by Carol A Westbrook

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone.

The wooden crate and the Christmas Eve feast were Polish traditions. This is not surprising since my grandparents were only a few decades away from their life in Poland, when they left the to marry and raise a family in Chicago. Like most of the other folks in our neighborhood, we still had strong ties to Polish customs and religion.

Our Catholic religion was full of magic, which we took for granted. Prayers to St. Anthony would help you find something you lost. Want something really, really bad? Say a novena, for 9 days of prayer. St. Jude can help solve hopeless cases, like cancer. If you were paralyzed or had some other awful condition, you might make a pilgrimage to Lourdes, in hopes of a cure. Many were cured there. Read more »

Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up. Only two of the following three cultures are, as far as we know, real. In 2022, perhaps, I will reveal which of them I made up.

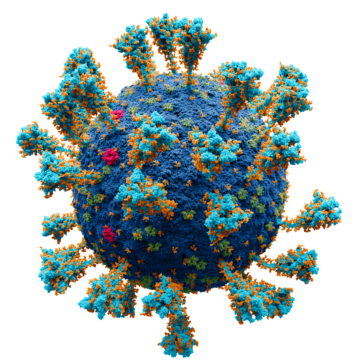

Only two of the following three cultures are, as far as we know, real. In 2022, perhaps, I will reveal which of them I made up. The preliminary data about omicron and vaccines is

The preliminary data about omicron and vaccines is  French far-right pundit Éric Zemmour recently launched his presidential campaign with a

French far-right pundit Éric Zemmour recently launched his presidential campaign with a  On December 15, 2011, Comet Lovejoy plunged through the sun’s corona

On December 15, 2011, Comet Lovejoy plunged through the sun’s corona  I

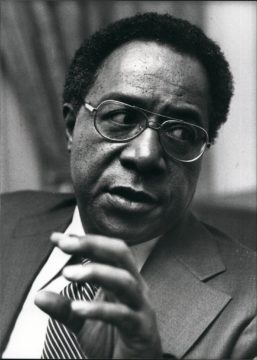

I In 1959, long before his books “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” and “Roots” made him famous, an aspiring writer named Alex Haley, fresh out of the Coast Guard, wrote to six prominent Black writers in Greenwich Village for pointers on how to break into publishing. Only James Baldwin replied, showing up at Haley’s place unannounced one afternoon and chatting with him. Haley was eternally grateful for such generous encouragement from the distinguished author.

In 1959, long before his books “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” and “Roots” made him famous, an aspiring writer named Alex Haley, fresh out of the Coast Guard, wrote to six prominent Black writers in Greenwich Village for pointers on how to break into publishing. Only James Baldwin replied, showing up at Haley’s place unannounced one afternoon and chatting with him. Haley was eternally grateful for such generous encouragement from the distinguished author. Raphaële Chappe in Late Light:

Raphaële Chappe in Late Light: Herman Mark Schwartz in American Affairs Journal:

Herman Mark Schwartz in American Affairs Journal: Ian Hesketh in Aeon:

Ian Hesketh in Aeon:

Marco Roth in Tablet:

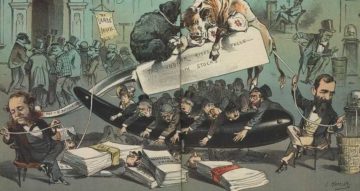

Marco Roth in Tablet: Throughout much of human history, famine, pestilence, and war have sent people seeking the comforts of religion. From the religious processions of Europe during the fourteenth-century Black Plague to the sharp

Throughout much of human history, famine, pestilence, and war have sent people seeking the comforts of religion. From the religious processions of Europe during the fourteenth-century Black Plague to the sharp  What is the matter with the Democrats? On one level, the answer is simple. Voters with college degrees are

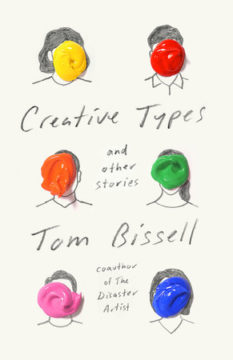

What is the matter with the Democrats? On one level, the answer is simple. Voters with college degrees are  This kind of career serenity prayer led to Bissell’s biggest breakthrough: “

This kind of career serenity prayer led to Bissell’s biggest breakthrough: “