by Emrys Westacott

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes….[1]

In other words, labour is the ultimate source of a society’s wealth. In feudal times it had been common to view land in this way since it was the basis for all agricultural produce, and the 18th century French physiocrats still championed that view. But Smith agreed with John Locke’s observation that a loaf of bread is not just produced by a baker but also, indirectly, by the work of the ploughman, the reaper, the thresher, the miller, the people who trained the oxen, mined iron for the plough, quarried stones for the mill, and so on. In fact, Locke argues,

if we rightly estimate things as they come to our use, and cast up the several expences about them, what in them is purely owing to nature, and what to labour, we shall find, that in most of them ninety-nine hundredths are wholly to be put on the account of labour.[2]

The idea that labour is the ultimate source of a nation’s wealth would seem to bolster the argument that that those who perform the labour should enjoy an appropriate share in the wealth that they create. This idea was certainly alive at the time of the English Revolution in the mid 17th century. The Digger leader Gerard Winstanley, claiming biblical authority for his position, denounced the enclosures of common land by the rich, arguing that God intended the Earth to be “a common store-house for all” and was dishonored by the idea that He approved of the current distribution of wealth, “delighting in the comfortable Livelihoods of some, and rejoicing in the miserable poverty and straits of others.”[3]

A century later, Adam Smith’s best friend, David Hume, although politically conservative, wrote:

Every person, if possible, ought to enjoy the fruits of his labour, in a full possession of all the necessaries, and many of the conveniences of life.[4]

Moreover, Hume recognized that acceptance of this principle would tend to promote equality, and saw this as a good thing since:

such an equality is most suitable to human nature, and diminishes much less the happiness of the rich than it adds to the poor.[5]

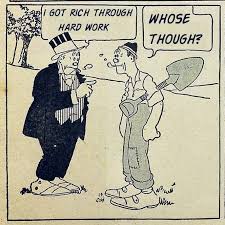

But an obvious question arises. If labour is the source of all wealth, and if people are entitled to enjoy the fruits of their labour, how can anyone justify the glaring inequalities in the way wealth is distributed? How can one avoid denouncing the poverty of the labouring masses relative to the prosperity of the leisured classes?

Locke explained, and by implication legitimized, inequality by tracing it back to moral differences between individuals.

God gave the world to men in common; but since he gave it them for their benefit, and the greatest conveniences of life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the industrious and rational, (and labour was his title to it;) not to the fancy or covetousness of the quarrelsome and contentious.[6]

So long as property consisted simply of land, he argues, no-one would have any incentive to own more than they could actually make use of. If my family can only consume the produce of two acres, what would be the point of owning more land than that? But with the invention of money, a form of property becomes available that one can amass, save, store indefinitely, and readily exchange for other goods and services that one desires. Money does not itself produce inequality; but it provides an incentive for people to work harder in order to become wealthier. Those who do so are doing God’s will, improving the world, and legitimately reaping the benefits of their moral superiority.

Locke thus tells a story of how an original equality eventually led naturally, and without anyone’s rights necessarily being violated, to a highly unequal distribution of wealth. He argues, further, that in societies where laws protect private property, the population have implicitly consented to the inequalities that have arisen.

Adam Smith offered an alternative countenancing of inequality. Labour may be the source of wealth, but there are other people, besides the labourers, who have a legitimate claim on the wealth produced: viz. those who risk their wealth through investments that make production possible. Even huge profits made on the backs of those who do most of the actual work are thus acceptable. They provide a return on investment, a reward for ingenuity and enterprise, and an incentive to others to follow the same path, thereby increasing the nation’s wealth..

As justifications for massive inequalities in the distribution of wealth, both of these rationalizations fall rather short. Viewed as history, Locke’s story of how a minority came to be fabulously rich while the majority came to be dispossessed is rather far-fetched, to put it mildly. Whether one is talking about the gaining of wealth and power by ruling classes in ancient times, or the enclosure of the commons and accumulation of capital described by Marx in the pages of Capital, it’s safe to say that the unabashed use of force, literal and legal, was usually the decisive factor.

Regarding Smith’s account, when it comes to investors being rewarded for risk-taking, the plain truth is that many investments simply aren’t that risky. When companies enjoy monopoly power over resources and patents, when armies and navies are deployed to protect commercial interests abroad, when laws are passed that force people into low-wage jobs and ban labour unions, and when those laws are enforced by troops, police, and the courts–when, in short, the state consistently sides with capital over labour, then investors can usually sleep easily in their beds. The point is readily admitted by Smith himself:

Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.[1]

Ideological descendants of the two justifications of inequality mentioned above are alive and well in various forms today. In fact, they still form part of the dominant ideology in countries like the US. If one attends to particular cases it is, to be sure, possible to find examples to illustrate the ideas. There are Andrew Carnegies and Oprah Winfreys who, through hard work, talent, perseverance (and luck) go from rags to riches. There are entrepreneurial spirits, like James Dyson (inventor of the Dual Cyclone vacuum cleaner) who risk everything to pursue their goal and eventually become fabulously wealthy.

But it is important to understand the production and distribution of wealth in more general terms–which is to say, in terms of class, conceived on a global scale.

The class structure of society is undeniably more complex now than in the days of Smith or Marx. Back then, the distinction between the working class, who lived entirely by selling their labour power, and those who didn’t need to work was sharper and more visible. For one thing, what was once the leisure class has today become less leisured. Its members in fact now like to boast about how hard they work (in some cases, no doubt, to persuade themselves that they “earn” their obscenely high salaries). Nevertheless, the underlying structure governing the production and distribution of wealth remains essentially the same.

Even in Marx’s time, the majority of those who lived off the fruits of others’ labour were not fat, top-hatted owner of mines and mills driving their emaciated workers into an early grave. They were genteel types who enjoyed a steady income–perhaps a very modest one–from investments that yielded a return: some combination of profits, dividends, capital gains, rents, and interest. Such people populate the novels of Austen, Dickens, and Trollope, usually as respectable, decent types. Attention is rarely, if ever, drawn to the fact that their respectability rests on them enjoying an unearned share in the fruits of other people’s labours.

Today, the same pattern still obtains. Millions around the world, from McDonalds restaurants in Los Angeles to Apple factories in Zhengzhou to farms and plantations around the globe, labour for long hours performing tedious, exhausting tasks for low wages. Their work creates wealth, most of which goes to other people who don’t have to do that kind of work. In some cases, the flow of fortune is relatively simple to track: around 800,00 people work for Amazon, and much of the wealth they create goes to Jeff Bezos and the other leading shareholders in the company. Elsewhere, the lines are somewhat veiled. For instance, CEOs and other top administrators of (supposedly) nonprofit organizations like hospitals and universities often pull down disgustingly high salaries, and these are made possible by their institutions’ portfolio of investments.

But even those of us who don’t consider ourselves especially rich or highly paid, if we receive, or plan to receive, income from investments–and that includes virtually everyone with a private or employer-supported pension plan–are essentially in the same category. Just about any diversified pension fund will rely heavily on owning stocks in Amazon, Apple, and countless other companies that employ thousands of poorly paid workers.

But even those of us who don’t consider ourselves especially rich or highly paid, if we receive, or plan to receive, income from investments–and that includes virtually everyone with a private or employer-supported pension plan–are essentially in the same category. Just about any diversified pension fund will rely heavily on owning stocks in Amazon, Apple, and countless other companies that employ thousands of poorly paid workers.

Today, the fruits of the labours of the poorly paid are certainly distributed far more widely than in the past. This is the system we have at present, and it is unlikely to change any time soon. Moreover, one can argue, with some plausibility, that it is a system which has brought greater security to millions of lives. Nevertheless, the ancient injustice still persists. The people who do most of the work, perform the least enviable tasks, and who are largely responsible for the creation of wealth in the world, receive the smallest share in the fruits of their labour. Most of that wealth goes to people who have not done the work, who are much better off, and who need it much less.

[1] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. xxiii.

[2] Locke, Second Treatise, Ch. V.

[3] Gerard Winstanley, The True Levellers Standard Advanced: Or, The Sate of Community Opened, and Presented to the Sons of Man (1649).

[4] David Hume, Of Commerce.”

[5] David Hume, “Of Commerce.”

[6] Locke, Second Treatise, Ch. V