Daniel C. Dennett in Philosophy Now:

In a paper published in Synthese (#53) in 1982, ‘Contemporary Philosophy of Mind’, Richard Rorty wrote an enthusiastic account of the revolutionary ‘Ryle-Dennett tradition’. Was I really as radical a revolutionary as he said I was? I responded mischievously, perhaps rudely:

In a paper published in Synthese (#53) in 1982, ‘Contemporary Philosophy of Mind’, Richard Rorty wrote an enthusiastic account of the revolutionary ‘Ryle-Dennett tradition’. Was I really as radical a revolutionary as he said I was? I responded mischievously, perhaps rudely:

“Since I, as an irremediably narrow-minded and unhistorical analytic philosopher, am always looking for a good excuse not to have to read Hegel or Heidegger or Derrida or those other chaps who don’t have the decency to think in English, I am tempted by Rorty’s performance on this occasion to enunciate a useful hermeneutical principle, the Rorty Factor:

Take whatever Rorty says about anyone’s views and multiply it by .742.

After all, if Rorty can find so much more in my own writing than I put there, he’s probably done the same or better for Heidegger – which means I can save myself the trouble of reading Heidegger; I can just read [Rorty’s book] Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton University Press, 1979) and come out about 40% ahead while enjoying my reading at the same time.”

Rorty took this in good spirits and continued his amiable practice of highlighting the connections he saw between analytic philosophers’ arguments and the grand march of isms that constitute Western philosophy. Part of his optimistic genius was seeing how other people’s hard work in the trenches might be seen as major steps of genuine philosophical progress. This collection of previously unpublished works, most of them lectures delivered on multiple occasions, shows his power, his insight, his constructive spirit throughout. It is indeed enjoyable and enlightening philosophical reading, although I now believe that philosophers really shouldn’t rely on Rorty and other like-minded scholars of the field to frame our projects.

More here.

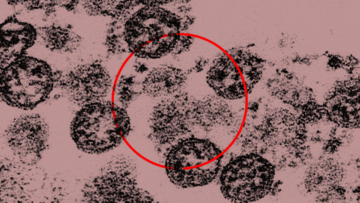

My breakthrough infection started with a scratchy throat just a few days before Thanksgiving. Because I’m vaccinated, and had just tested negative for COVID-19 two days earlier, I initially brushed off the symptoms as merely a cold. Just to be sure, I got checked again a few days later. Positive. The result felt like a betrayal after 18 months of reporting on the pandemic. And as I walked home from the testing center, I realized that I had no clue what to do next.

My breakthrough infection started with a scratchy throat just a few days before Thanksgiving. Because I’m vaccinated, and had just tested negative for COVID-19 two days earlier, I initially brushed off the symptoms as merely a cold. Just to be sure, I got checked again a few days later. Positive. The result felt like a betrayal after 18 months of reporting on the pandemic. And as I walked home from the testing center, I realized that I had no clue what to do next. We know by now that authoritarian populists have handled the Covid-19 pandemic badly. Both Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro presided over spiraling death rates, fueled by a disregard for medical science and neglect of public health imperatives.

We know by now that authoritarian populists have handled the Covid-19 pandemic badly. Both Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro presided over spiraling death rates, fueled by a disregard for medical science and neglect of public health imperatives. Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation.

Harvard Medical School professor of neurology Rudolph Tanzi discusses how lifestyle choices can help maintain brain health during a person’s lifespan. Topics include Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia, the role of genetics and environment in health, and the importance of sleep, exercise, and diet in controlling neuroinflammation. I have a childhood memory of looking in the bathroom mirror, and for the first time realizing that my experience at that precise moment—the experience of being me—would at some point come to an end, and that “I” would die. I must have been about 8 or 9 years old, and like all early memories this one too is unreliable. But perhaps it was at this moment that I also realized that if my consciousness could end, then it must depend in some way on the stuff I was made of—on the physical materiality of my body and my brain. It seems to me that I’ve been grappling with this mystery, in one way or another, ever since.

I have a childhood memory of looking in the bathroom mirror, and for the first time realizing that my experience at that precise moment—the experience of being me—would at some point come to an end, and that “I” would die. I must have been about 8 or 9 years old, and like all early memories this one too is unreliable. But perhaps it was at this moment that I also realized that if my consciousness could end, then it must depend in some way on the stuff I was made of—on the physical materiality of my body and my brain. It seems to me that I’ve been grappling with this mystery, in one way or another, ever since.

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.