by Tim Sommers

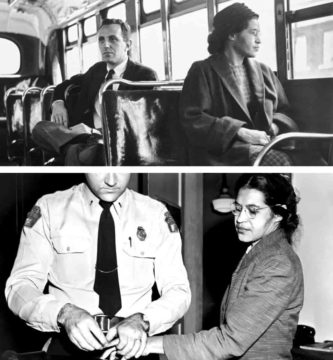

Judges judge. The way to tell that someone is a judge, as opposed to a legislator, is to examine whether the judge judges actual ongoing controversies between particular people who have incurred, or will incur, specific harms – or not. In that sense, the difference between legislating and judging is locus standi – or “standing.” Article III of the U.S. Constitution extends to the judicial branch of the US government only the power to decide “cases and controversies.” To seek a judicial remedy, one must demonstrate a sufficient connection to a harm to them personally that is a result of a law, or action, that is the subject of their case.

Civil Rights Activists were forced to commit civil disobedience, to openly break laws, and be punished for doing so, because “law testing” is (or, rather, was) not allowed. To have standing in cases where people of color were denied the right to be in certain spaces, someone of color had to go into and physically occupy those spaces, then face the legal, and often actual physical, peril that resulted. In other words, Civil Rights Activists were not allowed to challenge the Constitutionality of laws in an American court without standing. And they couldn’t get standing without breaking the (relevant) law.

But that’s all done with now. Now, you are free to pursue a case all the way up to the Supreme Court on the theory that hypothetically someone might one day break that law or merely disagree with it on policy or political grounds. This is what I mean by the death of standing. I’ll just give two examples from the last session of the Supreme Court. But there are other recent cases suggesting standing is no longer a thing. Read more »

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

The first

The first

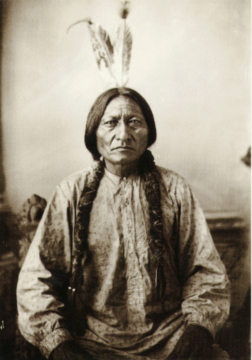

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.