by Eric Bies

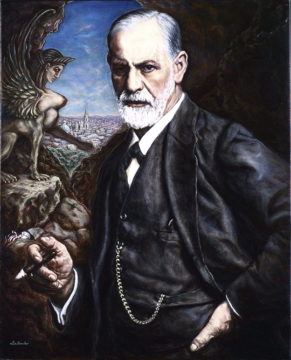

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

Thus we find the LORD, seated in his air-conditioned office, placing birds and beasts before toddling Adam, whose first instinct, amusingly, is to name. “Horse!” he yells, flailing his arms as the dapple-gray Arabian rounds a copse of palms. “Horse!” he yells again, though this time it’s a penguin sliding by on its belly.

Those who can read Hebrew tell us that adam simply means “man,” which means, for all intents and purposes, that God named the first person “Person.” Of all the uncollared dogs that showed up on the family farm in Michigan when my father was a boy—the dogs that arrived, rambled around, and were inevitably flattened on the interstate—each was known in the same fashion, without any fuss, simply as “Dog.”

Which makes one wonder, what animal was it that St. Francis of Assisi encountered on the forested slopes above Gubbio? It’s true that that particular story gets less airtime than those in which we find il Poverello preaching to the birds or kissing lepers. And yet it may just mark his greatest conversion: not from this or that religion to Catholic, or from Catholic to yet more Catholic, but from terrorizing wolf to adoring doggie. It isn’t hard to imagine Francis with a smile, allowing the bristling thing’s big paw to eclipse his palm as he takes it in his hand for a good shake, as if to say, “You have eaten some of these kind people and their pets, chewed on them and enjoyed it, and I love you still; go along now and be a new man.”

A well-known prayer, apocryphally attributed to Francis, tells us that it is by pardoning others that one is pardoned. And the notion that our inward state bears a direct relation to our outward action does sound right. But does the structure hold up analogically? Is it by harming that one is harmed? By helping that one is helped? By naming that one is named? Read more »

The first

The first

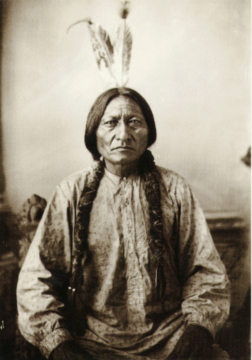

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.