by Paul Bloomfield

Marcus Aurelius wrote, “The best revenge is to not be like your enemy”. All ought to heed this wisdom: the right and the left, across classes, races, religions, and cultures, in personal life, politics, and war. Don’t be like the people you despise. Sounds easy, right?

One thing everyone has in common is that we all look down on our enemy: we think we are better than “them”. But if so, why do we so often see people react to their enemy by doing exactly what their enemy has done to them? Unsurprisingly, this is easiest to spot when others do it!

Examples are myriad. Counterexamples are rare: Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama. Perhaps the most ignored verse of the New Testament advises us to “turn the other cheek” when slapped by our enemy.

We (whoever the “we” are) have been dehumanized, disempowered, and oppressed by others. We have been treated in ways which are nakedly unjust and plain wrong. But as soon as we get sufficient power, once we get control, we go onto dehumanize, disempower, oppress those who have done so to us, convincing ourselves this is justice. It is all too easy to stoop to the level of our enemy.

If we defeat our enemy by acting like them, if they succeed in bringing us down to their level, then we have lost regardless of the outcome. Maybe we survive, but we survive through degradation: we become as bad as those we revile. We cut off our nose to spite our face.

For instance, humans often respond to their enemy’s anger with anger, when any fool can see that getting angry only makes everything worse for everyone. Who doesn’t say and do stupid things when angry? It is the nature of anger. But we do not learn. Read more »

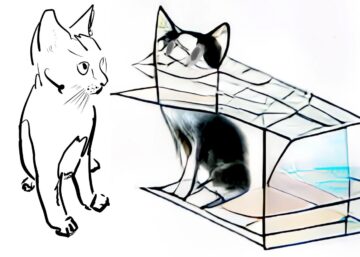

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

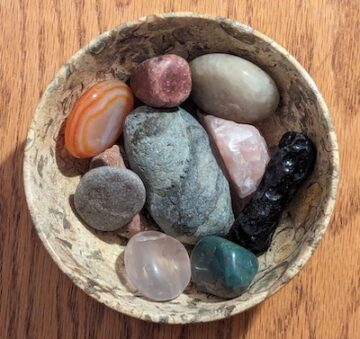

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made. I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

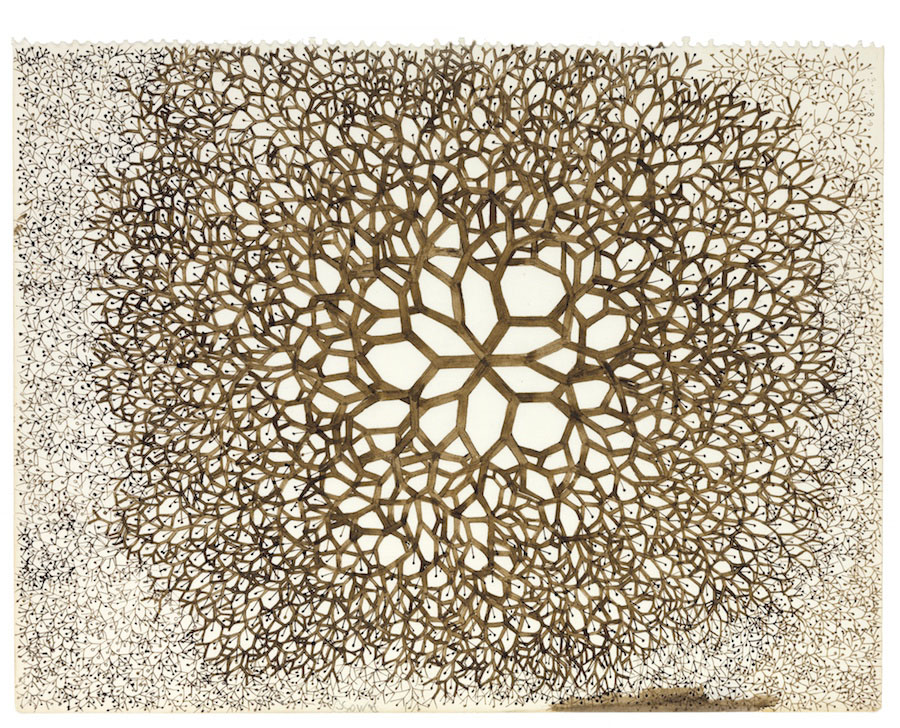

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones. Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

.

.

I simply can’t seem to stop writing the same essay over and over. This is, I admit, not a great opening to a new essay. If all I do is repeat myself, why bother reading something new from me? Fair enough. You’ve heard it all before. But allow me one objection, which is that many writers write the same novel repeatedly, many filmmakers create the same movie multiple times, and these are often the best novelists and filmmakers. Now, I don’t mean to put myself in this category, but I can take solace in the fact that the greats do the same thing I seem to be fated to do.

I simply can’t seem to stop writing the same essay over and over. This is, I admit, not a great opening to a new essay. If all I do is repeat myself, why bother reading something new from me? Fair enough. You’ve heard it all before. But allow me one objection, which is that many writers write the same novel repeatedly, many filmmakers create the same movie multiple times, and these are often the best novelists and filmmakers. Now, I don’t mean to put myself in this category, but I can take solace in the fact that the greats do the same thing I seem to be fated to do.