lead counsel who fought the massive project to bring water to Las Vegas on behalf of the Mormon Church lives in Las Vegas and is painfully aware of its water shortage. Pat Mulroy didn’t just go after new sources of water but she also helped lead Las Vegas in developing one of the nation’s most innovative and successful water conservation programs. Despite professing to be a booster for growth, she is also a student of climate change and even wrote a book on the subject whose back cover reads, “When climate change is coupled with an explosion in human population and the staggering demands placed on water by industry and the high tech sector, it is no longer possible to ignore this precious resource.”

The story is also much bigger than what is written here and includes dozens more groups, landowners, a national park, extensive wildlife biology and plant physiology, and even landowners in Utah who weren’t about to let Nevada drain their aquifers.

But the story does show how time can bring two former enemies to the same side of a long battle. For it is only about 150 years after The Blackhawk War, a war that pitted Mormons against Indians and took so many lives, that the two communities found something that put them on the same side of a modern battle: precious, precious water.