by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

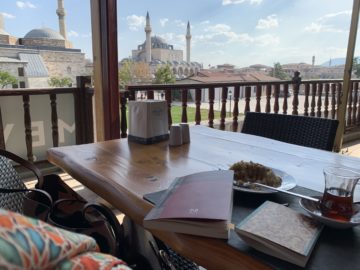

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

For once, I am letting the music of Rumi’s diction guide me: “khamush” (silent) and “khud” (self), a sonic coaxing of paradox, two words beginning with the same consonant, the first ending in “sh’, a sound that evokes the hushing of the ego’s voice, the softly-fading whisper of self-annihilation, the second ending as a sonic anchor in “ud,” suggesting the triumph of the self as it sheds worldly desires, alchemizing from base to the gold it was meant to be. This meditation yields the word “khuda” or “God,” who is paradoxically both “closer than the jugular vein” and a “hidden treasure,” in the words of the Qur’an, to be revealed actively, painstakingly in the hidden recesses of the self– as Rumi and the Sufi tradition teach. The divine resides in the self’s silences and music, solitude and communion, longing and ecstasy. Rumi’s path to love passes through such paradox; to be a Darwish, is to “linger by the door,” content to make a home of the beloved’s threshold where he gives himself up to gnosis through praise. Read more »

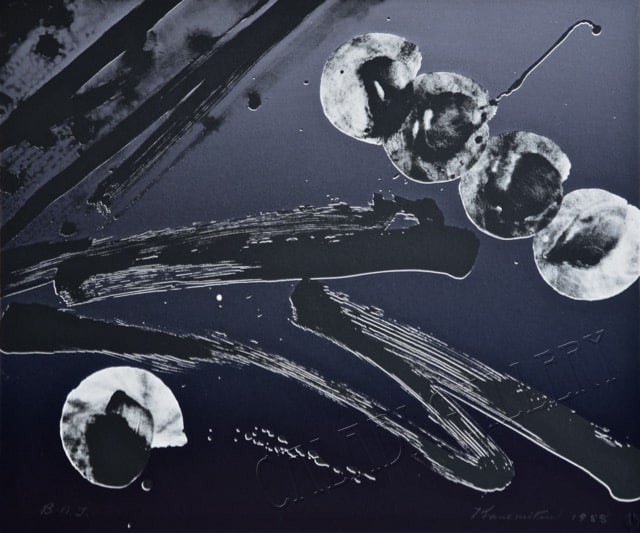

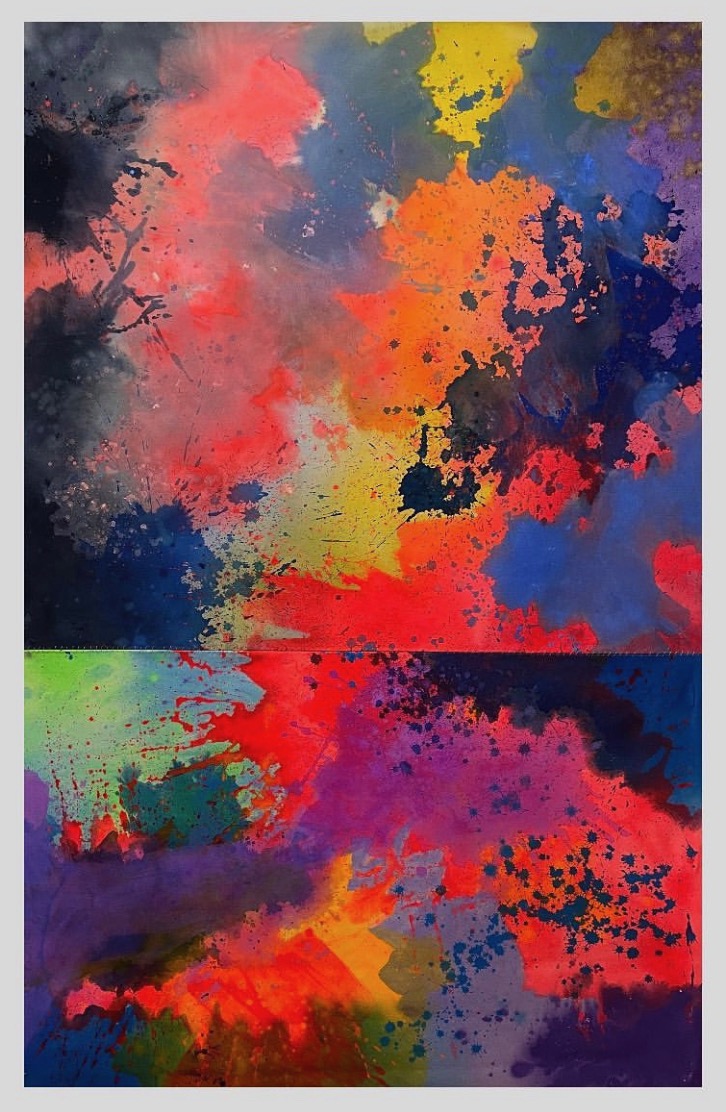

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988.

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988. “This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

“This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

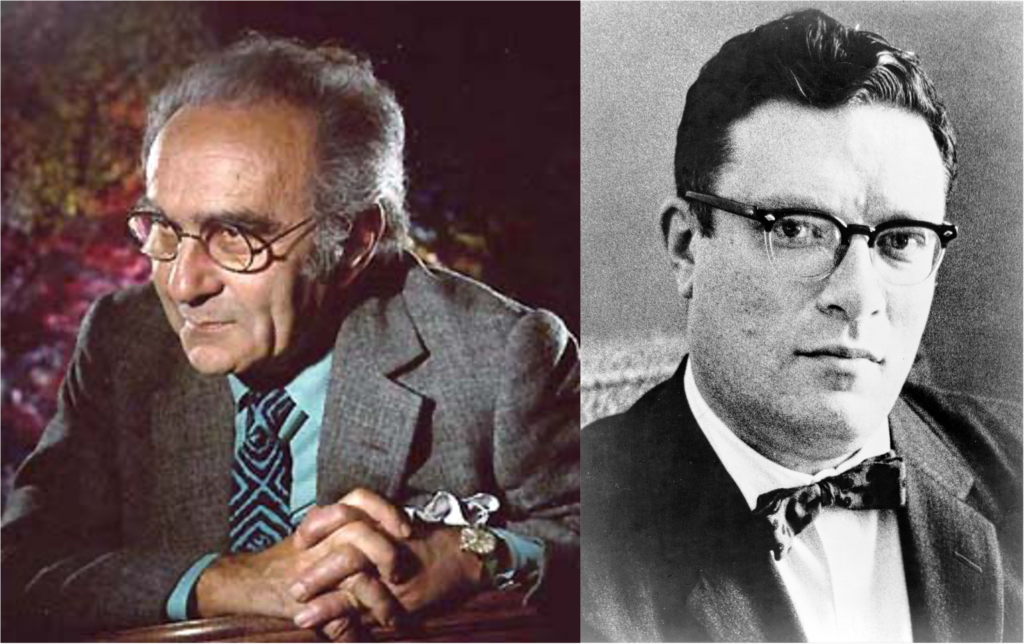

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Count Harry Kessler was born to write it all down. In this excerpt from his second ever diary entry, written at the German spa town of Bad Ems where Kaiser Wilhelm also summered, the 12-year-old French-born German boy has a high old time stretching the limits of the English language, in preparation for matriculation at a prestigious British boys’ school. An incipient snob and precociously intelligent, Kessler offers us a nutshell preview of the diabolical pleasure with which he will mash words, sounds and images for the next 57 years—savaging inanity wherever he sees it—but more importantly, promoting and nurturing great artists and thinkers along the way, including Rilke, Beckmann, Seurat, Grosz, Maillol, van der Velde, Max Reinhardt, Gordon Craig, von Hofmannsthal, Stravinsky, Rodin, Kurt Weill, Strauss, Nijinsky, Munch, Walther Rathenau and many others.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

Over the years I’ve been teaching, many people have asked me about the content of an elementary course I teach. I’m interested in the syllabi and exams of courses in other fields, so this I hope may be of interest to others as well. The survey course on which this exam is based is a smorgasbord of probability, voting theory, scaling, and other variable material. Since the class is very large, I often reluctantly make the final exam multiple choice as is the example below. Try it if you like. Two hours is all the time you have. Writing useful prompts for ChatGPT will take too long to be of much help.

In

In  Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.

Rashida Abuwala. Untitled Diptych, 2023.