by Philip Graham

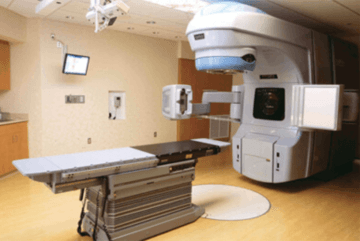

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

“Oh,” I replied, startled by this sudden personal offering. “Were you injured?”

“Yeah, my foot. So bad that the doctors said I might not walk on it again.”

“But here you are,” I observed. Then I asked the question he clearly wanted to answer. “How’d you get better?”

“Well, I read that a cat’s purr vibrates at just the right hertz cycles per second to be a healing vibration.”

This was news to me. Wondering if this fellow was simply a feline obsessive, I tested that theory by asking, “Hmm, how many cats do you own?”

“None! I don’t like cats much. So I thought, maybe there’s another way. If the vibrations of a cat’s purring can heal you, why not the vibrations of music? I set up stereo speakers on either side of my foot, and sat there all day, day after day.”

“It really worked?”

He grinned. “Here I am.”

His boss called back: questions asked and answered, and job soon completed. Only after he left did I realize I never found out what sort of music he’d listened to. I am not, generally, a suspicious person, but since Internet service was back and running I typed in a search combining cats, hertz, healing, and music, to make sure I wasn’t being joshed. Indeed, there are “nursing cats” who can purr you to health. Checking deeper, I discovered that a lot of music is tuned to just the right magical hertz level to lurk in songs and symphonies. Melody doubling as medicine? Certainly in my life, listening to music has been as essential as breathing, so why not healing as well?

Now I lie on the linear accelerator’s mobile tray and hope this big machine possesses a proper purr.

The technicians gently arrange my body in place, so that a beam of radiation will hit only offending hidden tissue. They align my recent black dot of permanent ink—a nondescript, medically-approved bull’s eye—to just the right spot. I’m given a soft, yellow rubber donut to hold, which looks like something dog and dog owner would tussle with if in the mood for some tug-of-war roughhouse. Here in the radiation room it will prevent me from absentmindedly moving my arms during any crucial moment.

Everyone attends to this prep work in a professional and friendly, if slightly generic, manner. I’d love to chat with them, attempt a joke or two, because that’s just the way I am.

In my four-years-ago kitchen, only a fews days into a new life in Rhode Island, when that cable guy offered me his story unbidden I had to resist hugging him in gratitude. I had lived for over thirty years in a Midwestern region of such public politeness that I could rarely get a conversation going with anyone outside of friends or colleagues. This would have driven my father crazy, a man who loved to chat up anyone he met—someone else on line to the cash register, even a coin collector in a toll booth. His friendliness became his career’s success, keeping small business tenants happy in the buildings he managed in New York City.

That cable guy made me realize how living in the Midwest had oppressed me not only because of its flat physical landscape, but also because of its too often flat emotional landscape.

Yet as much as I like to chat with strangers, now is not the time to distract medical professionals from mapping out an ideal electron beam path to my cancer cells. I’ve waited too long for this moment—my treatment has already been delayed because of the pandemic. At the height of that first terrible spring surge, the entrance to Massachusetts General Hospital was overwhelmed with deliveries of the Covid sick. All the nurses and doctors I see in the hallways, these technicians beside me, were commandeered for emergency pandemic duty, and they must have gone through more than I can imagine. Now this hospital is one of the safest places on earth, my doctor assures me—everyone wears a mask and obsessively washes hands, while the entire building is regularly scrubbed down with near-religious fervor.

Yet as much as I like to chat with strangers, now is not the time to distract medical professionals from mapping out an ideal electron beam path to my cancer cells. I’ve waited too long for this moment—my treatment has already been delayed because of the pandemic. At the height of that first terrible spring surge, the entrance to Massachusetts General Hospital was overwhelmed with deliveries of the Covid sick. All the nurses and doctors I see in the hallways, these technicians beside me, were commandeered for emergency pandemic duty, and they must have gone through more than I can imagine. Now this hospital is one of the safest places on earth, my doctor assures me—everyone wears a mask and obsessively washes hands, while the entire building is regularly scrubbed down with near-religious fervor.

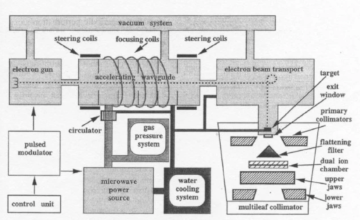

The linear accelerator’s various panels begin to shift and move, and because I am claustrophobic I close my eyes to the enclosing contours of the machine. I squeeze the squeezy donut against my chest, and arrive at something resembling relaxation. There is no pain, only ugly noises burping from the accelerator.

So much for healing music! The radiation machine sounds a bit like the old AOL dial-up tone, bing bang bong, and krssssssh, minus the announcement of mail, and plus a fluid rrrrrrrrrrr sound resembling a rotary floor polisher.

If this were music, the score might look a bit complicated.

If this were music, the score might look a bit complicated.

This sequence repeats again and again, and in between I finally notice the snippets of a song in the background— the hospital’s Spotify music feed. Ah, music! Healing’s one-two punch: radiation beams paired with melody and harmony. The song is just loud enough for me to catch a hint of its power pop’s arrangement and a man and woman harmonizing this scrap of lyrics: “I don’t know what love is, but I think it might be you.” Not exactly a full endorsement of future bliss, but hopeful enough.

Before I know it, I’m released from the maw of the radiation machine. My time as a target today has lasted only about five minutes. I open my eyes, thank the surrounding technicians, and return to the dressing room for my clothes and for my writing notebook, where I write down that song’s refrain.

Since the hospital won’t allow a patent’s spouse or other close relative inside, all for the necessity of a more controlled social distancing, my wife Alma has to stay behind in a nearby suburb’s apartment that we’re renting for my month of irradiation. When I drive back, she has lunch waiting and a full raft of questions about my first day.

In the afternoon I remember to attempt a Google search for the lyrics. That harmonizing couple turns out to be Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper, from A Star is Born, a movie I never got around to watching.

The pace plods too much for my taste. Curiosity appeased, my mind lets the song go. I have Chick Corea’s jazz classic, “Spain,” to appreciate instead. It seems to have invented its own form of swing, the melody rising, and falling, and then a careening rhythm section takes over the bridge, and that flute solo comes in, and I keep the song on repeat throughout the afternoon. I’m writing into my first attempt at a 3 Quarks Daily music column, and I want to do this song justice.

After dinner, Alma and I fit masks to our faces and venture out to a nearby reservoir, for a two-mile double circuit along its gravelly oval path. Only a few other people share this calming refuge, perhaps out of Covid fear, and Alma and I freely talk out our day. These past several months have been hard on her—quarantines and lockdowns have kept us from our children and grandchildren, and I sense that the invisible question mark of my health has driven her at times to silent worry.

The following day, I come home with another captured lyric snippet, another ambivalent romantic refrain: “I think I want to marry you.” Bruno Mars, it turns out, is the one considering the marrying, though I soon realize that the word “marry” stands in for a far more informal arrangement, and we’re more in the territory of an 18th century carpe diem seduction poem.

The song itself is infectious, the sinuous synthesizer punctuated by finger snapping, and chimes that evoke wedding bells. An improvement over yesterday’s song, but still not enough to keep me from playing and replaying Chick Corea’s “Spain” until dinner.

Over the next few days, Alma and I establish a routine—my drive to and from the hospital, with an essential radiation treatment fit in the middle, then her presentation of a Welcome Home Lunch, followed by some pop song detective work, maybe a nap if needed afterwards, and my listening to “Spain” (deadline fast approaching). Alma works on writing emergency Covid relief grant proposals for the Cape Verdean community in Rhode Island that she studies. Then dinner (cooking duties shared, if I’m feeling peppy), and afterward, we indulge in our reservoir walk-and-talk ritual until breathtaking sunsets.

Over the next few days, Alma and I establish a routine—my drive to and from the hospital, with an essential radiation treatment fit in the middle, then her presentation of a Welcome Home Lunch, followed by some pop song detective work, maybe a nap if needed afterwards, and my listening to “Spain” (deadline fast approaching). Alma works on writing emergency Covid relief grant proposals for the Cape Verdean community in Rhode Island that she studies. Then dinner (cooking duties shared, if I’m feeling peppy), and afterward, we indulge in our reservoir walk-and-talk ritual until breathtaking sunsets.

I’ve come to appreciate routine.

Back in January, at the first meeting with my oncologist, he confidently laid out the plan that would become the course of treatment. First, you will take this pill. A week later you will receive this shot, and then we wait. Then we’ll complete a mapping procedure, and soon after, a month of radiation, weekends off. Finally, a surgery. End of recipe.

The structure of this treatment still bestows the comfort of routine: this, then that, then more of that, then some of this, and so on. The invisible virus now out and about in the world is far less predictable, far more threatening: it can deal death in a breeze, or await your unfortunate touch of an otherwise innocent hand railing or doorknob.

So, I follow a simple cancer recipe, and I don’t even have to do the cooking. The cooking is done to me.

I don’t normally favor the predictable. In the kitchen, recipes are designed to defeat the unforeseen, but I rarely employ them unless I find myself up against the invisible, ever-shifting wall of my culinary ignorance. Then it’s time to consult an expert. Usually, though, I’ll intuit that the braised broccoli needs a friend in the simmering pan. I have cherry tomatoes too old for salad, but they’d do well if heated into a sauce, eventually clinging to the nooks and crannies of broccoli noggins. And maybe a few strips of sweet yellow pepper can be added at the end, to add a burst of color and crunch?

*

By the second week, I can predict the pauses between the accelerator’s stomach growlings, when a song’s crucial refrain might easily be grasped. There’s something of the chase in this interrupted listening that I like. In my teens, I had to wait for my current favorite song to make its appearance in a radio station’s rotation, or turn the dial back and forth across the spectrum in search of another station that might be playing that song’s irresistible hook.

Yet when I concentrate on these latest hit songs in the radiation room’s background, I have little context about who is singing. Sometimes, without the name of a musician I might visualize, I find it hard to retain what I hear. The song becomes a puff of smoke I can’t gather from the air. Though it does help when a few words of a song are repeated ad infinitum, like “I could be the one.”

No arduous detective work back home is necessary for this lyric. “Be the One,” by Dua Lipa, pops right up on the computer screen.

When I’m able to hear a full lyric, sometimes a surprise awaits. In this case, “I could be the one” isn’t a plea to start a relationship, as I’d assumed; instead, the singer is asking for another chance. She’s done something bad, her lover has left her, and this song serves as her hope for amends.

In the days that follow, the words “Baby, why can’t you meet me in the middle?” leads me to a song by Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey; “I love your body, I love the shape of you” delivers me to Ed Sheeran; and “A little bit psycho” reveals Ava Max’s hit song, “Sweet But Psycho.”

Normally, I don’t listen much to the Top Forty, or whatever it’s called these days. At home, I don’t listen to music on the radio (I prefer choosing from a stack of favored CDs), and in the car it has been news news news since 2016’s election apocalypse. In a sense, I face a stranger country with the hospital’s music feed than I do with the small principality of a linear accelerator. These unfamiliar power pop ballads, catchy yet somehow forgettable melodies, overly emotional vocals and overproduced music, seem too relentlessly, predictably aimed at a wide audience.

It’s true I’ve come to appreciate predictability in medical treatment. Not so much in music.

I don’t necessarily dislike these songs whose identities I search out—by now, out of habit—but ultimately, they skim over the surface of me. They don’t pass the Should-it-go-or should-it-stay test I developed when, in the months before Alma and I moved from Illinois to Rhode Island, I needed to cull my book and record collection, narrow it down to a less unreasonable caravan of cardboard boxes.

Eventually, I revised my test’s name to “Performer or Artist?”

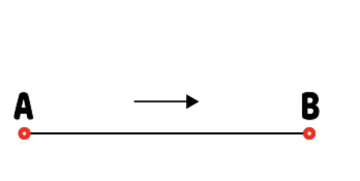

As I see it, a performer aims a song or a story directly at the audience, seeking to impress and awe. The ambition is immediate impact. The line from performer to audience is as direct as A to B.

As I see it, a performer aims a song or a story directly at the audience, seeking to impress and awe. The ambition is immediate impact. The line from performer to audience is as direct as A to B.

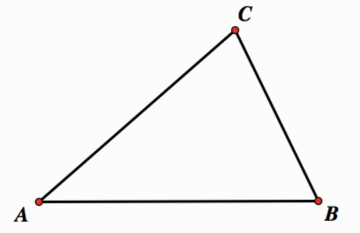

An artist, however, aims a song or story at some hidden inner landscape, or to someone not present physically but still in need to addressing or confronting. Here, the chart of transmission complicates. C here stands for that secret someone or something. Now the nominal audience (B) is placed in the position of eavesdropper. We’ve gone from a straight line to a triangle, we’ve expanded to the possibilities of geometry. I believe that leap into unspoken complexity is unconsciously recognized by most listeners or readers.

An artist, however, aims a song or story at some hidden inner landscape, or to someone not present physically but still in need to addressing or confronting. Here, the chart of transmission complicates. C here stands for that secret someone or something. Now the nominal audience (B) is placed in the position of eavesdropper. We’ve gone from a straight line to a triangle, we’ve expanded to the possibilities of geometry. I believe that leap into unspoken complexity is unconsciously recognized by most listeners or readers.

By now, in my last two weeks of radiation room visits, I’ve begun working on my second essay for 3 Quarks Daily, and I already have a title: “Nothing Else Sounds Quite Like This.” It’s meant as a kind of praise poem to whatever is brilliant and soulful in artists you may have never heard of.

I’m concentrating on the music of Annabel (lee), the duo of Richard and Sheila Ellis. Every day, as I drive to and from the radiation room, I crank up their music in my air-conditioned car and seek out the arrangement’s nuances, unimpeded by the interruptions of a linear accelerator. No krsssssh, no bings and boings, only the occasional car honking at who knows what, or some bad driver’s too swift weave in and out of the lanes. As I listen, I’m more convinced than ever that Annabel (lee) fits my private definition of artist, not performer. One day I can’t stop repeating the song “Far,” perhaps at first because of this sliver of lyric: “It matters not if others cannot hear.” That’s just the attitude I need after weeks of delving into hit songs and their calculations of popularity. And yet, everyone should hear Richard Ellis’ languid, samba-like guitar strumming in this song, and Sheila Ellis’ subtle channeling of Billie Holiday and Nina Simone, the finger snap substitution for drums, the slow, curling, melodic twists of an Ondes Martenot, and a string section brooding quietly at the edges while Sheila sings, “If you dare to dream, I’ll show you all my stories.”

I’m concentrating on the music of Annabel (lee), the duo of Richard and Sheila Ellis. Every day, as I drive to and from the radiation room, I crank up their music in my air-conditioned car and seek out the arrangement’s nuances, unimpeded by the interruptions of a linear accelerator. No krsssssh, no bings and boings, only the occasional car honking at who knows what, or some bad driver’s too swift weave in and out of the lanes. As I listen, I’m more convinced than ever that Annabel (lee) fits my private definition of artist, not performer. One day I can’t stop repeating the song “Far,” perhaps at first because of this sliver of lyric: “It matters not if others cannot hear.” That’s just the attitude I need after weeks of delving into hit songs and their calculations of popularity. And yet, everyone should hear Richard Ellis’ languid, samba-like guitar strumming in this song, and Sheila Ellis’ subtle channeling of Billie Holiday and Nina Simone, the finger snap substitution for drums, the slow, curling, melodic twists of an Ondes Martenot, and a string section brooding quietly at the edges while Sheila sings, “If you dare to dream, I’ll show you all my stories.”

I love Annabel (lee)’s records so much I’m back to my old tricks of sharing songs with innocent bystanders. On my last day’s journey to the radiation room, in the hospital parking lot I roll down the window in order to swipe my month’s pass card, and I realize one of my favorite passages in Annabel (lee)’s “Paris 1914” has begun, when a violin glides a counter-melody above the rhythm section. I lower the window further and turn up the volume, so whoever’s in the car waiting behind me can enjoy the moment too.

I can’t help it, I prefer music that avoids the established recipe and aims for something that, however carefully constructed, sounds like improvisation and offers entry to a little used path. That’s the sort of music that will always resonate inside me like a cat’s purr.

Recovery Coda

It’s the beginning of June, 2021, in the middle of a vaccine roll out that has reached over 60% of Americans and counting. A maskless summer tentatively beckons. The eligible members of my extended family are vaccinated. I am recovered from cancer, and the risk of eventual recurrence is vanishingly small.

I’m sitting in the living room, listening to Wynton Marsalis’ joyous “Democracy! Suite.” Once that jazzy celebration skates to its last song, I intend to slip into the CD player guitarist Titi Robin’s “Kali Sultana,” or maybe Carla Morrison’s “Amor Supremo Desnudo,”or Toumani Diabaté’s “Mande Variations.” Or all of them, in whatever order. I like to listen to music when I write, I like my mind to bounce off a shifting map of sound.

And I’m writing now, finishing this last column for my year’s run at 3 Quarks Daily, not quite willing to set the last word to paper.

I like to think that every music column I’ve written this past year has added to my recovery, become a secret anthology of healing, a private medicine cabinet of music’s inexhaustible joys. My many thanks to all who gave me the opportunity to write these essays, and to anyone who read them and may have reconnected to their own musical joys. And, of course, my deep thanks to a world-class medical team, without whom these twelve columns might have been written in an increasingly minor key.