Bill Gates in his blog:

In my previous end-of-year post, I wrote that I thought we’d be able to look back and say that 2021 was an improvement on 2020. While I do think that’s true in some ways—billions of people have been vaccinated against COVID-19, and the world is somewhat closer to normal—the improvement hasn’t been as dramatic as I hoped. More people died from COVID in 2021 than in 2020. If you’re one of the millions of people who lost a loved one to the virus over the last twelve months, you certainly don’t think this year was any better than last.

In my previous end-of-year post, I wrote that I thought we’d be able to look back and say that 2021 was an improvement on 2020. While I do think that’s true in some ways—billions of people have been vaccinated against COVID-19, and the world is somewhat closer to normal—the improvement hasn’t been as dramatic as I hoped. More people died from COVID in 2021 than in 2020. If you’re one of the millions of people who lost a loved one to the virus over the last twelve months, you certainly don’t think this year was any better than last.

Because of the Delta variant and challenges with vaccine uptake, we’re not as close to the end of the pandemic as I hoped by now. I didn’t foresee that such a highly transmissible variant would come along, and I underestimated how tough it would be to convince people to take the vaccine and continue to use masks.

I am hopeful, though, that the end is finally in sight. It might be foolish to make another prediction, but I think the acute phase of the pandemic will come to a close some time in 2022.

More here.

The discovery of a Standard Model-like Higgs boson was a great triumph for renormalisable field theory, and really for simplicity. By the time the LHC was operating, attempts to make the Standard Model (SM) work without an elementary Higgs field – using a dynamical mechanism instead – had become rather convoluted. It turned out that, as far as one can judge from what we have learned so far, the original idea of an elementary Higgs particle was correct. This also means that nature takes advantage of all the possible building blocks of renormalisable field theory – fields of spin 0, 1/2 and 1 – and the flexibility that that allows.

The discovery of a Standard Model-like Higgs boson was a great triumph for renormalisable field theory, and really for simplicity. By the time the LHC was operating, attempts to make the Standard Model (SM) work without an elementary Higgs field – using a dynamical mechanism instead – had become rather convoluted. It turned out that, as far as one can judge from what we have learned so far, the original idea of an elementary Higgs particle was correct. This also means that nature takes advantage of all the possible building blocks of renormalisable field theory – fields of spin 0, 1/2 and 1 – and the flexibility that that allows. The popular narrative goes that history is governed by evolutionary forces. While there are exceptions to every rule, its broad sweep pushes in a general direction that is predictable and obvious. Before the rise of agriculture, humans lived in small egalitarian bands. It’s been downhill ever since, as our species trends increasingly toward domination and arbitrary hierarchy.

The popular narrative goes that history is governed by evolutionary forces. While there are exceptions to every rule, its broad sweep pushes in a general direction that is predictable and obvious. Before the rise of agriculture, humans lived in small egalitarian bands. It’s been downhill ever since, as our species trends increasingly toward domination and arbitrary hierarchy. It’s Christmas in Paris and Les Champs-Elysees is appropriately adorned. We are, after all, in the so-called Elysian Fields, paradise, heaven on earth. Red illuminated trees line both side of France’s most famous avenue, stars fill the sky and the red carpet is laid out in front of the prestigious Gaumont cinema. The welcome is fit for royalty. And, on cue, Jesus turns up.

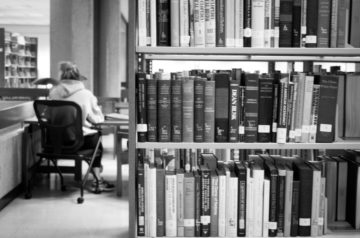

It’s Christmas in Paris and Les Champs-Elysees is appropriately adorned. We are, after all, in the so-called Elysian Fields, paradise, heaven on earth. Red illuminated trees line both side of France’s most famous avenue, stars fill the sky and the red carpet is laid out in front of the prestigious Gaumont cinema. The welcome is fit for royalty. And, on cue, Jesus turns up. I’ve begun to fear that requiring my existentialism students to bring real books to class is . . . well, absurd. Absurd not just in the everyday sense of ridiculous, but absurd in the Camusian sense as well. Is it just as unreasonable to demand that students use an ancient technology as it is to demand that an indifferent universe offers us meaning? It might be the case that my traditional expectations of students are unreasonable. More than a few students, rather than bringing paperbacks of the assigned works, bring printouts. At best, this means they haven’t the means to buy the book; at worst, it means they find unmeaningful the very possession of the book. They have no more intention to keep a printout—to reread or reflect upon it—than I have the intention to keep yesterday’s newspaper.

I’ve begun to fear that requiring my existentialism students to bring real books to class is . . . well, absurd. Absurd not just in the everyday sense of ridiculous, but absurd in the Camusian sense as well. Is it just as unreasonable to demand that students use an ancient technology as it is to demand that an indifferent universe offers us meaning? It might be the case that my traditional expectations of students are unreasonable. More than a few students, rather than bringing paperbacks of the assigned works, bring printouts. At best, this means they haven’t the means to buy the book; at worst, it means they find unmeaningful the very possession of the book. They have no more intention to keep a printout—to reread or reflect upon it—than I have the intention to keep yesterday’s newspaper. Although the jungles of southern Mexico seem like an ideal spot for fieldwork, the region’s sulfur springs are far from a tropical getaway. In addition to the area’s stifling heat, the pools reek of rotten eggs. Their milky, turquoise water is even more inhospitable: it is laced with toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide and contains very little oxygen.

Although the jungles of southern Mexico seem like an ideal spot for fieldwork, the region’s sulfur springs are far from a tropical getaway. In addition to the area’s stifling heat, the pools reek of rotten eggs. Their milky, turquoise water is even more inhospitable: it is laced with toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide and contains very little oxygen. B

B George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged.

George Steiner was called many things across his lengthy writing career—sage, pedant, philosopher, snob, the last great European intellectual, a “mimic” staging a decades-long “impression of the world’s most learned man”—but the title he always claimed for himself was simply critic. As we reflect on the meaning of Steiner’s work in the wake of his death in February 2020, that self-characterization cannot be forgotten. Steiner was in many ways a formidable scholar, and his commentaries on core texts (Antigone, The Brothers Karamazov, the poetry of Paul Celan) and enduring themes (tragedy, translation, the inhuman) will surely be cited for many years to come. Yet from the beginning of his career in the late fifties to his last notable works at the turn of the century, he was explicitly engaged in the practice of criticism—the goal of which was to reach the wider republic of readers (not just academicians) with his urgent dispatches on the state of the arts and culture. It was as a critic that he asked to be judged. IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

IN DRESDEN, a city renowned for the picture-perfect restoration by which it looks the same and yet entirely strange, an old tale of love and deception is playing out.

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease.

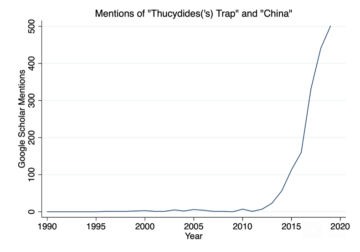

Tiny molecules came up big in 2021. By year’s end, COVID-19 vaccines based on snippets of mRNA, or messenger RNA, proved to be safe and incredibly effective at preventing the worst outcomes of the disease. When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as

When I discuss the US-China relationship with people, I’ve found that they often turn to the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” It seems as if few international relations books in the last decade have had as much influence as  William Hasselberger,

William Hasselberger,  IN SEPTEMBER, THE ADMINISTRATION

IN SEPTEMBER, THE ADMINISTRATION  The smooth, plastic egg fits in your palm. Brightly colored shell. Gray screen the size of a postage stamp. Below that, three buttons. Pull a thin plastic tab on the side, and the screen lights up. An 8-bit egg appears onscreen. It quivers and rolls and shakes until, finally, your Tamagotchi is born. Inside your head, the squishy, enigmatic organ known as the brain begins firing — not only to process the visual and sensory stimuli, but to generate curiosity in this new object. In fact, the spark of this fixation likely began before you even held this toy, when you heard friends feverishly speak about it and saw it in the clutches of popular kids at school.

The smooth, plastic egg fits in your palm. Brightly colored shell. Gray screen the size of a postage stamp. Below that, three buttons. Pull a thin plastic tab on the side, and the screen lights up. An 8-bit egg appears onscreen. It quivers and rolls and shakes until, finally, your Tamagotchi is born. Inside your head, the squishy, enigmatic organ known as the brain begins firing — not only to process the visual and sensory stimuli, but to generate curiosity in this new object. In fact, the spark of this fixation likely began before you even held this toy, when you heard friends feverishly speak about it and saw it in the clutches of popular kids at school.