Ellen Wexler in Smithsonian:

On her 25th birthday in February 1947, Felicia Montealegre sent a giddy letter to her new fiancé. “Lenny, my darling, my darling!” she wrote. “I am a quarter of a century old, a very frightening fact!” Recent developments, she went on, included the arrival of a black cocker spaniel puppy (“She’s mine, my very own!”) and an impending driver’s license exam (“I drive alone all over the place, up hill and down dale, heavy traffic and all—and I’m great! So there!!”).

On her 25th birthday in February 1947, Felicia Montealegre sent a giddy letter to her new fiancé. “Lenny, my darling, my darling!” she wrote. “I am a quarter of a century old, a very frightening fact!” Recent developments, she went on, included the arrival of a black cocker spaniel puppy (“She’s mine, my very own!”) and an impending driver’s license exam (“I drive alone all over the place, up hill and down dale, heavy traffic and all—and I’m great! So there!!”).

Felicia, an actress, had been engaged to Leonard Bernstein, the 28-year-old wunderkind composer and conductor, for two months. She was, like most everyone in the man’s orbit, perilously in love with him. Still, beneath the bubbly, starry-eyed adoration, she felt something was amiss. “What’s with you?” she wrote. “You never really tell me how you feel—is it that difficult?” Come fall, the engagement was off. Then, after a four-year interlude, it was back on. A wedding quickly followed.

Yet the biggest obstacle remained: Bernstein, a closeted bisexual man, had always conducted numerous affairs with both men and women. In 1947, the secrecy had been evidently too heavy for the relationship to bear.

More here.

As a health reporter who’s been following nutrition news for decades, I’ve seen a lot of trends that made a splash — and then sank. Remember olestra, the Paleo diet and celery juice? Watch enough food fads come and go, and you realize that the most valuable nutrition guidance is built on decades of research, in which scientists have looked at a question from multiple perspectives and arrived at something like a consensus.

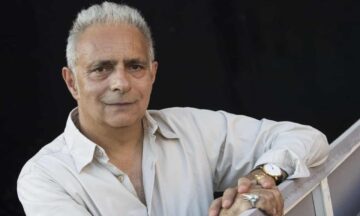

As a health reporter who’s been following nutrition news for decades, I’ve seen a lot of trends that made a splash — and then sank. Remember olestra, the Paleo diet and celery juice? Watch enough food fads come and go, and you realize that the most valuable nutrition guidance is built on decades of research, in which scientists have looked at a question from multiple perspectives and arrived at something like a consensus. Hanif Kureishi has spoken candidly of how his sense of self and privacy have been “completely eradicated” after a fall on Boxing Day last year left him unable to use his hands, arms or legs.

Hanif Kureishi has spoken candidly of how his sense of self and privacy have been “completely eradicated” after a fall on Boxing Day last year left him unable to use his hands, arms or legs. People often think they know what causes chronic depression. Surveys indicate that more than 80% of the public blames a “chemical imbalance” in the brain. That idea is widespread in pop psychology and cited in

People often think they know what causes chronic depression. Surveys indicate that more than 80% of the public blames a “chemical imbalance” in the brain. That idea is widespread in pop psychology and cited in  It is worth remembering the vast majority of what we call free-speech issues have little basis in the First Amendment, which only forbids the abridgment of speech by the government, not private organizations like magazines, cultural centers, or Hollywood production companies. In most states, for instance, it is perfectly legal for employers to fire workers for speech, as a

It is worth remembering the vast majority of what we call free-speech issues have little basis in the First Amendment, which only forbids the abridgment of speech by the government, not private organizations like magazines, cultural centers, or Hollywood production companies. In most states, for instance, it is perfectly legal for employers to fire workers for speech, as a  January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well. The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when

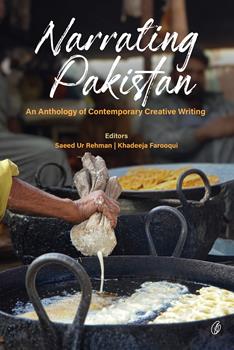

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.

Sughra Raza. Breaking Point.