by David Oates

I was trying to get at something about living in the Pacific Northwest, something about the past and the future merging, blending. The way a forest can be that and can stand for that, both reality and symbol. A walk in deep woods, its distant past present as soil underfoot, as an actual springy feel, as redolence; its recent downfalls or hundred-year-old nurse logs killing and nurturing life on every side – like a metaphor for something. The cool uncanniness of time. Fear of the future. Ignorance of the past blended with selective recollection.

I wrote, “A thousand years from now, some timber-lame Charlemagne might make Portland his capital.” I played with that for a few sentences, and then asked: “And this imaginary king, this petty emperor – what will he remember of us?”

As I wrote the first line, I knew I was making trouble for us – for Juliane, my translator over in Heidelberg. And for Lotte, my Austrian friend, a Portlander who will struggle with me in the second stage, the “translation editing” wherein the Anglophone with his limited German asks the native speaker – a talented translator herself – about passages in Juliane’s proffered version. He asks if the German translation really gets it, captures it, in feel as well as in fact. Whether it has fun where I have had fun, or sets up paradox or complicated feeling where the English has done so.

After many decades of being a writer, it is working on translation this way that has taught me that feel counts as much as plot or evidence or logic or any of the other more linear dimensions of writing. That choosing tone and register, sometimes playing with contrast of high and low – these create the actual word-by-word experience of reading. The springy duff underfoot, the redolence, the emotion, the surprise. Step by step.

Humans are weird mixtures of nobility and baseness, and our daily experience is of starry-sky contemplations while the foot lands on a turd. And the art of translation shares this challenge with the art of writing: the challenge of capturing the full range. Of being true to the blending nuances, the irrational irreducibility. The laughable, unbearable feel of it. Of getting that texture into the text.

Indeed, it could be said that all writing is translation.

* * *

Lotte and I meet at a lakeside tavern in her neighborhood. We look out over the waters, shining in gray weather. Our tree-lined shores, crowded with houses. Our good beers standing before us. Our copies of Juliane’s translation on the table. We go to work on the trouble I’ve made: a first line that relies on puns and rhymes and chimes that cannot possibly be translated.

What’s a timber-lame Charlemagne? we wonder. I wrote it, and of course I know it doesn’t wholly make sense. It’s for fun! To kick things off with rakish liberty, with playfulness. It relies on the rhyme of Tamerlane and Charlemagne. And the ways our cut-down forests have lamed us – timber-lamed us – a crippling which will be felt by our descendants even unto the seventh, and seventieth, generations. Playful and despairing, serious and ridiculous. Untranslatable.

But in the German, Juliane has worked magic:

“In tausend Jahren könnte irgendein tumber Tamerlan Portland zu seiner Hauptstadt machen.”

She’s come up with a low-register word “tumber” that I recognize from the charming, slightly childish expression “tumber Tor” – meaning a dope, a silly guy, a bumpkin perhaps. Maybe dumbass. It gives us our rhymishness and our contrast of registers, low and then high.

And though it leaves out the timber part, yet it manages to echo it sonically (astonishing feat). I know enough to be happy that so much of the feel of the passage has been captured. When the translation gets the denotation right, and the register(s) right, and manages some of the connotation too – that’s when you declare victory and move on to the next puzzle.

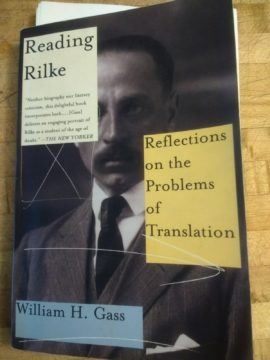

The poet William Gass, in his book Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, has commented that a line of poetry (and I would say, a line of any decent prose), is “a series of delicate adjudications, a peace created from contention.” And he asks,

The poet William Gass, in his book Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, has commented that a line of poetry (and I would say, a line of any decent prose), is “a series of delicate adjudications, a peace created from contention.” And he asks,

Must the translator mimic this mess, and take the measure of such miracles? He must.

(Or she must, we murmur.) Delicate adjudications: I love this phrase for the way it sums up the intimate struggle of writing, and of translating. In this book Gass offers countless examples of the tradeoffs typical of translation as he struggles with Rilke, trying to get the literal content right, and the right length or shortness, and the right gravity or sprightliness. Each of these making its separate demand and requiring solomonic judgments from the translator, word by word and line by line. What to sacrifice and what to promote.

* * *

Tone and register. My household gods.

Later in the same piece, aimed at a literate German-speaking audience, I’ll write:

“We know our time as grievously screwed up. But that won’t stop the future from nostalgizing over us. They will see only that there was a time before the whole world had been fucked.”

I’m acutely aware that “they” is not strictly correct – its antecedent is “the future” which is singular: an “it.” Yet when I wrote this passage, I made the choice based on register: “it” in this usage is more colloquial to American English. I wanted it to read breezily, easily – delivering dire reality with buoyant élan. I bit the bullet and there it is.

In fact the whole paragraph gets its energy from a combination of higher and lower diction (also called higher and lower “registers”). “Grievously” followed by “screwed” offers an abrupt descent from fancy talk to street talk. And the next two sentences do it again: from “nostalgizing” to “fucked,” dropping from the highfalutin Latin- (and Greek!-) based word to the ultimate vulgarism – the Anglo-Saxon crudity.

This contrast of Latinate and Germanic vocabulary is a neverending resource in English. For England’s late-medieval history of French in the court and Latin in the church and school – but Anglo-Saxon in the fields – has left its deep imprint not just in the meaning of words but in their human feel, their seethe and backspin. It seems half our vocabulary is invisibly marked for class this way, as if each word were secretly at Marxist dagger-points with its neighbors. . . yet maintaining a polite adjacency most of the time. Peasant words clomping into the palace. And fancy words, fey or earnest or over-complicated, gliding into the peasant’s hut, or bedroom, or fieldside celebration.

I like to use the word “range” for writing that moves fluently among registers. Moves boldly, often joyously. In American literary practice at least, moving confidently from higher diction suddenly into low – then back again – is a major marker of good style. And it is certainly one of the main distinctions between stuffy academic or bureaucratic prose, and literary prose. This ranginess is warrant of a lively mind, democratic and rowdy and open-armed.

It’s a kind of writing that can brave the hard things because it doesn’t pretend to speak as anything more than just another dopey-but-occasionally-right human. An Everyman, though that sounds a little stilted, pumped up with medieval allegory. So sometimes I see myself as everyboy, and that feels okay. With his best pal everygirl. Gettin’ into scrapes. I think I like this persona because my inner ten-year-old is very much still with me. I can like really simple things. But also be ready to be brave. If necessary. (If possible.) (There’s a statue in the Tuileries of a ten-year-old with his bare, meager, undefendable arms flung wide to protect his aged father from an unseen threat. We’re told he’s the young Spartacus. I like that.)

Halfway through the essay I wrote:

. . .we are beginning to borrow grief from the future. The best of us are, anyway – trying to feel it, trying to imagine the scale of loss and destruction we are unleashing. To feel it, we mourn as if already wounded. . . .We know that no private action can touch it, this future. No matter how thoughtful and ethical, no one person can stem this tide of six billion exhaust-belching humans. We are guilty personally, and by association, and collectively. . . .

This is proleptic grief – the future owned as a reality now, morally and emotionally now. There is no cure for this apparently inevitable future. No solace, no atonement, no forgiveness. Every mile we’ve driven has contributed. Every mile we’ve flown. Every fire we’ve burnt. Every burp and every fart.

That last paragraph sports a very fancy word known mostly to theologians – the Greek-based “proleptic” – the kind of word that practically drives readers away. But the paragraph’s last word is “fart.” My inner ten-year-old is satisfied. No one goes sprinting away. The human balance is restored , the ordinariness in which we live and joke and make even the most mortal moral decisions. That’s our range.

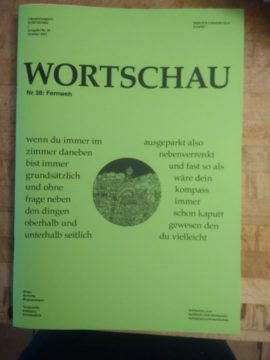

And did the translation capture it? Sometimes. Often! And I knew that once again I was blessed with good translators. I’ve been working with them over a span of seven years now, producing short incidental essays (in the form of letters) for the Düsseldorf literary journal Wortschau. I was invited there by the co-editor Johanna Hansen, a poet and painter of real talent. And generosity – offering me this forum, this audience I would never otherwise reach. She connected me with Juliane Gräbener-Müller, whose daily work is translating prominent English-language writers including best-sellers like Neal Stephenson. That she works so closely with me too – in my very low-profile life as a writer – is a joy and a startling privilege. And an ongoing opportunity to consider what really matters and what works in writing.

And did the translation capture it? Sometimes. Often! And I knew that once again I was blessed with good translators. I’ve been working with them over a span of seven years now, producing short incidental essays (in the form of letters) for the Düsseldorf literary journal Wortschau. I was invited there by the co-editor Johanna Hansen, a poet and painter of real talent. And generosity – offering me this forum, this audience I would never otherwise reach. She connected me with Juliane Gräbener-Müller, whose daily work is translating prominent English-language writers including best-sellers like Neal Stephenson. That she works so closely with me too – in my very low-profile life as a writer – is a joy and a startling privilege. And an ongoing opportunity to consider what really matters and what works in writing.

Thinking hard about the translation has had the effect of teaching me about writing itself: how much of it is a matter of feel and tone and register. I’m an old dog and I have been writing for more than five decades. I’m very glad still to be learning as I go, learning from translation.

* * *

“Translation” sounds like delivering a package in a faraway land. . . via some strange dissolving-and-reconstituting process, like being beamed up by the spaceship Enterprise. Exotic, not to say esoteric. Probably not something for the civilian to worry about. But the entire process of writing itself could be seen that way: as an excruciating transformation of that which has heretofore never been said into that which is, however imperfectly, given voice.

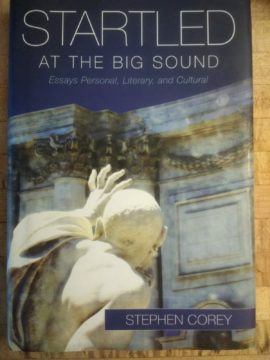

In the title essay of his book charmingly titled “Startled at the Big Sound,” the poet Stephen Corey (former editor of the literary journal Georgia Review) makes the case that all poetry is a kind of translation. He speaks of the “gap” a translator has to bridge, in delivering meaning from, say, Korean to English. Then he makes the intellectual leap: that in fact every poem has to re-create language in order to give expression, so that the result is effectively a new language.

In the title essay of his book charmingly titled “Startled at the Big Sound,” the poet Stephen Corey (former editor of the literary journal Georgia Review) makes the case that all poetry is a kind of translation. He speaks of the “gap” a translator has to bridge, in delivering meaning from, say, Korean to English. Then he makes the intellectual leap: that in fact every poem has to re-create language in order to give expression, so that the result is effectively a new language.

“I say here “Poetry is translation – which is to say that all poetry worth having and keeping achieves the status of a language substantially other than the speaker’s native tongue.”

The difficulty for the reader of such a language – and the pleasure as well – is that, like all things sui generis, it has no dictionary and or handbook of grammar and usage until the reader creates them with the help of the poems at hand. In this sense the reader is like an anthropologist doing field study of a newly discovered, isolated people and their unique system of speech.

You could say that everything in a poem is metaphorical, including intangibles like tone and voice: they all represent the poem’s certain way of looking at the world and the strange fact(s) of existence. They are that certain slant of light in which some things can be seen.

And what’s true of a good poem is true, I think, of good prose as well. When a novel begins “Call me Ishmael,” something uncanny is undertaken – word by word, a strange world unfolds. . . and it ain’t Kansas. An essay by Joan Didion or E.B. White, ditto. Emily Hiestand, David Foster Wallace. Montaigne. Bacon.

For a long time I have, somewhat vulgarly, described the mission of literature as the attempt “to f* the ineffable” – to say the unsayable (and the hell with decorum).

It’s a way of thinking about the strangeness of poetry, the alien quality of good prose. They are transforming because they have been transformed. You find your native speech, dear to you since early childhood – transmuted into the gold (or dross) of alien expression. Alien yet beautiful – like the surface of a new planet. Even the view from a dry cold moon, locked in its black-and-white austerity – can show us the color and pathos of our earth. Our little earth, soul of beauty. And (as we know) of perfidy.

I like thinking about novels and poems and (yes) essays as visitable planets, vehicles of wonder and danger, from which our own lives are briefly, strangely visible. Where an experienced world has been laboriously translated into some peculiar form of our home tongue, tasting oddly of all the same things we know here at home. . . but inflected with the pathos of distance. As if the gap from one person to another must be, after all, measured in light-years.

I have always found people to be at least this strange. Haven’t you?

* * *

When the American poet Marvin Bell came to offer a workshop at the little college where I taught, I sat in on it. He began with a kind of gruff realism I really appreciated – a voice aimed (I could tell) directly at the sort of sophomore poet who believes his or her floridly opaque effusions must be right because. . . something about how they actually felt this way. As if emotional sincerity were the beginning and ending of poetry.

On the chalkboard Bell drew a sort of wall. Stick figures: on one side the poet and on the other, the prospective reader. “Your goal is to get your words OVER this wall. To get them to connect with this stranger over here. Do you see? Someone who is not you, and who is NOT ALREADY INSIDE YOUR HEAD!” Then he sent little arrows arching up, up, and over. Some thumping straight into the wall, sticking or falling to the ground. In fact a little pile of them. (Teachers of creative writing classes will recognize this picture.)

Call it a wall. Call it a gap. A distance between self and others. Bridged, or surmounted, or not. You be the judge.

What the writer has felt or thought must be translated into some kind of common idiom. A sign-language if need be, like the famous one that various North-American indigenous peoples used with each other. Or a lingua franca, a third language shared by both parties. Perhaps not native tongue to either.

I like the strangeness this implies about writing. Specifically my writing. . . where I commit to various semaphores, and tactics, and metaphors (outlandish if necessary) to try to convey the sticky opaqueness, the brazen obliqueness, of the inner life. With the hope that somehow, you’ll recognize it. That your private inner country can hear news of mine.

Problems of translation. Every day. Every word.

* * *

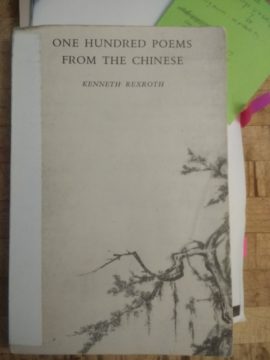

On my bookshelf are translations from translators who do not speak the original language. It seems odd, n’est-ce pas?

Yet how influential has been Kenneth Rexroth’s One Hundred Poems from the Chinese, published in 1971 by New Directions (trailing its clouds of glory from the many luminaries it had published). Rexroth chats with the reader in his introduction, mentioning how he comes at the task, how he has “taken note” of various scholarly translations, and how “Over the years. . . had many discussions of the poems and my translations with Chinese friends,” alas, “none of them specialists.” Rexroth pretends nothing here, and so we may take the book as it comes:

Yet how influential has been Kenneth Rexroth’s One Hundred Poems from the Chinese, published in 1971 by New Directions (trailing its clouds of glory from the many luminaries it had published). Rexroth chats with the reader in his introduction, mentioning how he comes at the task, how he has “taken note” of various scholarly translations, and how “Over the years. . . had many discussions of the poems and my translations with Chinese friends,” alas, “none of them specialists.” Rexroth pretends nothing here, and so we may take the book as it comes:

However, these translations are my own. In some cases they are very free, in others as exact as possible, depending on how I felt in relation to the particular poem at the time.

If my tone here seems rather flip (who am I to condescend to Rexroth?), I must report that few books of poetry have impacted my own writing more than this one. I have picked it up countless times to refresh my sense of these poets. I hear its voice, or voices, in my head surprisingly often. Sometimes I write imitations, trying to distance myself from our own time by becoming fiercely present to it, as Tu Fu or Su Tung P’o did.

I did eventually obtain other, more rigorous translations, some of them rather hoary like Arthur Walley’s, reeking of British Empire but splendid, and the later translations of Arthur Cooper. Yet I find myself turning oftenest to Rexroth.

I think also of the translation of the ancient Taoist classic Tao de Ching undertaken by the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin. Somehow this text seems even more daunting, I suppose because of its semi-scriptural aura. She too pretends to no scholarship in ancient Chinese. Yet when I drink there, I find refreshment and stillness and inspiration.

I think also of the translation of the ancient Taoist classic Tao de Ching undertaken by the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin. Somehow this text seems even more daunting, I suppose because of its semi-scriptural aura. She too pretends to no scholarship in ancient Chinese. Yet when I drink there, I find refreshment and stillness and inspiration.

What conclusion can this bring us to? Perhaps that translation is far more than any merely technical exercise. That the roots of syntax plunge deeper than any mere lexicon; which is perhaps to say that the meaning of meaning is as mysterious and inexhaustible as the human heart itself. A cat may look at a queen, and a beginner may be, sometimes, as close to the truth as anyone else.

* * *

Of beginners I think of two from the Old Testament who were, so says my King James Version, “translated” from their earthly lives directly into heaven – no stop-off at death. Elijah the prophet, in a whirlwind, but most famously Enoch, a so-called “Patriarch.” In the church of my youth it was explained to me that ancients like these lived so long – up to seven-hundred-plus years! – because the world was so much closer to its divine origins, and the heavenly essence was more potent and more present. This is an old theory that can be found in religions of many times and places. “In illo tempore” is the phrase summed up from many bodies of myth by scholar Mircea Eliade – “In those days”. . . things were better. It makes a kind of sense, but it creates a dispiriting time-line of ever-greater degeneracy. I suppose it could be a reassuring explanatory device when things seem to be going straight to hell around you. Depressingly reassuring?

Of course no historian can stand such bosh, since the misdeeds and calamities of the human condition are so clearly perennial. Few writings have helped me understand my own times more than those of the Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius. In them I see instantly that it is silly to be shocked by the viciousness and idiocy we see around us. There’s not a dime’s worth of difference, ancient or modern. Money talks, corruption is inevitable, and good people must make do in the chinks and bywaters and lucky pauses of the general shouting uproar. I have the Meditations in a fine old translation published by Oxford in 1944 from the scholar A.S.L. Farquharson. Think of bringing that out as the war raged on around you! (There may be Nazis in the hedgerows, but by God we’re going to carry on!) It seems like a parable itself – validation of the book’s philosophy of taking the long view with stoic calmness.

Of course no historian can stand such bosh, since the misdeeds and calamities of the human condition are so clearly perennial. Few writings have helped me understand my own times more than those of the Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius. In them I see instantly that it is silly to be shocked by the viciousness and idiocy we see around us. There’s not a dime’s worth of difference, ancient or modern. Money talks, corruption is inevitable, and good people must make do in the chinks and bywaters and lucky pauses of the general shouting uproar. I have the Meditations in a fine old translation published by Oxford in 1944 from the scholar A.S.L. Farquharson. Think of bringing that out as the war raged on around you! (There may be Nazis in the hedgerows, but by God we’re going to carry on!) It seems like a parable itself – validation of the book’s philosophy of taking the long view with stoic calmness.

Yet the idea of translation – of being transported out of your own times – seems compelling to me still. I’m no Enoch and I have no chance of being expedited to Paradise for my virtues. Yet – hasn’t Marcus Aurelius transported me, in some way? Delivered me from despondency? In almost exactly the same way Tu Fu has done.

They translated me into the mere truth of being human, caught in time, never to escape . . . until the final, permanent escape. This deliverance was translation back into my own times, into my own skin – not out and away from them. But by a circuitous route, a long circle back in time, via the written word, then plop straight back here, me in my same old life but different – deeper, calmer, and truer.

“Corruption never has been compulsory,” says the poet Robinson Jeffers – “when the cities lie at the monster’s feet there are left the mountains.” For me, such works as these are indeed mountains: I orient to them. And they send their healing waters to us always, their rivers coursing through the vilest times, and the best ones too. We have but to drink.

Note on Tamerlane illustration: Forensic facial reconstruction, from skull, by M. Gerasimov, 1941. Via Wikipedia.